HONDURAS

This is not a linear story with a simple path. This is a region with strong social movements relative to the rest of the world. Thus, it is a perfect illustration of the fact that Rising Up, Building Up, Standing Up, Shaking Up is not a perfect sequence. There are times when Rising Up becomes a vehicle for Building Up, and Standing Up a way to Build Up again.

Early in the story, a coup d’état changes everything. Many unexpected obstacles arise that demand changing in organization and tactics, and occasional retreats from action. Some strategies reach dead ends, while others open up new horizons for people-led change as unexpected political opportunities emerge. Throughout the story, Honduran women leaders from all walks of life become a vital political force in the construction of their futures and the defense of dignity in the midst of uncertainty and violence.

-

Situating this story

Honduras is among the most violent countries in the world. The country has a long history of militarism, stemming from the United States’ (U.S.) use of Honduras as a regional base of operations, and its deeply unequal society, shaped by class, gender and ethnicity. In the seventies and eighties, the U.S. government supported a series of authoritarian governments to repress revolutionary movements in the region and put down domestic opposition. State torture, assassination, disappearance, corruption and arbitrary detention in different periods led to fear and distrust in the government.

+ Read MoreIn the early 2000s, there was a period of relative openness and reform during which many social organizations worked to build democratic institutions and laws to protect rights and ensure access to justice. This imperfect democratic opening came to an abrupt halt with a coup d’état in 2009. Since then, corruption and violence have multiplied through the lethal combination of a corrupt and repressive state, the penetration of organized crime and drug trafficking, the expansion of privatized transnational projects, and a corrupt justice system. More than 90% of crimes go unpunished and one-third of Honduran territory has been granted in concessions to private companies for mining, hydroelectric plants, tourism and other megaprojects — without consultation or against the will of the indigenous and rural communities where they would be located. Violence against women in public and in private has reached alarming levels; between 2000 and 2018, 6,265 women were murdered, and three quarters of these were murdered since 2009. Despite the promise of economic development, Honduras ranks among the poorest and most inequitable countries in Latin America and the world.

In the midst of a human rights crisis, Hondurans from all walks of life are organizing and building movements to defend democracy and human rights, and demand justice. Women activists, defenders and feminists are at the center of these historic growing movements, defending their specific rights while defending the rights of others.

I believe that in the midst of all this despair, we need to nurture hope in ourselves as women, to believe that we are capable, that it’s possible to do something on behalf of our people. ~ Berta Cáceres, 2014

-

CHALLENGE

How to strengthen and connect women’s organizations in times of crisis?

In the 2000s in Honduras, as in the other Central American countries, women and their organizations faced rapid changes and uncertainty with the introduction of neoliberal privatization, austerity and free trade measures, and rollbacks in labor rights. These changes hit women especially hard and deepened economic inequality. The violent way in which they were imposed resulted in displacement and forced migration, often leaving women homeless and without support. A wave of land grabs threatened communities and sparked violent conflicts throughout the country. Meanwhile, rollbacks in rights (women’s, labor, land, indigenous rights, etc.) had stripped women of important tools to fight back. Efforts to build women’s movements and support feminist leadership in other movements suffered as activists tended to work on separate issues and mostly lacked a unifying analysis.

+ Read MoreFurthermore, in the aftermath of long years of armed conflict in the region, some Central American countries were experiencing a limited and incomplete peace process. Although Honduras did not experience an armed conflict as such, it had its own history of revolutionary groups that were violently suppressed, and over many years the country served as a platform for the United States' counterinsurgency policy in the region. The repression and the gradual loss of hope in the Central American democratic processes contributed to the apathy and inaction of society. Decades of struggle and repression had left women's movements fragmented, demobilized, and marginalized.

Women's and feminist organizations had to rethink their approach to advance towards equality, democracy, and peace.

Choice

Sparking political dialogue among women activists at the regional level to deepen the analysis and articulate the struggles.

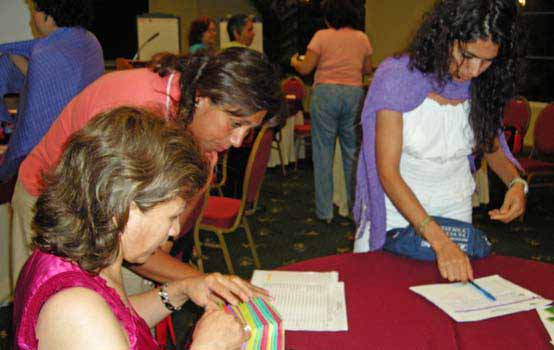

Based on its decades of experience in feminist popular education in the region and the solid alliances that had already been built, JASS began to work formally in the Mesoamerican region in 2006. That same year, in Panama JASS organized its first political dialogue, Movement Builders Institute, convening women activists to discuss what was happening across Mesoamerica, and explore how to revitalize women’s organizing in response to these challenges. We invited women activists from seven countries from the most important social movements in the region: urban and rural leaders, feminists, indigenous and campesino leaders, human rights defenders, trade unionists and teachers. To go beyond fragmentation and division, participants agreed to set aside their organizational hats, and put their minds and hearts together to analyze the context of crisis, build new relationships and visions, and identify shared strategies.

+ Read MoreThe question we asked ourselves was fundamental: What does it take to be able to imagine and build the women's movements of the future? The meeting produced a shared assessment of the impact of the political and economic changes we were facing, based on our personal and collective experiences. We affirmed that the region faced many common problems: the intensification of discrimination and violence against women, repression, inequality, conflict, militarism, and external intervention that hindered the development of independent agendas. This pioneering experience gave us an X-ray of the regional situation, strengthened networks, revitalized a sense of the possible, and led us to renew our commitment to building and strengthening movements. We decided to go back to basics: power analysis, community organizing, and developing agendas from below. This was the commitment that we took to Honduras.

Change

Reweaving regional women’s movements for action and creating rapid response tools

The energy of the Panama meeting gave birth to a new shared identity and informal regional alliance, Las Petateras, named for the weavers of the traditional palm mats from the region, petates. The name symbolizes the coming together of many diverse elements to form a flexible, yet unbreakable, bond—based on feminist solidarity, inclusion, reciprocity, and care—to rebuild and reorder a new social fabric torn by economic and political destruction. Las Petateras alliance included several Honduran women among its founders and functioned as a rapid response and solidarity network to bring feminist perspectives and women’s leadership to the forefront of key political moments in the region. Together we formulated a regional monitoring and mobilization strategy. In Honduras, sustained by an active virtual network, we galvanized direct action mobilizations, solidarity and strategic communications to amplify women’s voices on local, regional and global issues.

+ Read MoreFrom this articulation, the Feminist Transgression Watches emerged as a strategy to make visible our resistance and daily forms of civil disobedience at the national and international levels. This consisted of mobilizing solidarity at key moments, summoning observers, mobilizing resources, supporting strategies, and facilitating dissemination in the media and social networks, among other actions.

The Watches were activated by women and feminist groups at the country level, to mobilize solidarity to strengthen, publicize and protect our actions. Through them, we were able to mobilize financial and human resources and creative forms of direct action at crucial moments in the region. The Watches inspired the slogan adopted by women worldwide: Women Crossing the Line, and they denounced and underscored gender inequality and the differentiated impact of public policies. This helped to break down stereotypes about “women's issues” and incorporate them in broader political agendas.

+ Transcript/TranscripciónJASS held a meeting in 2006 with activists that came from different… all feminists, but very different expressions of feminism, different types of organizations and identities. At the meeting, we did a critical analysis of how all the work we’ve done—to build democratic institutions and legal frameworks and public policies to promote gender equality—was increasingly running up against changes occurring in [nation-] states, as they turn away from their human rights obligations and respond to the interests of large corporations, or to corporate power in dominant countries, by restricting rights, unleashing repression, and closing down spaces for dialogue between civil society and the government. We saw that women’s human rights were in danger of being seriously rolled back in several areas. With this thought in mind, at the meeting we said, "Well, we have to reorganize and strengthen solidarity among women in the Mesoamerican region, by learning what different women and organizations are doing within their countries."

The Observatories were a strategy to express and demonstrate regional solidarity with women and their movements at strategic moments, either at times of repression or violence, or when important matters were being decided for a country, for women, or for women’s rights; it also was important to make visible what women were contributing. ~ Marusia López Cruz, JASS

Caja de herramientas

-

CHALLENGE

Building deeper support for movement building

Our previous experiences and the expanding collaboration between feminists and women across various movements in Mesoamerica allowed us to be increasingly aware of the organizing efforts of indigenous and rural women, and the threats they face. These women are at the forefront of their communities’ struggles to defend land rights and the natural resources on which they depend for life. Their focus on protecting nature, rebuilding community and the rejection of extractive projects is vital to our feminist vision of the future.

+ Read MoreAs they courageously challenged the corrupt deals that lead to land grabs, and to the imposition of mining, monoculture, large tourism developments, and hydroelectric megaprojects that displace and destroy their communities, indigenous and rural women faced intensifying threats and risk. In the vast majority of cases, these projects were adopted without free, prior, and informed consent, as is mandated by law and ILO Convention 169. Large companies, backed up by armed private security, police and soldiers and often with the behind the scenes support of government elites, attacked grassroots organizations, intimidated women and their families, and tortured, imprisoned and assassinated activists. The media for its part, either failed to report these attacks or portrayed the defenders as the aggressors.

CHOICE

Developing an approach for working with indigenous and rural women, with communications as the starting point

Given this context, in 2008 JASS and the organizations and allies made a strategic decision to commit resources to more proactive movement building with rural and indigenous women leaders and activists in Honduras and the other countries of the region. We decided to promote and support processes to deepen knowledge, build women’s capacity with new concepts of leadership and power, and strengthen collective action in preparation for what looked to be an ever-more hostile organizing environment. Efforts were centered on strengthening the leadership of indigenous and rural women due to their strategic role, the degree of risk they faced and because they often lacked sufficient resources, opportunities, and support. We began by supporting their access to and use of communications tools.

+ Read MoreBuilding the capacity of indigenous and rural women

Building on the long-time relationship of key JASS women with indigenous people’s organizations in Honduras, we began a project to support indigenous and rural women’s access to and use of media on their own terms. There were very few stories of indigenous women in resistance in the media, and many of those that came out were distorted by sexism, racism, and the narrative of corporate interests, which described them as "backward", "anti progress”’ or even “terrorists”. Women did not have the training, tools, and access to media to counter this narrative and share their perspectives, so we started by building self-generated communications, using radio, social media, and Skype.

In 2010, together with Guatemalan partner Sinergia No’j, we gathered 35 indigenous and rural women from six countries for three intensely creative days of the first workshop, “Women Democratizing Media”. Participants included a communicator from Radio La Voz Lenca of the Civic Council of Popular and Indigenous Organizations of Honduras (COPINH), an organization with which JASS worked closely. In the workshop we conducted a critical analysis of stigmatizing media images and language and highlighted the importance of understanding communication as a right. Due to the success of the workshop and demand for media skills, these trainings continued for years, and formed the basis of JASS’ curriculum called “Women Crossing the Tech Line” used in different regions around the world.

CHANGE

Amplifying the voices of Honduran indigenous and rural women

In the workshops and through accompaniment, women learned to exercise and defend their right to communicate. The experiential training involved discussions and site visits with women's media projects and hands-on sessions on media production and other topics. Group members developed their own communications strategy to promote a feminist, indigenous agenda. They wrote press releases, scripts and produced a website and the video “Soy Mujer!”, recorded a radio spot, and created an on-going blog. During the training sessions, participants learned how to use media to organize virtually and reach out to a global audience.

+ Read MoreLater in workshops on community radio to mobilize against violence, participants experienced the tremendous power of radio—both as a communications tool and also as a bridge—enabling diverse women to speak and listen to one another’s stories and perspectives. The COPINH radio became a seed project in Honduras. The skills multiplied as women returned home to train other women and young people at home.

At the same time, JASS gained more insight into the challenges facing indigenous and rural women, and relationships with and among the women leaders and their organizations deepened. We continued to develop joint work with ally organizations, such as COPINH, as they developed content for community radio and independent communications networks as a vital form of education and mobilization.

+ Transcript/Transcripción

+ Transcript/TranscripciónAnd why with indigenous and rural women? I clearly remember a meeting in Costa Rica, because it was where we analyzed in greater depth the situation of women who were struggling for their territory and natural resources, something that hadn’t been thought about much at that time. There was also a very important gap in some contexts between feminists and indigenous and rural women in their struggles regarding their immediate demands, more closely linked to their most pressing needs. So at that point, we already saw ourselves as an organization that could bridge, that could contribute in some way to building bridges between organizations, but also at a level of knowledge. This was because, when we undertook that analysis, we also became aware (actually, we had seen it, but now with greater clarity), of the differentiated impact that all the repression and internalized oppression, etc. was having on indigenous and rural women in their struggle for territory.

In 2010, which was during the early years when JASS was also building its regional work, we decided to ally with Sinergia Noj, a Guatemalan organization that had already designed and carried out communication training, in order to jointly promote a regional communication training process with rural and indigenous women. Many of those participants are today working in communications with women human rights defenders’ networks or in other places. These were women with little or no experience in communications. The idea was to build their capacity, as communication is a central factor in women’s power and in making their strategies and voices visible. From these ten years of annual regional communication workshops, there were women who learned, for example, to conduct radio interviews and to draft public messages. Some of them replicated all or part of the workshops in their own organizations. They also met facilitators from the region to whom they could turn, and some of them did turn to these facilitators for support on specific topics. Due to this process – and in a few cases, their prior experience – some of the participants decided to concentrate on communications as their area of work in their organizations or movements. ~ Patricia Ardón

Caja de herramientas

-

CHALLENGE

How to respond to a political crisis? The 2009 coup d état

In the midst of building JASS work in Honduras, a shocking turn of events suddenly changed everything. In a military coup d’état in the early hours of June 28, 2009, the democratically elected president, Manuel Zelaya, was abducted and flown out of the country. Within hours, thousands of Hondurans, including many feminist activists, poured into the streets in shock and anger to condemn the coup and called for a return to democracy. The protest continued and grew in the days and weeks following the coup. Remarkably, and for the first time in Honduras’ political history, feminists— among them Petateras—visibly co-led a movement for democracy, demanding a return to the constitutional order.

+ Read MoreWe forged strategic alliances with a broad range of Honduran organizations, and several women emerged as trusted leaders within the resistance movement. We jointly adopted the name Feminists in Resistance, which rapidly became a force to be reckoned with, monitoring human rights violations and fighting to ensure that the feminist agenda remained central to the broader resistance. The Feminists in Resistance members stood out in the public actions in the streets. With their green banners, T-shirts, and hats, they formed a large green spot visible in the sea of protesters. Women of almost all ages participated, shouting: "No coups; no woman-beating!" (“¡Ni golpes de estado, ni golpes a las mujeres!”)

The coup regime unleashed a wave of brutal repression against La Resistencia, including gender violence against the women's movement. Without rule of law, human rights violations became daily occurrences, and violence and civil unrest led to a marked increase in verbal, physical and sexual assaults.

CHOICE

Led by feminists, women join as a pillar of resistance

For seven months, the Feminists in Resistance marched daily in the streets opposing the coup, while facing tear gas, truncheon blows, and bullets. The stakes couldn’t be higher. JASS, together with our allies, changed our strategy to prioritize solidarity and support for Feminists in Resistance and mobilize global actions to end the coup. We provided strategic support and resources through JASS’ global and broad solidarity networks to Honduran women activists to organize an agile and unconventional resistance strategy, with daily changes in plans and tactics.

+ Read More“Throughout this time, we feminists met after each demonstration to assess, because things changed from one day to the next. It was seven months, but it felt like seven years because everything was so different and each day was like a year of decisions, evaluations and strategy creation, and each day the strategy had to be changed." ~ Daysi Flores

Together with Feminist International Radio Endeavor (FIRE) and Las Petateras, we intensified our social media campaign to draw global attention to what was happening in Honduras, spotlighting women’s roles and demands in the resistance, and to denounce the human rights abuses and acts of repression. Advocacy and protests in collaboration with groups in Washington, D.C. targeted the U.S. Congress and State Department to suspend support of the coup government. Advocacy was also carried out with the Inter-American Human Rights Commission (IAHCR) to hold the line in not recognizing the regime. From throughout Honduras, with allies and networks of support from Latin America and around the world, we created a common front with many different human rights and social movements to demand a return to democracy and clear condemnation of the military coup.

To intensify international pressure further, in August 2009, JASS, FIRE, and Las Petateras organized a Feminist Resistance Watch and fact-finding mission of journalists and women leaders to Honduras. The group worked closely with Feminists in Resistance to document assassinations, rapes, beatings, and arbitrary detentions committed during the weeks that had elapsed since the coup d’état. The delegation documented a strong, bold. and inspiring feminist movement and took back a message of solidarity that asked for global support. JASS followed up by building international alliances, advocacy, and providing information on women’s role in the resistance.

CHANGE

Feminists from around the world join the struggle of Honduran women facing the democratic crisis

The solidarity work attracted the support of women from many countries to strengthen the extraordinary struggle of Honduran women for a return to democracy and an end to violence. The organization of an explicitly feminist force as part of the resistance, and the construction of solidarity ties helped maintain strength and courage.

+ Read MoreFeminists gained newfound respect in national politics at a critical moment. As part of the leadership of the National Popular Resistance Front, a mostly male-led body representing unions and various other social and community organizations, Feminists in Resistance worked to ensure that their demands were incorporated into the agenda and public message of the national resistance movement—not without constant pressure and occasional setbacks. Yet, in alliance with indigenous organizations, they managed to make the Front declare itself anti-patriarchal in its founding statutes. The rest of the world took note.

Although the coup regime remained in power, the message endured that feminist demands for equality, equity and emancipation form an indispensable part of the movements. The feminist leadership and international alliances forged in this period carried over as the movement looked ahead. This experience also shaped JASS’ own political priorities to focus increasingly on building cross-movement, cross-sectoral alliances where feminists and feminist agendas were central.

+ Transcript/TranscripciónAt first, we were all shocked because we had never imagined that a coup could happen. We had grown up in a democracy and -- for those of us who had fought for that – [a coup] was something that would send us into a retrogressive spiral, which it effectively did. We weren’t afraid, we knew that it was wrong – it was really a mix of things. So, we were shocked, but we were convinced that we had to go into the streets. And we did. It was truly instantaneous -- everyone was there. We started finding our friends there. There were young people, feminists, and union leaders – everyone was there amid the chaos. ~ Daysi Flores, JASS

Feministas en Resistencia (Feminists in Resistance) was a truly wonderful political experience that gratified us all. All the Honduran feminists came together to confront the coup, not only to respond to it, but also to position democratic values at the center, in the conviction that the construction of democracy is a political exercise of feminism. When we turned up as Feministas en Resistencia, even though we were few compared to the thousands and thousands of people who were demonstrating, they viewed us -- and we viewed ourselves -- in a significant way. We managed to position ourselves for the first time as part of the great Honduran people. In addition to positioning ourselves, we also gave visibility to important issues such as patriarchy and violence, even within movements. ~ Daysi Flores, JASS

Caja de herramientas

-

CHALLENGE

Sustaining mobilization faced with escalating violence

With the coup, the military moved into the streets to crackdown on citizen resistance with intimidation and attacks including rape, illegal detention and assassination. As the attacks on activists and their organizations escalated, we saw that women faced some of the most vicious and sexualized forms of violence. Reports showed an increase of at least 60 percent in the already-high rate of femicides since the coup. These attacks were afforded almost total impunity.

+ Read MoreThe presidential elections in November 2009, under the guise of returning the nation to civilian rule, eliminated the possibility of restoring constitutional order, and diminished international pressure to return to democracy. With democratic institutions shattered, a corrupt police state emerged that attacked from its position of power the advances the women’s movement had made. As the rule of law seemed to crumble, Honduras’ fragility created an easy opportunity for drug cartels. In this context, violence and threats to women increased dramatically. Daily demonstrations waned and fractures appeared within the resistance movement as members grapple with demoralization, fear, economic survival, and safety.

“The demonstrations ended because, in reality, each time there were fewer of us; because the repression became so harsh that it really broke the heart. We were afraid, I think fear had a lot to do with it.” ~ Daysi Flores, JASS

Grassroots organizations defending land and natural resources like the Civic Council of Popular and Indigenous Organizations of Honduras (COPINH), Black Fraternal Organization of Honduras of the Garifuna people (OFRANEH), Via Campesina and others came under repeated attack from the post-coup government as it moved quickly to concession and initiate new mega-projects, mining and logging. Farmers in the Bajo Aguan were targeted and many were killed by private security and police. Berta Cáceres led COPINH’s fight against the Agua Zarca dam, Miriam Miranda of OFRANEH led her people against militarization, drug trafficking and tourism development on the Atlantic coast. Police and soldiers, organized crime and private security thugs working for transnational companies involved in mining, hydroelectric dams, palm oil and other megaprojects joined forces against these and other people’s movements.

CHOICE

Documenting state violence and building networks for mutual protection

Despite this sharp spike in violence against women activists in Honduras, the media was silent on the subject. Even human rights organizations didn’t seem to grasp the specific threats to women activists.

+ Read MoreTo make these threats real and recognized, we decided that we must gather our own evidence and document this violence to provide an analysis of what was happening. JASS and its partners began working with regional women activists to conduct a study of violence against women activists in Mesoamerica. The findings, published in our first report in 2010, confirmed that “Violence has risen in every country in the region. The prevailing impunity and corruption, coupled with the region’s strongly macho (aggressive masculinity) culture, have favored the consolidation and entrenchment of a culture of violence against women.” It found that Honduran activists in the pro-democracy movement were at great risk, due to political repression, and that LGBTQI people and women activists participating in and leading the fight against “megaprojects” (dams, mines, land and water grabs for mono-cropping, etc.), were particularly targeted, attacked, killed and imprisoned. In conflicts over territory, their bodies became battlegrounds.

This unprecedented report also revealed that traditional human rights protection with its focus on the physical protection of the individual through personal security measures such as bodyguards and bullet-proof vests, did not meet the specific needs of women defenders and activists. In many cases, these measures separated the woman activist from her community and family, prevented her from continuing to organize and express her opinions, and failed to address her deeper physical and mental wellbeing. Furthermore, this approach to protection was not available to women, since it depended on the will of the State, and many women also faced violence in their homes and communities for their leadership and public roles. Our analysis concluded that women activists, and women human rights defenders (WHRDs), were coping with enormous risk and stress without sufficient support or mechanisms for protection and self-care.

CHANGE

Forming Regional and Honduran networks of women defenders and activists in Mesoamerica

Our research revealed the exacerbation of violence and the risks faced by women human rights defenders and activists. With our allies, we began to collectively visualize in-depth feminist approaches that enable and equip women to deal with the pain of living in violence and build a shared identity — a sense of belonging and trust that is vital to sustaining the hope and agility required to face their challenges.

+ Read MoreIn 2010, in a meeting called to present the report findings in Mexico, JASS – together with AWID, Consorcio-Oaxaca, Colectiva Feminista (from El Salvador) and UDEFEGUA (a human rights defenders’ network from Guatemala) – formed the regional Mesoamerican Initiative of Women Human Rights Defenders (IM-Defensoras), and were later joined by the Central American Women’s Fund. For the first time, we established a set of strategies for documenting and analyzing the forms of violence against women human rights defenders, and increased recognition of the problem and the need for gender-specific strategies among human rights actors and governments. Through national networks and protocols, we worked together to document cases, respond immediately to urgent cases, prevent and reduce risk, and build a shield of self-defense and support to sustain women defenders in the long term.

That same year, we founded the National Network of Women Human Rights Defenders of Honduras, a forum for Honduran women activists to share information about the crisis in the country, build a sisterhood across many differences and learn from the responses of other organizations to develop new ways to protect themselves. The National Network gradually formalized and supported women facing threats and attacks as they defended democracy, women’s and LGBTQI rights, and their land, territories and resources. The new national and regional networks sought to provide Honduran women with needed support and safety as threats against them mounted.

+ Transcript/Transcripción

+ Transcript/TranscripciónThe Mesoamerican Initiative began in 2010 after a regional meeting where we, women defenders and human-rights activists from different social movements, came together to share our views regarding the climate of violence, repression, and aggressions against women promoters of human rights in Mexico and Central America. Together we thought about existing alternatives for our protection and how we could build a more holistic and accompanied response, in a context of increasing violence in the region. We were in an environment where democratic spaces were closing, where actors, such as corporations or organized crime, were becoming more involved in aggressions against women activists, and where there was ongoing discrimination against activists because they are women, aggressions that occur in their own families and organizations, making the situation even more difficult. At that meeting, we realized that there was a very urgent need to build support networks, solidarity networks, and rapid-response networks among women, spaces of trust among women, in order to respond together when any compañera was threatened or assaulted. Networks in which the word, the needs, and the voices of women defenders would be given priority; this doesn’t always occur in spaces such as, for example, mixed movements, where aggressions or threats against male leaders are given visibility, but where everything women are experiencing is not acknowledged. Without us having foreseen it in the beginning, together with the organizations that we convened to that meeting in 2010 in Oaxaca, we saw how important it was to not only talk, but to begin creating alliances, synergies, linkages among women in different social movements, in order to think and act together in the face of violence against women defenders. These reflections gave birth to the Initiative, which focused on protection, not as a technical subject about security measures in the face of concrete threats or aggressions against specific persons. Rather, it was oriented towards building a social fabric of solidarity and effective response to aggressions that women experience, from a rationality of not just safeguarding lives and integrity, but also allowing our movements to continue to do their work, while women’s voices and needs were present throughout the protection process.

The most important outcome is the recognition that, while violence affects the entire populace, it affects women differently, and brings different consequences to us. This is the violence wielded not only by state entities, but also the consequences born, for example, by a housewife who decides to go out to protest because there has been a coup d'état – the consequences she faces for rebelling from her gender-assigned role. ~ Daysi Flores, JASS

Caja de herramientas

-

CHALLENGE

How to break the cycle when violence "normalizes", plunder intensifies, and resistance weakens?

At the same time that the Honduran women defenders strengthened their coordination and protection strategies, the adverse conditions for social organization continued to worsen. As the international community ended up recognizing the elections and the government of Porfirio Lobo, the call for a return to democracy lost traction. The decline in global attention encouraged the new regime, and the country's repression, violence, impunity, and violation of human rights became the norm.

+ Read MoreThis "normalization of violence" was hidden in the Honduran media, which downplayed human rights abuses and tried to convince the nation and the world that normality had returned to Honduras and the country was " open for business”. The constant government repression of the opposition weakened social movements and a large part of the international community, under strong pressure from the U.S. government, supported the Honduran government. This placed the resistance in a quandary, as it was divided between those who opted for a minimal relationship with the new government and those who refused to recognize it. The organizations suffered defections, divisions, repression, less external support, and declining morale.

At the same time, grassroots and women’s movements faced a growing imposition of extractive “mega-projects” on their territories, against which they organized to defend their lands and water, and protect their communities from displacement, environmental destruction, inequality, and intra-community conflicts. With huge profits at stake, state and corporate repression against people opposing these projects rose to alarming levels, including rape and sexual torture, kidnapping and assassination. After the adrenaline rush of the first weeks of the resistance, women and feminists sadly confronted the institutionalization of the post-coup government. The apparent triumph of injustice was a bitter pill to swallow, and Honduran activists, along with their supporters, faced crucial questions: How to sustain women activists and women’s organizations in the long term, and draw attention to the violence they face? How to make their struggle to create more bonds of solidarity with society more visible?

CHOICE

Better organize ourselves to challenge state violence and repression of movements

Faced with this, we identified the need to restore the balance between immediate responses to the crisis and long-term strategies. Quick response was necessary, but not sufficient to strengthen and protect women activists. More decentralized protection strategies were required. We begin to collectively envision a more deeply feminist movement approach to our WHRDs Networks. Our aim was to integrate the struggles in women’s personal lives for safety, equality and control of our bodies, with organizing, leadership and action in public arenas.

+ Read MoreWith the understanding that our power, well-being and security as women are essential, JASS, IM-Defensoras and the National Network of Honduras worked to create safe spaces for self-care and mutual support for women activists in risky and difficult contexts. Through the IM-Defensoras, we incorporated support for families, and created safe spaces to discuss and respond to specific, often sexualized, threats that women often don’t feel comfortable talking about in mixed groups. Questions were raised about the focus on WHRDs, the niche of the new networks, and the possible duplication of efforts, but we managed to incorporate the concepts and practices of self-care and wellness to deal with fear, trauma, and stigma. As one Honduran activist said, “Your body is political territory. It is one of the first spaces for constructing freedom…for defining how you exist as a woman, human being, and a citizen in this struggle.”

At the same time, we sought a strategy to break through the new repressive normality in the country and present the truth about violence and the courage of activists and women's movements. Together with the Nobel Women’s Initiative and regional allies, at the end of January 2012 we organized a delegation of women to Honduras, Guatemala and Mexico, led by Nobel Laureates Jody Williams and Rigoberta Menchú Tum. The purpose of the trip was to provide testimony and gather first-hand evidence of the impact that the escalation of violence had on women and girls in the region, to assess the role and response of governments, and to generate pressure from the media. Over the course of 10 days, we heard testimony from more than 200 women human rights defenders. Many took great risks traveling from different parts of the country to tell the stories of their struggles for the first time in an international forum. At the forum in Tegucigalpa, Berta Cáceres from COPINH offered one of the most powerful and emotional testimonies: "We cannot trust a public Ministry, a supreme court, a National Congress, the executive branch, the national police. We cannot, we have no one to trust. We can only have faith and hope in ourselves as the Honduran people."

CHANGE

Documenting and disseminating information on the human rights crisis in Honduras and expanding international advocacy work

The delegation’s high profile of leadership and visibility gave them the opportunity to meet with President Porfirio Lobo and high-ranking officials. That meeting sparked intense debates among women and men activists in Honduras about whether a meeting with the president meant recognition of the legitimacy of his government and a break with the political position of the resistance. Finally, the delegates of the Nobel Prize Women Initiative and JASS decided to meet with the president, together with other representatives of Feminists in Resistance, to present their approach directly to the executive branch. In a heated exchange, Honduran feminists lobbied for protection for women defenders, an end to impunity, a guarantee of reproductive rights, and an agreement to ratify the recognized United Nations protocol that allows activists to report government violations.

+ Read MoreThe delegation's visit to Honduras raised the public awareness of Honduran feminist organizations and made the urgency of the situation visible. We achieved extensive written, radio and television coverage. The delegation underscored the courageous work of COPINH and other grassroots organizations, and the specific threats directed at women leaders. We took reports with the findings of the visit to the US Congress and the Canadian Parliament, highlighting testimonies and evidence of repression and offering recommendations to address impunity and violence against activists. We developed a closer relationship with COPINH and other grassroots organizations made up of women and men who defended their lands and territory.

Despite this, a few months after the visit, the government imprisoned Berta Cáceres.

We participated in her defense and together with COPINH and other allies, we exerted national and international pressure and won her release. The influence of Berta as a feminist leader -- and of her organization COPINH -- grew among the movements that defend the land and territory, in defense of life, equality and the human rights of women in Honduras. Together with other people and organizations, the JASS team in Honduras played a direct role in protecting Berta and worked alongside her in many political actions. Berta clearly and publicly identified patriarchy as a central oppressive system of society, and COPINH -- with the support of JASS, among others -- developed anti-patriarchal training activities that continue to this day.

The strategy of creating networks of women defenders to further protect them and amplify their voices received international recognition - in 2014, the IM-Defenders received the Letelier-Moffitt Prize for Human Rights, which highlighted the fundamental role played by women human rights defenders in Mesoamerica. What was called a “holistic feminist protection approach”, developed by our IM-Defenders allies with ideas from many others around the world, has not only strengthened the networks of defenders and their members, but has also impacted the thinking and the practice of different organizations and foundations.

+ Transcript/TranscripciónThe national assessments were shared in each country by the organizations that had participated in Oaxaca. Concurrently – or later -- national networks, each with its own distinctive features, were established among the different initiatives in each country. These national networks arose from the clearly identified need to build a political fabric of local protection, that was familiar with and understood the context, the risks and the responses to risk that have enabled communities, organizations, peoples and movements to resist and sustain their struggles in the past and -- based on them – to think about new forms of protection. In Honduras, JASS and the CDM (Centro de Derechos de las Mujeres) undertook the process of sharing the assessment, and The Network was formed there in August 2010. The Network was coordinated by JASS and supported by its founders who took advantage of the gatherings of other organizations to meet as defenders in spaces of solidarity that allowed them to build La Red organically. At varying rhythms, in the different national networks we began a more precise registration process of the attacks to better understand how, where, and who perpetrated them and their specific impact on women. We created solidarity groups that were responsible for carrying out urgent actions and providing a rapid response to the aggressions suffered by the compañeras. At the same time, we learned to conduct risk analyses and prepare security plans that contemplated the specific needs of women. Response activities included international complaints, calls to generate political pressure on various decision makers when a compañera was criminalized, accompaniment for the temporary relocation of the defender and her family, accompaniment in the struggle, raising the profile of the defender or the fight itself, the promotion of awards, medical attention in the case of physical attacks, equipment to enhance physical security (cameras, fences, gates, etc.), solidarity accommodations, visits to accompany the struggles; and carrying out health care, collective care and healing activities. We were being born, learning together and organizing ourselves, in a way that was -- and continues to be -- our strength and our commitment. ~ Orfe Castillo

Holistic feminist protection is a way of looking at protection for women human rights defenders that recognizes the gendered needs that we have as defenders, while acknowledging that we don’t live in a different reality than other women, that we have double and triple shifts, that we are discriminated against in our organizational spaces, and on the street, and in our lives, and thus we require protection measures that not only come to our aid in an emergency or specific situation, but also give us the necessary power, resources, and leadership to be able to create safer environments for our protection. ~ Marusia López, JASS

Caja de herramientas

-

CHALLENGE

The murder of Berta Cáceres

Progress in the protection and visibility of women human rights defenders and social activists stalled when the new government of Juan Orlando Hernández (known in Honduras as JOH) was elected in November 2013. US government funding and political support continued despite the documentation of human rights violations and advocacy conducted in the US Congress. The renowned leadership of Berta Cáceres made her a target for repression and criminalization by government forces and transnational companies. Attacks and death threats against Berta and other women defenders grew frequent.

+ Read MoreIn 2015, popular protests against massive corruption scandals faced repression by the Hernandez government. At the same time, the constant mobilization from below opened up new opportunities to build women's leaderships and movements. Although Feminists in Resistance did not play the same leadership role that it had in the post-coup period, the women and feminists who participated in the resistance to the coup, together with young people who joined in this stage, were active in the mobilizations and helped to build international solidarity. The government's response was closure, increasingly authoritarian laws, and the criminalization of opposition leaders. Hernandez was clearly intent upon imposing his agenda of opening everything up to foreign investment and promoting extractive projects, regardless of the cost to his own people.

On April 22, 2015, Berta Cáceres received the Goldman Environmental Prize. In her speech, she spoke firmly about ending militarization, concessions and megaprojects that displace indigenous peoples, and described the struggle of indigenous defenders in Honduras: “We are the ancestral custodians, the Lenca people, protected by the spirits of the girls who teach us that giving our lives in multiple ways for the defense of rivers is giving our lives for the good of humanity and this planet." A year later, on March 2, 2016, Honduras was shaken by the murder of beloved leader Berta Cáceres at her home in La Esperanza, an attack in which Gustavo Castro, a Mexican defender and activist, was also seriously injured. Her murder sent a shock wave throughout the world where COPINH and Berta had forged multiple alliances. For JASS and hundreds more in Honduras and abroad, Berta was an example, inspiration, ally and close friend.

Berta's murder caused great pain in broad sectors of the population and also undercut many assumptions. Berta traveled around the world building solidarity and demanding respect for the rights of women and indigenous peoples and for environmental justice. Her high international profile convinced many that despite death threats, the government and other private sector actors would not dare to murder her due to the political cost of assassinating such a recognized defender. When she received the award, there was great tension in Honduras and several activists received threats, including the JASS staff. We knew that her visibility was critical to her cause, but could see how the interests against her reacted to her power as a leader and were sowing the seeds of division and conflict within communities.

CHOICE

“Berta did not die, she multiplied”: Transforming pain into popular mobilization

Despite the fact that Berta's murderers tried to paralyze social movements with her death, a few days after the murder, women, feminist leaders and other sectors joined to organize mobilizations in the streets of Honduras and the world. Confronted by Berta's murder, we deployed strong actions directed at 1) mobilization in the streets, 2) strengthening of global solidarity networks, 3) advocacy at the national and international level, 4) pressure in the media and 5) a legal campaign for justice. Popular organizations and human rights groups supported COPINH in the protests and demands for justice in La Esperanza and Tegucigalpa. COPINH reorganized its leadership to face the crisis and began to activate the relationships of solidarity that it had cultivated for years under Berta's leadership. Feelings of overwhelming sadness and defeat gave way to unprecedented national and international outrage, action, and support from a wide range of actors. Berta's daughters and the COPINH leadership spearheaded a phase of intense mobilization.

+ Read MoreWithin a week of her assassination, JASS pulled together a delegation to New York to advocate with the heads of state gathered at the United Nations Commission on the Status of Women (CSW). Supported by many allies and collaborating donors, the delegation was led by Berta’s daughter, Bertha Zúñiga Cáceres, and representatives from COPINH, the Defensoras network and JASS. The delegation gave interviews, participated in meetings with government representatives, and organized a gathering that drew more than 600 persons. The delegation culminated with a speech by young Bertha before the Plenary of the UN CSW calling for an independent investigation into her mother’s murder, and an immediate halt to the Gualcarque River dam project her mother worked so hard to stop. She also called for a review of all other infrastructure and development projects in the country to determine whether they complied with the requirement of “free, prior and informed consent” from indigenous peoples on their land as stated in ILO Convention 169. Her speech generated widespread media coverage and international attention. The visit connected Honduran activists and JASS with new allies.

JASS joined international allies, Washington DC-based justice groups, and women's human rights networks to demand justice and support Berta's demand to stop the dam project by directly lobbying international funding sources to withdraw from the Agua Zarca dam project. In addition, we started an advocacy campaign for the suspension of US aid and an information and mobilization campaign against the policies that permit or promote exploitation and extraction on indigenous lands. In all this work, women's organizations insisted that feminist values be remembered as an integral part of Berta's history of struggle and the vision of COPINH.

CHANGE

COPINH, with the support of JASS and many ally organizations around the world, makes headway in the struggle for truth and justice for Berta.

COPINH's fight for justice for Berta and the mobilization of international solidarity, resulted in two international investors, the Netherlands and Finland, ending their contractual relationships with the Agua Zarca dam project. The media strategy, research and advocacy work have kept pressure on the US and Honduran governments. In June 2016, a bill - H.R.5474 - Berta Caceres Human Rights in Honduras - to suspend security aid to Honduras until human rights violations have been addressed was introduced in the U.S. House of Representatives. JASS and our allies have continued to press for the passage of this initiative, and we have promoted actions in other countries to pressure the Honduran government to guarantee justice and respect human rights in the country.

+ Read MoreIn November 2018, the National Criminal Court of Honduras convicted seven perpetrators of Berta's murder and found that they had been hired by DESA executives. However, impunity in the case of Berta Cáceres continues. On various occasions, her family and COPINH have denounced irregularities in the judicial process, and the masterminds of the crime remain unpunished. Although charges were brought against the DESA manager, David Castillo, the proceedings were sluggish and only culminated in a sentence due to the insistence and pressure exerted by COPINH. After a trial characterized by constant delays, the DESA manager was found guilty as a co-perpetrator of the murder of Berta, marking a breakthrough in the fight for justice. COPINH’s main current demands are the punishment of the crime’s masterminds, the DESA company owners, and the liberation of the river for which Berta was fighting through the corruption case known as the Fraud on the Gualcarque River. As JASS, we have accompanied COPINH during the trials and contributed to the campaign for justice for Berta, strengthening communication work and participating in actions on the anniversaries of her murder.

Because Berta refused to be defined as just one thing—an environmentalist, a feminist, an indigenous rights activist—her life has become an inspiration to cross lines and link movements. The defense of land and territories and the movements against militarization, for women's rights, and to end the "war against drug trafficking" have been strengthened by the strategic decision to view Berta's death, despite the immense pain that it caused, as a moment to multiply her strength in the causes for which she fought. This is clearly reflected in the motto: “Berta did not die – she multiplied!”

+ Transcript/Transcripción

+ Transcript/TranscripciónThe conviction of David Castillo involved a lot of work. We have been dedicated to this struggle for five years and from the beginning – I think from the day following my mom’s murder -- we realized that this was an important matter that could signify a turning point in the search for justice. Five years later, the achievement of this conviction means, first of all, another step toward justice. I think this is also related to reparation and healing. The trial itself, the fact that we could be present as victims – even though this is something that was often denied us – was important to our healing. It is also important because this is what we had been saying since the very beginning, and I think that through this conviction the Honduran State acknowledges the truth of our words. That is important. Not only for me, as my mom’s daughter, but also for COPINH and the communities, it is important that the company’s general manger was found guilty. It was reparative, another step toward justice. What follows now is for the masterminds of the murder to be tried and punished, for the Gualcarque River concession to be rescinded, and for those persons who participated in ensuring that this criminal company could enter the Rio Blanco community and could act so violently against the communities and against my mom, to be brought to trial. That is one aspect of justice. The other aspect is related to the construction of memory, with how to build our story from our position, from our narrative, which is opposed to the criminalization of the persons who take up the fight to defend the territories, who often collide with this idea of development, of green capitalism. I think that this is also part of the construction of other narratives. It is this search for justice, for legal prosecution; it is that the banks that finance this project also face the consequences. Laura Zúñiga Cáceres

From the point of view of Berta’s friends and family, justice is profound: it is built by the peoples, in the communities, by moving forward in their projects to defend life and the future. It is also built by demanding that the justice institutions do their job. This construction isn’t easy in any of these spheres. Day after day, the communities face the negative impacts of the companies, the military and the police in the territories. And challenging the institutions of justice means appealing to racist and patriarchal spaces that have never contemplated the worldviews and realities of the communities and their leaders. ~ Laura Zuñiga, COPINH

Caja de herramientas

-

CHALLENGE

The rigged elections of 2017 and another wave of repression

In November 2017, the Honduran people were once again shaken when, through fraudulent elections, Juan Orlando Hernández was reelected as president of Honduras. Hernández got the courts to override the constitutional prohibition on reelection. Then the vote count on election night was plagued with irregularities and suspicions. The manipulation of the laws and democratic processes led the Honduran people to take to the streets and massively protest for several months, calling for the resignation of Hernandez and demonstrating electoral fraud. Young people who had voted against reelection for the first time staged these protests, which were met with violent repression that left several people dead, injured and detained.

+ Read MoreThe government of Juan Orlando Hernández has been characterized by repression against its own people, corruption, and links with drug trafficking. These factors, in addition to the high levels of violence in the country, have increased social discontent towards his government. In the same year of the fraudulent elections, Global Witness classified Honduras as one of the most dangerous countries in the world for land and environmental defenders. Since the 2009 coup, 123 activists have been murdered. Berta's murder revealed how far powerful interests will go to protect those interests, and since then many Honduran women activists fear for their lives.

In this context, and in the face of the acceleration in concessions of Honduran land and natural assets granted to national and international extractive companies (many of which operate fraudulently and illegally), social movements, women defenders, and activists faced the question: how to carry out long-term resistance?

CHOICE

Mapping the defense of land and territory and the role of women, and respond to new needs

We realized that we did not have in-depth knowledge of the situation faced by women defenders of land and territory throughout the country, so we decided to carry out a mapping of their organizational forms, their struggles, and their needs. The mapping gathered information on extractive projects and activities in the country and their devastating effects on the environment and peoples. It yielded important results regarding the differentiated impacts of extractivism on the lives of women. It also provided valuable information about women’s roles and their active, committed, and constant participation in the struggles for the defense of land, territory, and natural resources.

+ Read MoreIt further showed us that the integration of women in struggles is a source of empowerment and personal achievement, such as participation in community and political activities, an opportunity to train and learn, and having greater decision-making power in their families. It also showed that these achievements are not only individual but also organizational, since the contribution of women has made it possible to strengthen social organizations, reinforce alliance policies and open access to economic resources, which demonstrates the virtuous cycle that is generated when women participate fully.

The violence that women experience within their movements and social organizations, as well as within their families, also came to light. The mapping revealed how women defenders face specific gender-based violence, discrimination, and patriarchal barriers and practices within their own organizations. In addition, violence within families was identified as a constant in women's lives and is used as a control mechanism to dissuade them from actively participating in struggles and organizations. Although we had exposed these facts seeking a solution, we encountered resistance from some organizations and some male colleagues from mixed organizations. Faced with this, we conducted a feedback process with those organizations that were willing to receive it, although there were organizations that decided not to accept it. Carrying out the mapping gave us an idea of where we could channel our experience and optimize our impact to support women in building movements that defend the life and common goods of all.

A national school for women defenders of territory

From the mapping came the need to focus on strengthening the leadership of women defenders of land and territory and their capacities for analysis, organization, and strategy development. That need, combined with the extensive experience in feminist popular education developed at JASS through several decades of work in the region and continued in the Alquimia school, led us to adapt the regional leadership school to create a school specifically for Honduras. The curriculum and structure of the new school were designed and validated with the national defenders of land and territory through popular feminist education methodologies. Through negotiations with the National Autonomous University of Honduras (UNAH), it took the form of a diploma with a certificate from this university. The first class of the National School had 32 defenders from different territories nationwide.

Course accreditation was especially significant for participants who had not had prior access to formal education. Despite many obstacles, all but two participants completed the course. This experience highlighted the importance of training work and reaffirmed the need and the logic of continuing to implement the courses of the national Alquimia schools. However, it also revealed the multiple violence and threats that women face, both internally (in their organizations, movements, communities, and families) and externally (in their advocacy work), which affect their activism and their lives. It demonstrated that when women grow in their own leadership and power, there is also a violent reaction towards them, which is why it is essential to always have security and protection strategies for the return of the participants to their communities.

The findings of the mapping and of the first school showed that inequalities between men and women who participate in land and territory struggles persist in their organizations and movements. Therefore, articulating a Transformative Power and supporting women leaders in strengthening their leadership and in the eradication of patriarchal practices at a personal, family, organizational, and political level, became priority challenges. ~ JASS Mesoamerica

CHANGE

Knowledge is generated that is used to plan activities, to achieve changes in the discriminatory organizational culture, and to strengthen the leadership of women.

As one of the first studies on these issues in Honduras, the mapping has served as a consultation and reference tool not only for women defenders of territory but also for many organizations, including the United Nations. It demonstrates the scope and extent of extractive projects and activities in Honduras and reveals both the struggle of women against extractive companies and the specific violence that women experience in these contexts.

+ Read More“This mapping is like a mirror. I see a full reflection of my reality and the reality that my companions experience in their struggles. Sometimes I read it and I feel as if they had taken an X-ray of us.” ~ Wendy Cruz, La Via Campesina

From the mapping, many male leaders have begun to support or strengthen their support for women's leadership and have even encouraged women’s participation in the Alquimia National School in Honduras. Through the National School, we contribute to strengthening the strategic leadership, effectiveness, and resilience of women. They feel less alone, more confident and supported, both among themselves as indigenous and rural defenders and in their organizations. They are better prepared to face adverse contexts in their communities and organizations. We used different strategies and methodologies to strengthen collaboration, networking and the visibility of their agendas and their work.

As a result of the course, the participants have tools to analyze the context and the power dynamics in their territories. This allows them to strengthen their strategies and those of their movements and to share this knowledge with others to strengthen their leadership as women in their organizations. The leadership capacity of the participants has grown -- some have accepted national coordination positions within their organizations, others have taken charge of accompanying other struggles, and their level of leadership has increased notably.

“The change we observe throughout the training processes is clear: the motivation with which they arrived turns into creativity and their commitment into dreams and strategies to work together. Their comprehensive strengthening and empowerment is reflected just by noting the way they express it, with a strong and self-assured voice, speaking up during the plenary discussions. Their initial motivation and commitment are transformed into creativity, their dreams become desires to share experiences and strategies with other women with whom they share struggles. However, the changes resulting from the training processes are not immediate, they are gradual strengthening processes." ~ JASS Mesoamerica

Moving forward, the work of JASS in Honduras will continue to seek to strengthen and protect the collective power of Honduran women and their organizations defending their land, territory and common goods in order to build just and equal movements that contribute to de-patriarchalization, decolonization and decumulation of power and capital. Specifically, the work will be directed towards the strengthening of organizational and protection processes for defenders of various social movements through the courses and activities of the National Alquimia Schools. This will be combined with other popular feminist education processes, such as the "Live Schools" (“Escuelas Vivas”, communications activities tailored to respond to specific organizational needs), as well as self-care and solidarity actions with allies and other actors at the national and international level. We will also seek to facilitate collective advocacy processes that strengthen the collective power of movements while expanding the international human rights framework for women in Honduras.

+ Transcript/TranscripciónThe Feminist Alquimia School totally changed my life. When I first arrived, at the beginning, I did not know what it was all about. I was afraid – panicked -- to speak in public. Now I have learned how to speak in front of people. I have learned what my rights are, that I can be president, lead an entire country. [I’ve also learned] to handle problems within my organization, because problems always arise. [I’ve learned] to take care of myself, as well as to strengthen the network. ~ Belinda Vasquez

This diploma program has helped me a lot in all aspects of my life, mainly to find myself, to throw away all those burdens, to not carry a load that is not mine. Thanks to all the presenters. We learned from each of them, from their life experiences and from their experiences in female leadership training. Individually, I learned new techniques to ease my life; emotionally, [I learned] to love myself and to put many techniques into practice. And collectively, there with the women, sharing healing and how to cure pain. Organizationally it has mainly been that – the resolution of conflicts and misunderstandings. Day by day I put into practice some things that I learned through this process. The Feminist Alquimia (alchemy) diploma program turned out to be very important for me – it changed many aspects of my life. ~ Margarita Pineda, MILPAH

Caja de herramientas

-

Reflections

In the spirit of Berta Caceres, this is a story that captures many narratives. It is a story about Honduran women’s struggle both for their own rights and for justice for all Hondurans. It’s a story about women’s leadership in building broad social movements that bring together indigenous peoples, trade unionists, farmers, human rights activists and feminists. It’s a story about united citizen-led efforts for democracy and security in a context of deepening political crisis, violence and militarization. It is a story of local, regional and global mobilization against repression and corruption. And it’s a story of fear and hope, of great courage and great risk.

One of the great contributions is self-care – as a defender, positioning your body at the center of the debate. Your body is political territory and one of the first spaces for the construction of freedom... for defining how to exist as a woman, a human being, a citizen in this struggle. ~ Honduran activist

+ Transcript/TranscripciónFor us, self-care is fundamental because many of the dangerous situations that we defenders face have to do with discrimination and gender mandates. For example, defenders work in the midst of adverse conditions that cause greater risk as we carry out our work, such as, precisely what I said before, the double and triple work shifts, the enormous responsibility involved in caring for our kids, all the cultural baggage we have assimilated: our needs are unimportant, our health comes second, other people’s needs are always more important than our own, and all this creates conditions that wear us down and put us at higher risk. So self-care is a way for us to look at these needs, build wellbeing, and assimilate that we too, in our own lives, have to enjoy the rights that we struggle for and not feel guilty about it. We also have to realize that those movements that are concerned about the welfare of their people, their men and women, are movements that, first, do better work and, second, bring together more people who feel that these are spaces where one can truly live a different reality than the world of the rat race, exploitation, and violence. So, for us, no protection process or measures can be implemented without thinking about self-care. If you only place surveillance cameras and guards at the entrance to your organization and don’t work internally in the organization to pin down what is generating weariness and risk, then it’s quite likely that strict security measures will not be effective.

Alquimia (alchemy) is a meeting point where women from different organizations learn, build collective knowledge, and exchange experiences and strategies. Alquimia is a space not only for theoretical training, but also for the exchange of strategies for struggle, of experiences in resilience. It is a space where collective dreams are generated and also for learning -- by both those of us who participate as popular educators and the activists who attend these training processes. The Alquimia schools allow for the creation of new visions and new frameworks to interpret reality and to boost the quality of feminist analyzes based on transformative practice. ~ Mariela Arce, Feminist Popular Educator of Panama

+ Transcript/TranscripciónPolitical education and strengthening the leadership of women has always been at the center of JASS's work. In the case of Honduras, given the high levels of violence against women, for several years we focused on supporting the construction of the Red de Defensoras (Women Defenders’ Network). This coincided in timing and context with the emergence of the Mesoamerican Initiative of Women Human Rights Defenders (IMD). Over time we have decided to go back to basics, to go back to our beginning, by positioning feminist popular education at the core without neglecting to respond to situations of violence against women defenders, or referring them to the IMD, to the Red de Defensoras, or to other organizations that work more on emergency response. But in JASS, we decided to refocus our greatest efforts on strengthening leadership. We recognized that this is a medium to long-term wager, as structural violence is not going to disappear in the short term. We also recognized that we need the strong collective leadership of women to be able to create strategies, to build strategies to confront this structural violence, and formulate proposals, and that this involves strengthening the leadership of women in both women’s and mixed organizations. We are not going to fully see the impact of this for a few years. We do already see results, but not the global impact. We decided to join our efforts with others that are already being undertaken in Honduras [in leadership strengthening]. ~ Patricia Ardon

Berta was an extraordinary feminist, environmental activist, and indigenous leader among the Lenca people in Honduras. She was a brilliant organizer and strategist, a firm and inspiring teacher, and a true internationalist. Berta recognized how the Lenca communities’ struggle to protect their land and rivers was a global struggle, and at the same time she knew how to sow the love in her struggle in the heart of each person that she was involved with. (…) The power of her story, and the vast networks tied to her and COPINH unleashed an explosion of activism after her murder, mobilizing environmentalists, feminists, indigenous rights leaders, and human rights advocates around the world, who are still calling - in a loud collective voice today - for those responsible to be held accountable, and for an end to construction of dams and other projects that threaten people's lives. ~ Daysi Flores, JASS

+ Transcript/TranscripciónOne of the things is what my mom taught us. For me the most important thing is to rebel against death; it is rebellion. It is the refusal to accept that violence must immobilize us, or that fear should dissuade us from the conviction that justice is crucial for this country. The other thing that motivates us is love for our mother. It is the tremendous indignation and pain that this case gave us, and the need to prevent further repetition. This is difficult in this country, because every day we learn that another woman has been murdered, that the police are involved, and this fills us with outrage. I find that the murder of Keyla, who was a girl younger than me, who was about to graduate, and who was murdered by the police stirs up that indignation, that rage. It makes us see our bodies subjected to violence, and that is what we want to dismantle. That is what motivates us: dismantling the system of death in which we live in this country today. ~ Laura Zúñiga Cáceres

Our Mother Earth – militarized, fenced in, poisoned, a place where basic rights are systematically violated – demands that we take action. Let us build societies that are able to coexist in a fair, dignified way…in a way that protects life. Let us come together and remain hopeful as we defend and care for the blood of this earth and of her spirits. ~ Berta Cáceres

+ Transcript/TranscripciónIn our worldviews, we are beings who come from the earth, from the water, and from maize. The Lenca people are ancestral guardians of the rivers, in turn protected by the spirits of young girls, who teach us that giving our lives in various ways for the protection of the rivers is giving our lives for the well-being of humanity and of this planet. COPINH, walking alongside people struggling for their emancipation, validates this commitment to continue protecting our waters, the rivers, our shared resources and nature in general, as well as our rights as a people. Let us wake up! Let us wake up, humankind! We're out of time. We must shake our conscience free of the rapacious capitalism, racism and patriarchy that will only assure our self destruction. The Gualcarque River has called upon us, as have other gravely threatened rivers. We must answer their call. Our Mother Earth - militarized, fenced in, poisoned, a place where basic rights are systematically violated - demands that we take action. Let us build societies that are able to coexist in a fair, dignified way... in a way that protects life. Let us come together and remain hopeful as we defend and care for the blood of this earth and of her spirits. I dedicate this award to all the rebels out there, to my mother, to the Lenca people, to Rio Blanco and to the martyrs who gave their lives in the struggle to defend our natural resources. ~ Berta Cáceres

Back to Top

Archives

- Women and the Struggles for Land & Territory in Honduras (Part 1)

- Behind the Scenes of Extractives: Money, Power and Community Resistance Share This

- Power and Protection: Defending rights in hostile contexts

- Our Rights, Our Safety: Resources for Women Human Rights Defenders

- The Paths of Justice for Berta