Malawi

This is the story of how HIV-positive women across Malawi organized to make medicine and healthcare accessible for all HIV-positive people. It’s a story about women fighting stigma from the inside out—starting with their own feelings of shame and moving to take on discrimination in the society. It’s a story about how women living with HIV—and the inequality that breeds it—came to see that their day-to-day experience was precisely the expertise most needed by policymakers to find better solutions. It’s a story about women overcoming taboos and prejudice to talk about sex, care for their bodies in a new way, and help others do the same. It’s a story about marginalized women finding their voice; building connection and collective power; and using their anger, love, and determination to imagine alternatives, create a healthier life, and impact policy.

This is a story that proves that sustained organizing—the kind that develops women’s capacity and leadership, builds community and alliances (often with unlikely allies), and uses a combined strategy of participatory research, strategic communication, community organizing, and direct action—not only can change policy; it also will change hearts, minds, and lives.

-

CHALLENGE

Women’s Perspectives and Leadership Missing

In 2007, in the face of an AIDS pandemic, enormous amounts of money were being funneled into HIV/AIDS-related work in Malawi. Nonetheless, HIV infection rates were continuing to rise. And despite growing awareness of the impact on women—particularly poor and rural black women—women's voices and leadership were missing from the public discussion. There was no women-led agenda or movement-organizing by HIV-positive women. What was going on?

+ Read MoreOn the one hand, women's rights groups had been slow to prioritize HIV/AIDS, and on the other, most of the organized HIV/AIDS responses lacked a gender analysis. HIV-positive women were forming their own support groups but lacked ways to impact healthcare practices and influence policy. And even though women often made up a majority of members in the growing number of the HIV-positive organizations being created at this time, few held leadership positions.

JASS and our allies knew that HIV-positive women were surviving largely on their own initiative—with few resources and little recognition. Our question was how to support, strengthen, and accompany Malawian women in putting their voices, needs, and perspectives at the center of solutions. We wanted to do this in a way that would permanently transform their roles in their communities—and create a strong network for change that they could mobilize for any issues they faced.

CHOICE

Context and Relationships

As a movement builder and political facilitator, JASS focuses on enabling women to become leaders for change in their own contexts. In Malawi, this meant understanding what really was happening with HIV-positive women—both personally and in their communities—so we could best support their emerging voices and leadership.

To lay the groundwork, we pulled together an initial organizing team.

+ Read MoreIn addition to JASS staff, it included long-time regional facilitator Hope Chigidu; and two young women from a recent JASS Movement Builders School, Azola Goqwana and Sindi Blose, with experience as HIV organizers in South Africa. Together we began a process of inquiry and extensive outreach in the country. We deepened our knowledge of the context and the experiences of women through in-depth conversations with key players and women's organizations such as the Coalition of Women Living with HIV and AIDS (COWLHA) and Women for Fair Development (WOFAD). We visited support groups of women living positively, such as those organized by ActionAid and supported by the Open Society Initiative for Southern Africa (OSISA). We listened closely, learning what women cared deeply about, and where the needs and opportunities existed for movement building. This needs assessment process also enabled us to develop relationships, build trust, and identify individuals and organizations who were interested in participating in a women-led strategy.

CHANGE

Creating a Constituency

Our grassroots outreach strategy took us to rural areas to meet with HIV-positive women at support groups and in their homes, where we held small meetings and discussions. We learned the extent of women’s struggles and saw the effects of illness and poverty. Women struggled with inadequate food and healthcare; with insufficient treatment and inadequate health information. But on top of those most basic of needs, they also confronted stigma, domestic violence, abandonment, and social isolation.

+ Read MoreThe conversations confirmed our initial observations: HIV-positive women were marginalized in their homes and communities, as well as in the larger HIV/AIDS organizations. They were eager for structure and support to make their voices and needs heard among the nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and networks working on HIV/AIDS—let alone policy makers.

The research affirmed our decision to begin a focused movement-building strategy, using the extensive outreach as a natural entry point for organizing HIV-positive women. We knew this would be a difficult path, given the many challenges the women faced. But in our experience, there would be no sufficient change in the lives of HIV-positive women—or an adequate policy shift—unless women developed their own capacity to advocate for change, and impact the decisions and perceptions affecting their lives.

+ Transcript/Transcripción

+ Transcript/TranscripciónI want to go a little bit backwards, right, to talk about what was the importance and what was the idea behind movement-building, trying to mobilize women’s collective power not only in Malawi but in this particular region, in Southern Africa, where we sit. I think a few of us were born and raised here, our activism born here, we’re seeing the devastating impacts of HIV and AIDS in our own personal lives, in our families, in the communities where we came from. A lot of the responses that you were getting whether it was from governments or from NGOs, or from you know the UNs of this world, yes there was a full grounding of women’s experiences, yes there was an acknowledgement that women were the most “impacted” if you like, but there really wasn’t a deep enough analysis and understanding of why that was, and then that also led to strategies or interventions that were not really going to the heart of what it is that was driving HIV and AIDS to impact women in those particular ways. If I told what you were then seeing is that women were being mobilized mostly as what one would call “victims”, and not as agents of change, not as autonomous beings who could think, who could analyze, who could design their own strategies for change. A lot of the organizing that you were seeing was bringing women together to get you know services, which was a good thing right, services or largely to provide home-based care to other people, and not necessarily to other women. So some of us, we begin to ask those questions and then we begin to say ‘What are the different ways in which we can up the ante on women’s involvement, on women’s voice, on women’s leadership, but also on the issues that we care about as women?. And so that whole idea came together between you know colleagues in then the nascent JASS –I was in Action Aid then– and colleagues, including Sisonke Msimang who was in the Open Society Initiative for Southern Africa, you know put our heads together with some of the women living with HIV who had started some organizing in the region, the Coalition of Women Living with HIV and AIDS. And so together we came and started really analyzing those issues and sharing perspectives.

There were incredibly high levels of poverty and inequality. There were incredibly unsupported communities of women who were organising in interesting ways through community based structures but, were unsupported in terms of any kind of political vision or agenda. And there was a lot of passion and energy! There was also a lot of connection that started happening and this then was the genesis for the processes around convening of spaces for women activists from around the country as initial reflection-sharing and solidarity building spaces.

Shereen Essof, JASS Southern Africa

-

CHALLENGE

Getting Beneath the Surface

As we began bringing women together for workshops in various regions, to explore their experiences and build an initial foundation for our movement-building work, we encountered an unforeseen challenge. Amid an extensive NGO presence in Malawi at that time, many women had attended other NGO-sponsored workshops and had come to expect a certain type of interaction and the offer of material aid. Moreover, while women were clearly struggling with very deep challenges, they had become accustomed to expressing only the needs they thought appropriate to that NGO: “We need fertilizers,” they would say. Or: “We need alcohol and other sanitizers.”

+ Read MoreBut JASS wanted to change the “dependency” dynamic that international development NGOs were creating. Instead, we sought to foster an engaged community of women leading their own agenda. The familiar development pattern—in which women would receive assistance by playing their role as HIV-positive patients and asking for the “right thing”—didn’t encourage women to be fully themselves. In fact, it prevented them from experiencing a transformational process of discovery, affirmation, and power. We knew that we needed to create a different kind of gathering—one that could get below the surface-level of women’s needs, and address the structural systems of oppression and inequality that were limiting and sickening Malawian women.

CHOICE

Get-Togethers and Safe Space

To distinguish our gatherings from other NGO workshops, we renamed them "get-togethers" to suggest an informal, lively, and communal atmosphere. But we also wanted to create a different kind of experience—a sense of “safe space” in which the women would feel free to open up to one another about their lives.

+ Read MoreThe relaxed and reflective processes we held invited women to share their stories—to laugh and cry—and in the process, break the silence around taboo subjects and their own lived trauma. The sessions always included food, dancing, and songs. At the same time, they enabled the women to delve into conversation about the major issues impacting their lives, and how they were navigating the complex realities of gender, poverty, social isolation, and a lack of power in their communities. In the process, women found common ground with one another. They began to overcome internalized shame, and recognize their own dignity and “power within.”

CHANGE

Power Within

While JASS didn’t provide material support beyond small stipends as other NGOs did, we were offering something that women weren't getting anywhere else: a safe space where they could talk honestly about their lives, be part of an accepting community, and develop new kinds of personal and political awareness. Women discovered they had vital knowledge to share—about survival strategies, healthcare access, sex, and self-care. They came to realize that they weren't alone and they weren't to blame. In fact, they began to see themselves as resourceful, resilient survivors who deserved to thrive; to have a voice and be heard.

+ Read MoreNo matter how difficult women’s stories were, we made sure they didn't start or end in victimhood. Rather, we always explored the broader context of inequality, and the power dynamics in both the personal and public realms of their lives. As women reflected on their stories, we asked questions like: Who had power in the situation? What did that mean for you? Does this kind of thing happen to other women you know? Why? What do you think about it? Over time, these experiences nurtured a growth in confidence—the foundation of the women's "power within."

+ Transcript/Transcripción

+ Transcript/TranscripciónAs grassroots women, what we shared most in that meeting was about the violence which we face for those who have a husband. But for me by then it was the violence which we face in my community or even amongst my relatives, because by then when he was finding me it was like, my first husband passed away, I’ve been to my home now, and start being sick, and my brother would say ‘You know, this is what we’re not wanting to say, you should go to married, you see know you are just coming out with the disease, your husband is dead, who will take care of you?’ So it’s like, I was not having someone to support me or to take care of me the time of my sickness. And on the same, like how the community could look at you to say ‘There’s no way you can give her land, she’s already dead, what should we do with the land?’. So it’s like you are not recognized in the community as a person, and maybe some could not even come to your house as we live in a community to say ‘Hi’, or to say ‘Let’s have lunch together’. You can’t because always if you have lunch together, if we chat together, she will infect me.

The JASS feminist popular education starts with her story. Deep, personal gripping life stories, stories that take each woman to her cellar where demeaning stories buried in a box are shared. Each woman shines a light into all the corners of her body and the story is aired. Each story is carved in some power dynamics… be it the power a chief wields, power wielded by tradition and religion and hence internalized, power of a security guard at a local clinic who won’t let this woman go in to get her ARVs… Power, power, power… In sharing these stories, her body becomes a vehicle for learning to question different kinds of powers that society normally takes for granted, and with this understanding, her possibilities are released, blockages are cleared and she is able to break free of limits. Her inner knowing and personal shifts reverberate in the room and there is new energy. At this moment, there is some kind of relief as individually and collectively, the women cross a threshold; in their words, they cross many lines. They start getting empowered, advancing to another level of critical consciousness, and organizing. They become alive to the world around them.

Hope Chigudu, JASS Southern Africa

Caja de herramientas

-

CHALLENGE

Declining Health

By creating space for women to come together and share their experiences and pain, we were intentionally inviting them to put forward the realities of their whole lives. We knew that unleashing women’s power and agency depended on addressing this full range of issues that was impacting them. But those same harsh, day-to-day conditions created obstacles that made participating in workshops difficult. In their home communities, women were dealing with hunger, sickness, and poverty.

+ Read MoreThey had only inconsistent access to medication, and often lacked the food and water necessary to take it. Some women would arrive at workshops ill and malnourished, and at times fall asleep after eating. Sometimes women had to go to the hospital during a get-together. On occasion, women would pass their name tags to others, so they could share in the food and small allowances we provided. JASS facilitators had to grapple with how to address these tangible realities without being able to offer sustained material help. And we had to do it in a way that did not treat women as victims, but rather as potential leaders.

CHOICE

Body as Knowledge, Body as Entry Point for Organizing

JASS roots its movement building in a feminist popular education approach—drawing on life experiences and emotional realities as the raw material for analysis and strategy. So rather than ignore women's experiences of their bodies, we used the body as an entry point—as a source of knowledge and political analysis. Because it can be hard to share life experiences that involve blame, shame, or fear, we used Body Mapping as a central and ongoing tool for analysis and reflection.

+ Read MoreIn Body Mapping, women draw their bodies to explore how their life conditions and experiences have impacted them and are carried physically. They map where they hurt, where they have suffered, where they have experienced pleasure, pride, or happiness. This opens a conversation in which their bodies are not taboo, and their struggles aren’t due to personal misfortune. Rather, their bodies hold a vital history of their survival and resistance, knowledge and freedom. Body mapping in Malawi, something we returned to many times, allowed us to begin not with theoretical ideas, or by dispensing information, but through awareness of the body—layered with conversations; skits and stories; and the examination of patterns in their private lives, families, and communities.

CHANGE

Personal Is Political

Beginning with women’s own bodies as a source of knowledge was liberating. Women named and validated their own experiences of discrimination, trauma, violence, and survival. The process enabled them to release shame—they weren’t alone, others had similar experiences—and build trust in community with other women.

These body-centered strategies with HIV-positive women brought forth insights that have become the bedrock of JASS’ Heart-Mind-Body approach.

+ Read MoreOne that puts women’s lives and wellbeing at the center of movement building. In sharing secrets and stories, attending to our embodied selves, women not only discover commonalities with other women; they also make connections between their lived experiences and gender inequities and other social and political injustices. A transformation takes place as they build new understandings, and take note of their own survival, resilience, and knowledge—critical capacities for leadership and strategies for change. In these various ways, the gatherings validated and strengthened women’s existing abilities, and built a foundation of critical and political awareness for the movement-building work to come.

+ Transcript/TranscripciónSo what the most important part of JASS is, is not more of the same things which other organizations are doing, it has got different methodologies of interacting, engaging, equipping participants with the skill and knowledge, and the most important thing is it starts with you as an individual. While some organizations, if you are going for a meeting, that means you have a voice to report, to be accountable for. But most especially JASS and women activists is the changing of that person as a starting point. Then, if you are changed you also need to have others that can join you in that changing manner. Yes, I’ve been trained in women’s rights, I’ve been trained in gender, budget tracking and what, but the difference with the methodologies of JASS is you can work, but we work out there without considering yourself. So the most important which I like is the starting of you as a person, considering your body, considering your heart, considering your mind, it’s when you can go out. And that is a very critical way of rethinking again, because if it’s not your body, you can’t work, if it’s not your body you can’t do anything. So the starting of your body that’s the very most important thing. And the other thing is creating safe space and awareness of someone else, because in all the organizations it’s like you just wait to be accountable for someone else, and someone else is also accountable with a donor, so you just work according to report whether it is changing your or not, you need the report that the donor could be happy with it.

The name came from us women, because I think as a movement or I think as one of the methodologies that we use as JASS, I think we use the mind, heart and body. So we sat down and thought about what name could really suit this campaign, and we came up with the name 'Our Bodies Our Lives: the Fight for Better ARVs' because what we are fighting for is our own bodies and our own lives, and whatever we do when we meet in our trainings really speaks to what our bodies want or what our minds also want, so that's why the name is also, 'Our Bodies, Our Lives'.

Sibongile Singini, Woman Activist, JASS Southern Africa

Caja de herramientas

-

CHALLENGE

Understanding Power

Using feminist popular education we continued to deepen the conversations. We introduced political ideas and language to help sharpen analysis. In particular, JASS’ power framework—which exposes the multiple ways that power is used (its different “faces”) and the ways it impacts our lives, both positively and negatively—struck a chord. It gave women a language to express and validate what they had experienced.+ Read MoreThe idea of power within, which affirms women’s innate value and self-esteem, resonated deeply. Women also found the related concepts of power with and power to—ways of imagining their own capacity for resistance and for taking action with others—to be both empowering and provocative. The framework also enabled them to explicitly name the various types of power over—formal and informal forms of domination and control—that tried to keep them powerless.

Over time, 25 women emerged as leaders. They weren’t necessarily the ones who talked the most, or fit typical leadership profiles, but they showed a desire to get involved, develop skills and engage others. The challenge came as they grew in enthusiasm, and were eager to put the ideas they were learning into practice to make concrete change. And yet while JASS wanted to support women to take action, a shared organizing issue—a focus for change—had yet to surface.

CHOICE

Taking It Home

Many of the emerging leaders in our workshops were involved in networks of women living with HIV/AIDS. They often participated in support groups, and some had joined local committees. But they didn’t have a lot of organizing know-how, and very much wanted to gain more skills. Since a shared agenda had not yet emerged, we encouraged women to put their skills to work by defining individual projects in their home communities.

+ Read MoreIt was a way to strengthen their community leadership, address livelihood needs, and give women experience organizing. We helped women create what we called Personal Action Plans—goals and steps around a change project in their community.

During this first action phase, we provided close political accompaniment—supporting and visiting women in their home communities to understand their contexts, and offering skill-building workshops to help them implement their action plans. We incorporated training about the basics of organizing, including how to choose an issue with other women and how to formulate and present their demands to local decision makers.

CHANGE

Power To: Stories of Change

JASS stayed in close touch with the women and began to hear stories of how they successfully confronted powerful leaders in their communities or persuaded them to make changes. The projects were yielding results. One leader organized and trained 40 other women about land rights, and together they persuaded a village chief to allocate land parcels to them. Another helped secure two additional mobile health clinics to cover needy rural areas, with more clinics promised by Ministry of Health officials. A third built support to challenge the cultural practice of early marriage, a key risk factor for HIV.

+ Read MoreWith these actions came a sense of possibility and power to—women could see that they could have a voice, educate others, take action, and be courageous. They could make changes that not only helped themselves, but helped many others as well. JASS facilitated women in documenting their personal stories of change over this period of time, to both heighten their sense of accomplishment, and to enable other women to see what could be possible.

The relationships, leadership, and sense of community developed during this period served as a foundation for the movement building, mobilization, and campaigns to come.

+ Transcript/Transcripción

+ Transcript/TranscripciónThe language of power, for me to explain it to somebody else is that I would let that person know the power dynamics. Because they are categorised in two, three parts. The power within, that's the power within that person or within me; power to, power to do something; and also power over, for those who are in different authorities that have influence on other things like for example here in Malawi we had this problem of ARVs it was from the pharmaceuticals and how the ministry of health ordered legislation which caused deformities. So in order to explain to someone about power I would really elaborate and make that person understand what it means to have power within that person and power to do something that would bring change in that person.

I used my power within myself to challenge a village chief who had called me and other HIV positive women ‘walking corpses’ when we asked for fertilizers. After, he tested HIV positive, he needed my help so I told him I would help but there were conditions. He was to call a meeting, explain that when he refused to give us fertilizers, he did not know what he was doing and apologize to the women he called ‘walking corpses’. He would declare his status and persuade people to go for testing. Above all, he would find bags of fertilizers for the group. I wanted justice. Only after doing all that would he be allowed to join our group as the first man to do so.

Our Bodies Our Lives

Caja de herramientas

-

CHALLENGE

Conflict, Cohesion, and Collective Power

While the individual community projects gave women a sense of political purpose and newfound ability, they did not build collective power or "power with" others. Without collaboration among women, the possibilities and extent of change would be limited. During the time that women were off doing disparate projects, the incipient bonds created by the initial process also were weakening. Cracks and conflict began to emerge among women as our work progressed, particularly around issues of identity and difference.

+ Read MorePrejudices arose. For example, rumors about those believed to have engaged in sex work to survive ("bad women"), and those who had not ("good women"), threatened the cohesion of the group and reinforced shame, judgment, and oppressive social norms. This also threatened the possibility of the women coming together to create a larger change agenda, which was a central goal of JASS’ movement-building work in Malawi.

CHOICE

Power With: We Need Each Other To Make Change

The conflict presented an opportunity to further unpack the shaming social norms that women internalize and use against one another. By inviting deeper reflection about their experiences as women—about sexuality, control over women’s bodies, shame, violence, and poverty—we surfaced the ways that all women are forced to navigate power, sexuality, and survival.

+ Read MoreAmong the differences in the room, a common desire for change was also evident. This desire, and the recognition that “we need each other to make change,” laid the foundation for a more deeply felt unity. The experience sharpened the shared understanding of what HIV-positive women faced, and built a sense of collective strength—power with—the ability to work together to make change. The workshops during this period focused on developing leadership skills, including facilitation, conflict resolution, and working with allies.

CHANGE

Building Alliances

Through the trainings, women cultivated a sense of common purpose. But to take on a bigger collective agenda, they needed more political clout. So we built alliances. The first ones were with other women’s organizations: Coalition of Women Living with HIV and AIDS (COWLHA), Women for Fair Development (WOFAD), and Women’s Forum. Later—in a bold, but practical, strategic decision—we forged an unlikely partnership with an organization of HIV-positive religious leaders: the Malawi Network of Religious Leaders Living With HIV/AIDS (MANERELA+).

+ Read MoreMANERELA+ represented over 1,300 active members of churches and mosques across Malawi. Given that religious institutions had often perpetuated stigma, shame, and confusion about HIV/AIDS—especially by blaming “loose” women for the disease’s spread—this religious ally provided a crucial counterpoint. In addition to bringing the support of its vast constituency, we knew that MANERELA+ would bring visibility and legitimacy in different circles, including with the government; help secure resources; and add clout to the work led by HIV-positive women.

It took skilled negotiation and sustained work to build trust, create a shared feminist movement-building approach, and lay the groundwork for collaboration. The fact that a number of men in MANERELA+'s leadership were steeped in liberation theology and had a degree of feminist awareness, helped bridge the alliance between the groups. MANERELA+ proved to be a vital ally. As women's organizing aspirations grew, it brought a clear understanding of policy and politics, and played a key liaison role with the Health Ministry and other government offices, and the media.

+ Transcript/TranscripciónIn 2010 we received a pot of money to support work through an institutional partnership and JASS formed a partnership with an organisation called MANERELA+ which is the Malawi Network of Religious Leaders Living With HIV. And MANERELA+, particularly the executive director of MANERELA+ Rev Zembereka, had been a longtime friend and supporter of JASS from the time of the needs assessment days, so there was a relationship there. At that time too, women’s organisations in the country were weak, and so while JASS did do a scoping of possible women's rights organisations that they could partner with, they didn't fit the eligibility criteria, and so we ended up with MANERELA+ and that was a very definitive moment because JASS made a particular decision to partner with a male-led organisation, and that partnering came with a pot of money, at a moment in time when women had been part of JASS processes for almost 3 years, and who also needed the money. And so at that moment there was a real brokering that needed to happen between the women activist leaders who are now really like a core constituency of women, as well as now this new institutional partner, whom the women didn't really trust, and JASS. And much of 2011 was really around that brokering to ensure that we could pave the way for MANERELA+ to support a women-led movement building process, but that also communicated to the women that JASS held their interests at heart and uppermost in this process and so that was hard. I think the position that we took at that time was that once the negotiations and agreements were in place we just had to do it, and we had to prove in the doing it that we could maintain credibility and do what is that we say we were going to do.

During our discussion, sex workers were accused of being ‘bad women’ because they do not behave the way society expects ‘good women’ to. We paused and engaged in a conversation on what it really means to be a ‘good’ woman? How easy is it for any woman to live up to society’s expectations? Who has the power to set these expectations? Should women strive to meet these expectations, even when such beliefs are oppressive and limit them from realizing their full potential? How do sex workers perceive themselves? These are some of the questions that the participants sought to answer. We discussed the dangers of labelling ourselves and others. As participants explored the societal and internalized perceptions of what ‘good’ and ‘bad’ women are, they were able to identify the impact these labels have on them, as well as the ways they use these same perceptions to discriminate against others. We made it clear that if we continue to divide women into good and bad, we shall not be able to move together as women fighting for the same thing. A movement can’t be built on stereotypes.

Hope Chigudu, JASS Southern Africa

Caja de herramientas

-

CHALLENGE

No Unifying Organizing Issue

While work in individual communities had produced victories for those involved, no specific demand had emerged that could unite women, focus their efforts, and spark a movement. But women were ready for further action. At this point, JASS brought together the 25 now-core leaders for a process called the Women's Leadership Grounding Workshop, to discuss the next level of strategy and to see if we could arrive at a central demand to organize around.

+ Read MoreIn the discussions, women raised their usual concerns, such as poor access to treatment and lack of healthcare information. But no powerfully-felt, unifying theme emerged. Women needed experience engaging formal structures of power and decision-making, to make lasting change at a larger scale. Without such a galvanizing issue, the effort looked like it might stall.

CHOICE

From Problem to Organizing Issue

The facilitators decided to set up an intentionally relaxed and caring space one evening—a comfortable circle, candlelight, casual storytelling, song, a focus on self-care. Based on a body mapping activity we had done in the morning, we opened a conversation about where we felt the pain and injury of life’s blows—in our bodies, hearts, esteem. As women talked, cried, and laughed about their bodies and sex, long-suppressed anger and grief came forward—the shame, loneliness, and rejection; the loss of feeling attractive; the physical distortions that came with HIV treatment.

+ Read MoreThis moment of honesty and pain led to a breakthrough. Many women were struggling with body deformities, and as we dug deeper we realized that the source of the physical changes was not the illness of HIV, but rather toxic drugs. And further still, it came to light that although the World Health Organization no longer recommended the drugs, the Malawian government was still distributing them. This “aha!” moment defined our organizing agenda, and gave new and intense traction to our movement-building work.

CHANGE

A Campaign is Born

The single, galvanizing issue—toxic drugs—brought together so many elements of our work: It tapped into women’s anger over the government’s disregard for people, it generated a clear demand—modern drug treatment for HIV-positive people; and it activated women’s "power to" demand change. This was the spark for a focused organizing effort to win governmental responsiveness and accountability to women’s needs.

+ Read MoreThe core group of women leaders launched a campaign for access to treatment and modern antiretroviral (ARV) drugs, conducting what would come to be called “treatment literacy,” and organizing for improved drugs, treatment protocols, and health. The timing was auspicious: The newly-elected president, Joyce Banda, had long supported women’s rights and had expressed interest in HIV/AIDS treatment. Indeed, her election created a political opportunity to discuss and address issues such HIV/AIDS, and other social justice issues that had been actively repressed before.

+ Transcript/Transcripción

+ Transcript/TranscripciónThat experience really speaks to just how instrumental Malawi has been in helping JASS to articulate what we mean when we talk about Heart - Mind - Body, and what we mean when we talk about the importance of meeting women where they are and what's burning inside your gut, what is hurting inside your body and how that can then germinate a political issue around which women can organise because they feel it, they feel it in their bones, you know they feel it in their hearts, and I think it's still really powerful to read the stories that Hope generated from that process so when they're talking about what it means to be divorced from your husband because he thinks that you're ugly or what it means to not have access to seeds or land or whatever because you have visible deformities that make the Chief or whoever it is that has that power in your community withhold certain things that you need in order to sustain your life.

We started with a really powerful process of body mapping, where women spoke really intimately about their life journeys and their bodies and how it is that they carry differing manifestations of patriarchy on their body including, what it means to live positively. In these spaces we come together we share and we sit on the floor and over drinks and snacks we share stories of our lives and our coping strategies and often indigenous knowledge systems around what it means to live positively, sex and sexuality, the body etc. It was really in that process that we began to realize the power of the body deformities that women were experiencing. And so that became the very potent and pivotal moment that then allowed us to in some way turn a corner and escalate the movement building agenda in Malawi in a specific way.

Shereen Essof, JASS Southern Africa

Caja de herramientas

-

CHALLENGE

Need for Evidence

With an urgent demand in hand, we arrived at a new stage of work—and a new challenge. Based on their own experiences, women knew the older drugs were making them sick. But they needed evidence to support their claims and make a convincing public case, and they needed political visibility and power to be heard.

+ Read MoreBecause JASS was committed to a movement-building approach, we wanted to meet this challenge in a way that would not just yield data, but build people-power and community-based leadership. And this needed to be accomplished with limited resources.

CHOICE

Making the Case, Building Momentum

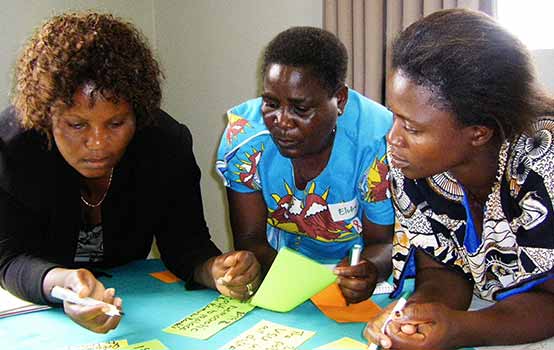

For JASS, the way to accomplish both things—gathering data across Malawi while building an active and expanded constituency—was to use a participatory research process lead by HIV-positive women themselves. At this time, the JASS team in Southern Africa had been growing to support the organizing, and brought new skills to implement this approach. Staff designed a process for training 60 women to gather data in their own communities. No one was sure how successful it would be. The results were amazing.

+ Read MoreThe 60 women, energized by both anger and hope for change, surveyed another 846 women across Malawi in just over two months. They reached out to their networks and support groups—gathering information, and inviting those surveyed to "join with us."

The data provided clear evidence that drug protocols and treatment access were adversely impacting women's lives, particularly in rural areas. They revealed that 70% of women living with HIV/AIDS in Malawi depended on the Stavudine-based treatment—the subpar drug still used in Malawi, that left them experiencing painful side effects including body deformities. Because of the easily-noticed body changes caused by these drugs, many of the women faced shaming, domestic violence, and social ostracism—leading them to stop treatment and endure poor health outcomes. When husbands or partners recognized the bodily changes or discovered their spouses were HIV-positive, they often unjustly blamed them for getting the disease.

There were other findings as well. Women could not consistently access drugs or receive appropriate treatment education because of insufficient locations and hours of clinic operation and frequent stock-outs of drugs. There were other social and political realities that also acted as deterrents to seeking treatment. In several cases, HIV-positive women waiting to be seen had to stand outside clinics in a queue, making their status publicly visible. In addition to subjecting them to social ostracism, this exposure of their status risked other repercussions, such as the denial of fertilizers or land-use to HIV-positive women.

CHANGE

Ready To Mobilize

The participatory research accomplished several things. Women gathered lots of data about HIV treatment experiences, information that was critical for supporting their demands. The data showed that the problems with the drugs were not just isolated or scattered events, but far-reaching, impacting huge numbers of women. The research revealed a policy problem at the Ministry of Health, which was not providing quality drugs and care to HIV-positive people in Malawi.

+ Read MoreBut the participatory research process also had enormous value for other movement-building goals. Women had taken on new public roles in conducting the survey and doing outreach; they and people around them began to see them as community leaders. And critically for the next stage of work, they had built a network of women around the country who were aware, outraged, and motivated on the issues—ready to be mobilized for change. The foundations for a campaign were in place—strong leaders, trusted allies, and a base of over 1200 women with whom they had connected through the research and other outreach.

+ Transcript/TranscripciónI think the key priority of that moment was to find a way to use the data that had been collected by women, in order to both build a case for a universal rollout of second line drugs, but also to begin to really demonstrate to women as part of a movement-building logic what is really possible if women come together and act collectively. So, with that thinking, it was really about looking at what the opportunities were on the ground and what it is we felt we needed to do specifically for campaign purposes and how it is that we could maximise our power basically, in order to drive the agenda. And so, it's a complex moment, because a number of things come together almost simultaneously, and I think it's difficult to pull out or separate one from the other because I think collectively they allowed us to build the momentum that ultimately led to the change. But there were obviously a series of you know interventions that at the beginning I guess we hadn’t anticipated at the beginning of the planning cycle, the opportune deep contextual possibilities as the plan unrolled to be able to further leverage and I think for me it's that, that's very interesting.

If you want to go and do strategic engagement to get the drug changed, you can’t just say what the problem is, you have to bring your evidence. So how were we going to collect evidence? This question led to the development of a participatory action research process, where we had 60 trained activist researchers. And so they went to their communities, and they used a survey that had been developed partly by me in conversation with the partners, and they collected 900 surveys.

Anna Davies-van Es, JASS Southern Africa

Caja de herramientas

-

CHALLENGE

Data + Demands + Energy = Taking it Public

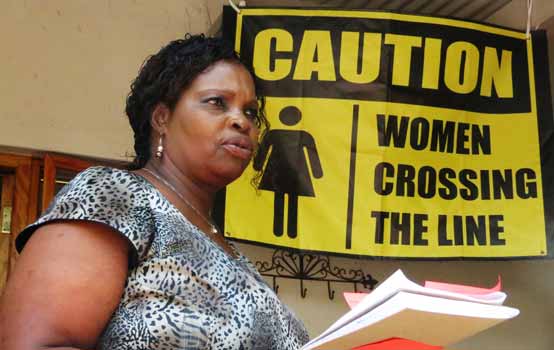

At this point, the work entered a new phase focused on impacting decision-makers and changing policy. Having completed and analyzed their research, women were full of passion and energy, and they knew a large number of people eager to be involved. The leaders now had clear evidence to support their demands for modern drug protocols. After the many years of deep and often slow movement-building work, it was time for women to use their collective power to gain a government response. It was time to take action and bring about real change.And so JASS launched the Our Bodies, Our Lives (OBOL) campaign for better antiretroviral (ARV) drugs.

+ Read MoreThe campaign gave the organizing a unified focus and made the demands visible.

The key challenge was how to strategically position community-based women leaders for maximum visibility and impact. After all, HIV-positive women were a generally marginalized group, even within HIV/AIDS advocacy. We wanted to shift the public debate and change the Ministry of Health’s policies—all without many resources. At this key moment, the partnership with the Malawi Network of Religious Leaders Living With HIV/AIDS (MANERELA+)—the well-connected coalition of religious leaders—proved valuable for helping OBOL achieve visibility and gain the ear of government officials.

CHOICE

Seizing Opportunity, Shaping Demands

Identifying and seizing political opportunity became critical in making our voices heard and impacting decision-makers. The national SAVE meeting, an HIV/AIDS advocacy conference, provided just such an opportunity for the Our Bodies, Our Lives campaign (OBOL). JASS and the campaign leaders knew the event would attract national attention and involve important players in the government, including officials in the Ministry of Health. So we decided to “piggy back” on it. We added our own gathering, a teach-in for women leaders from across Malawi, A National Women’s Dialogue, both to prepare for engaging the Ministry of Health and to celebrate the organizing to date.

+ Read MoreOn the day of the event, over 120 women showed up—twice as many as expected. Rather than conduct a workshop, we shifted into rally mode—using powerful speakers and dialogue to help women prepare to share stories and provide evidence of the devastating impact of Stavudine on their bodies and lives. We used the space, and the energy created by the dialogue, to formulate clear demands. They included a call for the immediate transition to quality antiretroviral (ARV) drugs for all women, and scaled-up treatment access and education.

When the head of the HIV unit arrived, ready to deliver his presentation on the ARV regimen in Malawi, he was greeted by a group of powerful and prepared women with their own agenda. They told him, “We want you to come into the circle and we want you to talk with us.” And they asked him, "Why don't we have access to quality ARVs with fewer side effects?" In this key moment, the women claimed their voice and power, creating a two-way knowledge exchange and demanding responsiveness to their needs.

CHANGE

Navigating Challenges, Holding Our Space

Women’s strong organized presence at the SAVE conference did not go unnoticed. It generated tension, and required fast-moving, strategic decision-making. The ability to respond to these unexpected challenges with clarity and fluidity was possible because of the high degree of preparation, organizing, and strong relationships, both within the campaign and with the Malawi Network of Religious Leaders Living With HIV/AIDS (MANERELA+) and other institutional allies.

As women of Our Bodies, Our Lives campaign (OBOL) prepared for the National Dialogue, we noticed a political nervousness and sense of tension about our presence.

+ Read MoreWe were acutely aware that the process could potentially expose an already-vulnerable group of women to political reprisal. The relationship with MANERELA+ proved vital at this key moment. Because of their networks and connections, they could use an “inside” political strategy—reassuring key authorities—so we could go ahead and hold the gathering and related activities productively and safely.

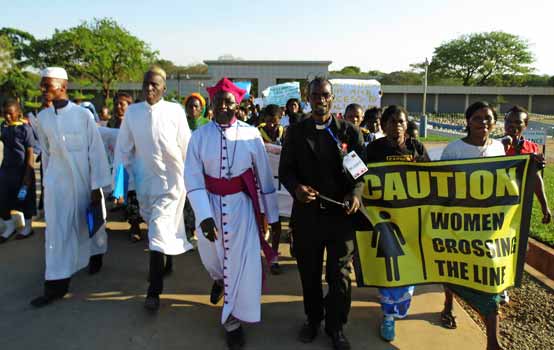

At another moment, we were able to navigate a difficult strategic choice. The Dialogue spanned a weekend, and OBOL and MANERELA+ had planned to include a religious service. When we learned that SAVE had also planned one, we struggled with whether it was more strategic to join theirs. In the end, women felt strongly that they needed their own service—both in order to reflect their religious diversity (Muslim and Christian) and so that women would play the leadership role. And so the women, MANERELA+, and the service committee led a powerful three-hour service that deeply conveyed the solidarity, community, and love at the heart of OBOL.

+ Transcript/Transcripción

+ Transcript/TranscripciónWe felt that it was a strategic opportunity, because there was energy, there was passion and there was a set of demands that now sat on a base of information that women had generated from the regions. So how do you put that together in a way that can really deliver on all of the objectives that we were needing to deliver on? And so what then emerged was the need to have something that eventually got called a National Dialogue. And this National Dialogue would bring together, in its initial iteration, it would bring together about 60 women for kind of a learning; a learning and analysis. So let's look at the research. What is it saying? And let's prepare for an engagement with the Ministry of Health. But in order to do that what are the other pieces that we may need? And so we identified a number of resource persons to come in as part of that learning preparation for engagement with the Ministry around the rights of HIV+ women and the broader civil society organizing landscape as well as some quite deep HIV/AIDS women's health, women's bodies related information so that when the officials from the Ministry came into the space we were prepared and had an agenda. Of course things never work out the way you plan. And so while we had designed an entire process, that was about the launch of the campaign and then this National Dialogue that had you know a kind of teach in section and then a public engagement section, we arrived in Malawi and I suddenly became aware that we were going to have over 120 people in this process. And so immediately my take was: "This is not a workshop anymore. This is a rally." And we've got to ride on the energy and excitement that women bring, in order to do what it is that we needed to do, but not in a kind of workshop mode, in a rally mode, you know? And so that's what happened. We really activated the energy and the drive that was in the room, to prepare and then engage the Ministry.

One of the really powerful moments for me at that Dialogue was seeing women talking to a representative of the Ministry of Health, Dr. Chimboandura, who had come into this space and had had a very sort of professional slideshow to tell women about what the coverage of treatment was and what the big plan was, and then women stood up and challenged him. And he was standing in the middle of the room, and had all of these women surrounding him, listening to him intently, and then telling him why XYZ of what he had said was not true in their constituencies, and how the government needed to do something, how the Ministry of Health needed to address that.

Maggie Mapondera, JASS

Caja de herramientas

-

CHALLENGE

Getting Our Demands In Front of Decision Makers

We were well positioned at this point, but still needed to get our demands in front of decision-makers. This called for a savvy communications strategy and strategic use of public spaces. We had learned that the new president and the Ministry of Health were now supporting a gradual phase out of Stavadine. This was certainly progress. But it was also highly problematic, as it would mean continued suffering for many poor HIV-positive women still receiving the old antiretroviral (ARV) drugs. Central to our demands was an immediate switch to the modern drugs.

+ Read MoreWe had already created key moments of visibility for this demand. Some weeks earlier, the Malawi Network of Religious Leaders Living With HIV/AIDS (MANERELA+) and other allies had organized a forum with the new president, at which women gave testimony about the experience of being HIV-positive, and the devastation wrought by the old drugs. Later, at the outset of the Dialogue, we held a press conference to publicly announce our goals. Because of MANERELA+’s connections, it was surprisingly successful, with more than 25 journalists in the room. Because of our strong and compelling stories, a number stayed to conduct in-depth interviews and report on the proceedings. We got high visibility coverage, including a 20-minute feature at prime time on television. The challenge was how to use this momentum to bring our demands directly to the Health Ministry and president.

CHOICE

Seizing the Moment, Framing the Story

At a key juncture like this, movement work always involves strategic improvisation around opportunities in the moment. Preparation done by the Our Bodies, Our Lives campaign (OBOL)—particularly the development of an agenda and strategy—now enabled a degree of nimbleness in spotlighting our demands. We used a combination of inside strategy (meeting with government officials) and outside strategy (direct-action) to maximize pressure.

+ Read MoreOBOL had decided to participate in the SAVE-organized March to S.A.V.E. Children and Their Mothers from HIV Infections, Stigma & Preventable Deaths, at the end of the conference. In preparation, we used the last night of the Dialogue as a communications session. We developed wonderful feminist messages for placards—one for each woman—and wrote a communiqué expressing all our demands. The morning of the march, about 60 women arrived with painted placards and the communiqué, and joined a range of civic leaders. Because we were better organized (and the only ones with placards), our presence and message took over the march. The leaders of the march drew heavily on our communiqué, and read it on the steps of Parliament. Later, we amplified the power of this moment with a meeting with the Ministry of Health that the Malawi Network of Religious Leaders Living With HIV/AIDS (MANERELA+) helped arrange. At the meeting, we voiced our demands for the necessary resources and accessible modern treatment to save women's lives.

CHANGE

Victory!

Our powerfully-organized constituency, the visibility of our demands, a president sympathetic to women’s issues, well-chosen allies, and a set of additional drivers converged—leading to a change in policy in Malawi. The government agreed to accelerate the rollout plan for new antiretroviral (ARV) drugs, and to significantly address barriers to access. It was a thrilling victory for the women of the Our Bodies, Our Lives campaign (OBOL) and Malawi. We had demonstrated that organized, HIV-positive women can impact policy at the highest level.

+ Read MoreWomen remained determined to fight to make this promise become a reality—to ensure that they and others could live better and healthier lives, free of discrimination and stigma. There was reason to be hopeful, given that the years of movement building had created a new level of organizational capacity. Women whose lives had become transformed as they worked on the campaign, now had the skills, confidence, and relationships to push for further change. A nationwide network of activists, facilitators, and allies at the village, district, and regional levels had been created. Communication capacity to amplify women’s voices and agendas at a district, regional, national, and international level had developed. And capacity for advocacy, that draws on JASS’ global presence, had created access to many important spheres of influence.

+ Transcript/TranscripciónWe finish up with the National Dialogue. One of the last things that we do before the start of the SAVE conference the next day is we have a communications and media session where we all sit on the floor with paint and brushes and card, and we come up with messages, because we are going to be participating in the SAVE organized march, and we need to have placards to take to the march. So every woman does one, so we’ve got over 120 placards. And so the next day its burning hot, and we go to the start of the march, and there’s nobody there, and it’s all a bit chaotic. But there we are with our placards. And for me that moment is about the meaning of preparedness in movement building. You prepare with your constituency in a way that’s fun and real and political, and when you intersect with a potential moment of opportunity, you can seize that moment in its fullness. So not only have we come out with messaging from the National Dialogue that’s feminist messaging around women’s bodies and HIV and ARVs, but we also come out of the National Dialogue with a communique that we have developed together. We intersect with the SAVE process that is not as organized as we are, and what happens? The entire march uses our messaging. So here you have a march of a whole range of civic actors, and we’re the only ones with placards. So the entire march is taken over. So that was a really interesting moment.

The SAVE conference was being organized, but it was an international conference with international markers and indicators, around saving lives of people living with HIV. SAVE again through interesting individual connections, including the fact that a previous MANERALA+ coordinator was the key coordinator of the SAVE conference, we began to start hearing that SAVE had questions about what we were doing in the National Dialogue. I think that the fear was that the women's organizing component would in some way overtake and destabilize SAVE, so I think there was some of that playing out. I also think there were personality positions that were also beginning to accrue, around who was SAVE, and who was the National Dialogue, so that started playing out, and there suddenly became a general nervousness, politically, around what it is that we were doing. And to the point where we actually had somebody from the state machinery, sit outside the National Dialogue meeting room, for the better part of a day, watching in, listening in. That was a very critical moment as well, because it meant that the leadership of the two partner organizations came together in a very specific configuration.

Shereen Essof, JASS Southern Africa

Caja de herramientas

-

Into the Future

The rollout of a new HIV drug began in July 2013. But with successes have come new challenges. In 2014/5 we shifted our focus to ensuring that HIV-positive women could obtain medicine from their own health sites—wherever they might live. That meant strengthening campaign committees across most of the 28 districts of Malawi, making sure people had accurate information, and organizing women in each locale to demand their healthcare rights.

As we move forward, we’re grappling with critical strategy questions. How do we scale up our feminist movement-building schools to support the women’s on-going campaign and expand its reach? How will the campaign thrive and grow, when traditional and faith leaders continue to discriminate—and in some cases encourage women to stop treatment? How do we ensure that women’s bodies and agency are central when it comes to healthcare and access to medicines? How can this organized network of women achieve ever-broader goals—such as increasing access to livelihood supports—and amplify other needs and political interests?

And then there’s the biggest strategy question of all: How do we best continue to organize so that HIV-positive women in Malawi gain the lives they deserve—healthy, happy, and free from stigma and discrimination?

When a woman has been living a life like that of ‘rats on a treadmill’ and is really tired and resigned; when she lives in a state of hopelessness, helplessness and despair, giving up is easy. When all her stored up images and interpretations are based on remembrances and feelings of sadness, self-doubt, distrusts, rejections, abuses and demeaning remarks such as ‘you are HIV positive, you don’t deserve fertiliser coupons, you can’t be allocated land because you are a walking corpse, you have killed many innocent people so you deserve to die, your body is rotten…’ she experiences contradictions in her body. It’s easy to live outside one’s body especially if it has been defined as other, different, lesser, and therefore not human. When she has been labelled and trademarked to the extent that she has embodied what other people say about her, her body is marked with pain. Every scar that puckers on her skin, every stretch mark and every winkle or scar tells a story of where she has been. JASS creates a domain within which the same woman living with HIV continually deepens her understanding of power, sex and resources. It shares with this woman some feminist popular education tools that enable her to realize that she has the capacity to participate actively in the same world that humiliates her. She can be visible and can amplify her voice. With the right tools, especially those that explain how systems of power operate, a huge fundamental shift of mind occurs. She develops a different sense of what it means to be human. This woman starts to appreciate that she is a legitimate citizen, that it’s possible for her life to have meaning. She stops embodying the labels and the trademarks imposed by society. She leaves them behind like a pile of citrus peel. She blossoms into her rightful name.

Hope Chigudu, JASS Southern Africa

+ Transcript/TranscripciónIn fact these spaces started from our respective areas as I said, from the respected areas we are meeting at a national level to the place where it is involving a lot of women country wide. And because it was more about power that was installed in the women, the power within a person, and the power for or the power to. These powers together is the kind of combination that made us to come up with this campaign because the power in me together with the power of other women we managed to hold the duty bailers accountable on the drugs that were being given to us because we believe that there were good drugs that could be given to us as tax payers so we managed to hold them accountable in order for them to procure the quality treatment to be given to us.

When I started imagining a new reality, I imagined I was educated, able to speak English and with some good money in my bag. I refused to be diminished, suppressed, or destroyed. I refused to be warped by bigotry, tyranny, and pettiness. I refused! That is how I crossed the line of an inferiority complex and dependency on men. I am now a member of an HIV support group for sex workers. I know I am a feminist. My body is my own. That is what I tell my sex worker friends. My future plans include buying a plot of land back in Malawi, building a small house and supporting rural-based sex workers to learn to stand on their own feet.

Our Bodies Our Lives

+ Transcript/TranscripciónJASS has changed my life a lot so much so that right now I can say that I have been empowered because at first I was feeling like having HIV is the end of my life but then with the power dynamics and realising all the rights that I have, I have done a lot in my life, like in the movement building school I learnt a lot, so much so that I also had the opportunity to make the decisions of my own like at a family level, at work, and even my career prospects like right now I hold a master’s degree in business administration and I would like to have a PHD hopefully in the near future.

To a newcomer to activism I would say don't give up. Things are not as rosy as they seem to be when they are outside, but when you are inside the movement there are also issues that happen. There are conflicts, but what really needs to push them is what is your passion and what is your aim in joining the movement. So if you really know that you want to contribute to the issues that are happening, then you are most welcome, and please let that be your pusher. ~

Sibongile Singini, Woman Activist, JASS Southern Africa

+ Transcript/TranscripciónI was struck by just how, you know very often when we think about making change happen, right? Many of us often think about, this is how the NGO mindset works, so you’re going to sit in Lilongwe or Harare or Joburg, and you’re going to put together a proposal and it’s going to look very beautiful, and you’re going to sell it and you’re going to conceptualize it, and you have a theory of change, and you have a log frame, and it’s all going to come together. I think that if there’s anything that the experience in Malawi taught me, and taught many of us, is that the work of organizing, mobilizing, starts with very small efforts. You know sometimes one woman at a time, talking about the issues that they care about, no matter how small or insignificant those issues might appear to you as an outsider, taking the necessary time to support them through that journey of self-awareness, self-consciousness, that’s where it begins right? Without a sense of self, without a sense of rights, without a sense of you know this is what I’m entitled to as a human being, you’re not going to move. So all of that stuff we talk about in theory, you know the power within, the power to, etc., and just how much time that takes. And at the same time realizing that once that has been ignited, and I don’t want to put it as a step by step thing, but I think it’s important to recognize that once that power has been unleashed, and women begin to find each other, it is just amazing how unstoppable that becomes, and our role as NGO practitioners, you know people like me who are paid a day job to do this, who don’t necessarily face those challenges ourselves right? It’s for us to understand and take the necessary time and have the patience you know to support those processes, to work with those women at a pace that they control, that they feel comfortable, and then somewhere along the line they will then surprise you -- when you thought you were ambling along, suddenly they want to run.

The women's movement building school is a very safe space for women and it's different from all the trainings I have attended because at first when we were being told that we were about to start a movement I was asking myself - but we are only very few people. By then I think we were about 11 women. We are only very few people; how are we going to reach the whole Malawi? And I was very surprised with how these ladies, the facilitators, conducted their trainings. They started the trainings in a simple way, but then what was acheived was a very big thing. As I am talking we are about thousands of women in Malawi that are involved in this women movement building but at first it started with about 11 people. So it's so amazing to work with JASS, they've got their unique skills, they use unique methodologies to teach people, or to reach out to people.

Jane, Woman Actvist, Malawi

+ Transcript/TranscripciónMy acknowledgment to all women who have contributed to me, whether financial, whether physical support, whatever support they have lent me because it hasn´t changed me only as a person, but it has also changed my family. Because by then I was like ‘Can I educate my children? How?’. But through the process of engaging, through the process of participating, it has also shaped my family too. Because like myself, I got remarried before this activism, I got remarried before even starting the COWLHA, but the perceptions which I had are not the perceptions which I have now, or the strength which I have now, because now I’m seeing to myself to say ‘Why was I getting married again?’, because had it been ‘I have the strength, I have the power, I have the strength which I have now’, I couldn’t do that. Maybe some of the violences which I was facing from my second husband I wouldn’t face those violences. So it’s like, it changed me, and yeah, it changed also the community, because if I see my children being educated, I’m seeing the future of the development of even my community too.

I think we’ve really moved into a point where, because there has been drug roll-out, we are now much more focusing on monitoring the roll-out, because although the drug is available, there is still a lot of the T13 stock, and so health workers might not change you over. And so supporting women activists in their communities to be able to support other women who have been told “no, you don’t need to be changed”, to go back and get changed and show their collective power.

Anna Davies-van Es, JASS Southern Africa

+ Transcript/TranscripciónWhen you do this work, you always have to be open obviously to whatever it is that may present itself. But one of the only ways of that you can be open to dealing with and riding the wave of whatever it is that presents itself is by ensuring that you are so rooted in what it is that you do as feminist movement builders, and that you’ve done the background preparation, even though it may not play out in the way that you have planned, in a way that can allow you to be backstopped by that preparation. So that when you do need to juggle and shift gears from one thing to another very quickly, you can. But I think the other thing that is important in doing this work, and sometimes this is not always possible, but I think the value of having a strong team with multiple skills and strengths, is also critical.