Building Up: Shared Issues, Organization and Leadership

Within each Cycle we offer Key Ideas and Tools to support you wherever you are in your movement building journey. Are you just starting out or are you in the heat of a shaking up moment? What is emerging in your context and what do you want to do? What kind of capacity do you have? Have you thought about risks and safety? These Cycles can be used as a framework for Movement Builders—both experienced and new. So start collecting your tools and store them in your We Rise toolkit.

Building Up is about the power to, coming together with others to find solutions to shared problems and developing our skills, leadership and organization to make change.

-

Understanding Power Examining how power is wielded over us in many ways but also how we can develop our own forms of power to make needed change.

-

Constructing Our Own Analysis Constructing our own evidence and understanding of our context, history, rights, experiences and the current moment. Using this as a foundation of shared political analysis and to inform an alternative vision and action plan.

-

Issues and Organizing Focusing on issues that matter to us, getting others involved, figuring out solutions together and organizing action steps.

-

Collaborative Leadership, Organization and Skills Organizing ourselves to work well together; adopting feminist models of collaboration and leadership, democratic decision-making, distinct roles, mutual accountability, safety, trust, communication.

-

Choosing Alliances and Building Solidarity Forging ties and acting in solidarity with other organizations and individuals who share similar goals, increases our collective power, support and reach.

-

Navigating Difference and Building Political Trust Deepening trust among us by dealing honestly with conflicts that arise, learning from one another, and addressing how differences of identity, position and privilege (e.g. race, gender, ethnicity, class, age, sexuality, ability) can reproduce inequalities and divide us.

-

"Power properly understood is the ability to achieve purpose. It is the strength required to bring about social, political or economic changes. In this sense, power is necessary in order to implement the demands of love & justice."—Martin Luther King Jr. Understanding Power

Understanding Power examines how power over—the power of domination and oppression—operates, and how we can develop our just forms of power to make social and political change happen.

Power is essential. We cannot talk about improving people’s lives, protecting the planet or achieving social change—and certainly not about building and strengthening movements —without talking about power. Simply put, power is about the institutions, structures and beliefs that determine who has privilege, who has access, who sets the rules, whose voice counts, and ultimately, who and what matters and is valued.

+ Read MoreOne way to measure power is through the degree of control exercised over resources: material, human, intellectual, and financial. Although institutions, policies and beliefs take a lot to change, the good news is that power is dynamic and always changing, shaping the social, economic, and political relations between individuals and groups. It affects our lives at every level, from the most intimate—how we view ourselves or how our families work—to all public arenas. Power is neither positive nor negative in and of itself, it is how power is used that matters.

Most people associate power with power over—that is, the ability to control and make decisions for others, with or without their consent. Power over—embedded in discriminatory institutions and belief systems – can take on oppressive and destructive forms, and is perpetuated by threat or use of violence. For example, legislature, military, police, implementing institutions such as the UN, IMF and World Bank. This abuse of power is based on the desire to control finite resources and follows the maxim: “If you get more, I get less.”

If we want to change how power impacts our lives and communities, we have to understand how it is exercised. Many advocacy, social change and human rights strategies focus on only the most visible forms of power over, those exercised through laws, policies, courts, and governmental bodies. While these forms are certainly important, power over also comes in subtler and more insidious forms. These aspects of power, if not understood and addressed, can make any policy victory elusive. For instance, hidden or shadow power operates through actors and organized forces that work behind-the scenes or “under the table” to control what gets on the public agenda and to prevent new ideas and alternatives from gaining ground. Corporations and other non-state actors, like religious groups and organized criminal organizations, for example, use both money and might to manipulate decision-makers and policy agendas, to further their own interests. In many parts of the world, these actors actually control the policy process, a phenomenon called “state capture." The third form of power, which we call invisible power, is made up of the beliefs, customs and values that determine social norms, legitimize or delegitimize ideas and behavior, and shape how we see the world. The forces of invisible power are also ideological, meaning that fears and assumptions about what is right, “normal” and wrong are shaped by the media and messaging from those in power.

Both visible and hidden power forces employ invisible power strategies to legitimize priority agendas and decisions, and to maintain control of public opinion and aspirations. For example, in the United States, conservatives and liberals have long promoted the idea that government is inefficient at service delivery, and that “markets”—or the private sector—can do it better, thereby promoting privatization of healthcare, education and many other services. Similarly, we see how the fear of crime and violence has been manipulated to such a degree that voters in many countries will elect former military generals or will agree to restrictions on their own basic freedoms in the belief that doing so will increase their security. We see that value systems are deeply internalized through socialization processes found in schools, religion, traditions, and/or in the media, advertising, etc. These cultural and educational institutions are most often shaped by those wielding the most power.

“JASS focuses on power not only ‘out there’ in the world, but power within us and between us. Our overarching strategy is to be attuned and responsive to contexts, so that issues we work to solve emerge from organizing, rather than issues driving organizing, as is often the case. We mobilize and negotiate individual and institutional relationships as the context and our strategy demand.”—2011 Crossregional Gathering Participant, “Paths are Made by Walking”

Because many people, and certainly most women, have had negative experiences with the abuse and misuse of power, we can feel paralyzed at the idea of taking a closer look at it. And yet this apprehension puts us at a considerable disadvantage in creating the change we want for our communities. Behind questions of inequality, exploitation and oppression are the dynamics of power and privilege, and if we want to change these realities, we have to become smart navigators of power as well as builders of our own power.

While the dynamics, boundaries, and actors shaping our daily lives constantly shift, the struggle for power continues to stem from control over and access to resources. Those who hold ownership can establish who gets what, who gets left out, and why. Today, the fierce rush to control and exploit resources—from land and forests to technology and human DNA—is a quest for power. It is a fight to determine whose voice will count and what issues will dominate local and global agendas. Throughout this struggle, discrimination and oppression—based on gender, race, ethnicity, class, sexuality, age, location and other factors—play heavily (Lisa VeneKlasen Introduction, Making Change Happen 4: Malawi).

Women’s seemingly "micro" struggles for access and control of resources within the household, family and community are shaped by “macro” dynamics at both national and global levels. Organizing for women’s political and economic empowerment demands an understanding of how power operates in these distinct realms. To further our understanding of the power dynamics behind access to and control of resources we must delve deeper into macroeconomic policy and challenge conventional principles and “truths." We must question racist and patriarchal systems, and associated ideas, values and beliefs that are embedded in all institutions and which shape the choices and attitudes of both men and women. As we seek alternatives for a more sustainable future, much can be learned and gained from how women and other groups on the margins tap into many kinds of resources, utilizing alternate methods to improve lives and promote reciprocity, community and well-being.

To help leaders and activists more effectively unpack, understand, navigate and build power, JASS introduces and applies a power framework co-developed with scholars at the Institute for Development Studies that analyzes the three interactive dimensions of power over. This framework can help us recognize the power dynamics operating in our context on specific problems we are facing, and assist us in determining our strategic and organizing response, given the opportunities for change. These forms of power range from the more formal and visible kinds of power to that of shadow actors that operate behind the scenes to the invisible power of social norms, ideology and values. While the various aspects of power are presented separately, in practice they interact and reinforce one another. We ultimately work to examine power holistically to better form integrated strategies that challenge the webs of discrimination and subordination present in power over. We also introduce people to positive forms of power (power within, power with, power to, power for), which create prospects for forming more inclusive agendas, equitable political relationships and social structures to transform power over. By affirming people’s capacity to act creatively, these alternatives provide some basic principles for constructing empowering strategies.

One way to measure power is through the degree of control exercised over resources: material, human, intellectual, and financial. Although institutions, policies and beliefs take a lot to change, the good news is that power is dynamic and always changing, shaping the social, economic, and political relations between individuals and groups. It affects our lives at every level, from the most intimate—how we view ourselves or how our families work—to all public arenas. Power is neither positive nor negative in and of itself. It is how power is used that matters.

Most people associate power with power over, the ability to control and make decisions for others, with or without their consent. Power over, embedded in discriminatory institutions and belief systems, can take on oppressive and destructive forms, and is perpetuated by threat or use of violence, for example, governments, military, police, and multilateral institutions such as the IMF, WTO and World Bank. This abuse of power is based on the desire to control finite resources and follows the maxim: “If you get less, I get more.”

If we want to change how power impacts our lives and communities, we have to understand how it is exercised. Many advocacy, social change and human rights strategies focus on only the most visible forms of power over, those exercised through laws, policies, courts and governmental bodies. While these forms are certainly important, power over also comes in subtler and more insidious forms. These aspects of power, if not understood and addressed, can make any policy victory elusive. For instance, hidden or shadow power operates through actors and organized forces that work behind-the scenes or “under the table” to control what gets on the public agenda and to prevent new ideas and alternatives from gaining ground. Corporations and other non-state actors, like religious groups and organized criminal organizations, for example, use both money and might to manipulate decision-makers and policy agendas to further their own interests. In many parts of the world, these actors control the policy process.

The third form of power, which we call invisible power, is made up of the beliefs, customs and values that determine social norms, legitimize or delegitimize ideas and behavior, and shape how we see the world. The forces of invisible power are also ideological, meaning that fears and assumptions about what is right, “normal” and wrong are shaped by the media and messaging from those in power.

Both visible and hidden power employ invisible power strategies to legitimize priority agendas and decisions, and to maintain control of public opinion and aspirations. For example, in the United States, conservatives and liberals have long promoted the idea that government is inefficient at service delivery, and that “markets”—or the private sector—are more efficient, promoting privatization of healthcare, education and many other services. Similarly, we see how the fear of crime and violence has been manipulated to such a degree that voters in many countries will elect former military generals or will agree to restrictions on their basic freedoms in the belief that doing so will increase their security. We see that value systems are deeply internalized through socialization processes found in schools, religion, traditions, and/or in the media, advertising, etc. These cultural and educational institutions are shaped by those wielding the most power.

“JASS focuses on power not only ‘out there’ in the world, but power within us and between us. Our overarching strategy is to be attuned and responsive to contexts, so that issues we work to solve emerge from organizing, rather than issues driving organizing, as is often the case. We mobilize and negotiate individual and institutional relationships as the context and our strategy demand.”—2011 Crossregional Gathering Participant, “Paths are Made by Walking”

Because many people, and certainly most women, have had negative experiences with the abuse and misuse of power, we can feel paralyzed at the idea of taking a closer look at it. And yet we have to understand and confront power to create the change we want for our communities. Behind questions of inequality, exploitation and oppression are the dynamics of power and privilege, and if we want to change these realities, we have to learn to navigate power and become builders of our own power.

The dynamics, boundaries, and actors shaping our daily lives constantly shift, but the struggle for power continues to stem from control over and access to resources. Those who hold ownership can establish who gets what, who gets left out, and why. Today, the fierce rush to control and exploit resources—from land and forests to technology and human DNA—is a quest for power. It is a fight to determine whose voice will count and what issues will dominate local and global agendas. In this struggle for power, they use the historical instruments of discrimination and oppression, to concentrate resources and power in a very few hands, generally of white men.—Lisa VeneKlasen. Introduction, Making Change Happen 4: Malawi.

Women’s seemingly "micro" struggles for access and control of resources within the household, family and community are shaped by “macro” dynamics at both national and global levels. Organizing for women’s political and economic empowerment demands an understanding of how power operates in these distinct realms. To further our understanding of the power dynamics behind access to and control of resources, we must deepen our critical analysis of capitalist macroeconomic policy and challenge conventional principles and “truths". We must question racist and patriarchal systems, and associated ideas, values and beliefs that are embedded in all institutions and that shape the choices and attitudes of both men and women. As we seek other models for a more sustainable future, much can be learned and gained from how women and other groups on the margins, with a great deal of autonomy and creativity, tap into many kinds of resources, utilizing alternate methods to improve lives and promote reciprocity, community and well-being.

To help leaders and activists more effectively unpack, understand, navigate and build power, JASS introduces and applies a power framework co-developed with scholars at the Institute for Development Studies that analyzes the three interactive dimensions of power over. This framework can help us recognize the power dynamics operating in our context on specific problems we are facing, and assist us in determining our strategic and organizing response, given the opportunities for change. These forms of power range from the more formal and visible kinds of power to that of shadow actors that operate behind the scenes to the invisible power of social norms, ideology and values.

While the various aspects of power are presented separately, in practice they interact and reinforce one another. We ultimately work to examine power holistically to better form integrated strategies that challenge the webs of discrimination and subordination present in power over. We also introduce people to positive forms of power (power within, power with, power to, power for), which create prospects for forming more inclusive agendas, equitable political relationships and social structures to transform power over. By affirming people’s capacity to act creatively, these alternatives provide some basic principles for constructing empowering strategies.

Tools for Understanding Power

-

Vivi: I was very enlightened by the power analysis where there's a lot of invisible power beneath everything. One phrase that stuck with me was the "internalization of values." It had profound meaning to me. I realized that fundamental change came with changing values.

-

Amina: I always say that feminist leadership for me is about understanding power and understanding privilege, and about understanding position – the 3 P’s.

Amina: I always say that feminist leadership for me is about understanding power and understanding privilege, and about understanding position – the 3 P’s. -

Malena: Power operates in all aspects of our lives, both the public and private realms. We experience it within our families, in the community, in any decision-making. It is a RELATIONSHIP between persons, social classes, genders, ethnic groups, generations, territories, states, and institutions. That relationship can be expressed as a form of power over in which some can seek to control or dominate others. This often gives rise to resistance, confrontation, transgression and negotiation. Power also can be based on relations of equality, an expression of transformative power.

-

Linnah: Women-only spaces make us strong. We come together and become friends. We understand the problems in our lives. We see how power works, those with power over us and the power within ourselves. We see together that we have the collective power to make change in our lives.

Linnah: Women-only spaces make us strong. We come together and become friends. We understand the problems in our lives. We see how power works, those with power over us and the power within ourselves. We see together that we have the collective power to make change in our lives. -

Lisa: Currently, policymakers tend to look to (Western) science and technology for all answers. But, although these are all critical, power plays a greater role in legitimizing which knowledge counts. Who has privilege, who has access, who sets the rules, who matters, who has a voice—these are all determined by the power dynamics embedded in any society and in political institutions. Take climate change. One of the greatest impediments to governments moving forward on alternate forms of energy is the extraordinary power of the fossil fuel industry. Large corporations really shape the public and policy dialogue and determine what issues reach the public agenda, what role science plays, and how policymakers act. And yet activists are organized now in ways that are impacting these powerful players.

-

Phumi: We see a lot of strategies that focus on visible power and how it operates: advocacy work, working through the courts, going to police stations, changing a bill, enacting a law, and so on. And yet the real power is often behind the scenes, behind closed doors, behind the president, behind the parliamentarian, behind the face of formal power. What this means in practice is working with the movements we support to ensure that their strategies and tactics take into account how hidden and invisible power operate: the norms, beliefs, values, and ideologies that underpin our understanding of ourselves in the world and that are influencing or controlling the policy agenda. It’s here that we need to do the most work to shift norms and values that underpin policy.

Phumi: We see a lot of strategies that focus on visible power and how it operates: advocacy work, working through the courts, going to police stations, changing a bill, enacting a law, and so on. And yet the real power is often behind the scenes, behind closed doors, behind the president, behind the parliamentarian, behind the face of formal power. What this means in practice is working with the movements we support to ensure that their strategies and tactics take into account how hidden and invisible power operate: the norms, beliefs, values, and ideologies that underpin our understanding of ourselves in the world and that are influencing or controlling the policy agenda. It’s here that we need to do the most work to shift norms and values that underpin policy. -

Erma: I was reminded again of the many dimensions of power and its impact on women's lives. I was unaware of the power that my family and community can have in influencing the way I think. This session increased my level of critical awareness.

-

Malena: Power is dynamic. It’s always changing and there are always contradictions. It’s important to recognize that with all our strategies.

Malena: Power is dynamic. It’s always changing and there are always contradictions. It’s important to recognize that with all our strategies. -

Phumi: We see how powerful it can be for movements to look at the world through a power lens. It enables them to think about the power players in relation to their own lives and struggles. This is important because we often do not understand how powerful groups invisibly undermine people’s rights.

-

-

“Women are knowledgeable about the issues that affect them. They should always be consulted on every project conducted on their communities.”—Lillian Namukasa Constructing Our Own Analysis

Constructing Our Own Analysis is a key step in building collective power and a joint agenda. It involves gathering our own evidence based on our experience developing an understanding of our context, history, rights and the current moment. The process also involves weaving together our own knowledge with new ideas and information. A shared analysis is the foundation for good strategy and an alternative vision of the solutions and the world we want to create.

+ Read MoreA change strategy begins with a deeper understanding of the contexts and problems that need solving. Building our own analysis by understanding the local, national and global politics and policies shaping our issues and options is a key part of leadership development and organizing. It enables us to identify a possible issue that could serve as an entry point to tackle a bigger agenda. Sometimes these “entry point issues” emerge in very informal settings. For example, in our work in Malawi with women affected by HIV/AIDS, the issue that emerged in informal gatherings where women could speak in confidence was how outdated ARV drugs were being routinely distributed despite the fact that they were deforming women’s bodies. In Southeast Asia, informal evening sessions with young women revealed that fundamentalist groups control how women are supposed to behave, including what they wear – a subject that had never come up in more public dialogues. In Mesoamerica, informal safe space revealed that women activists feared the verbal attacks that labeled them “bad mothers” as much as other threats, such as physical harm.

There are many ways to build our own analysis. The general process usually starts with exploring and identifying the root causes of a problem, including the key players, their agendas (both stated and unstated), the dynamics and how they affect different people. This helps to determine the impact of the problem to be solved, and the particular forces, systems and trends at work in a given society.

Women involved in our movement-building processes learn to use a power framework, along with other tools and methods of reflection and analysis developed by scholars and popular educators, to assess their contexts and issues, and to understand key historical moments as the foundation for developing strategies and solutions to their problems.

Other methodologies we use include creating a timeline of political and economic changes, and of the responses by social and women’s movements in those particular contexts. This exercise often enables activists to appreciate the advances that have been made by others before them, and also to understand how change is often not linear.

Tools for Constructing Our Own Analysis

ON-THE-GROUND CONVERSATION…

Hear what Lisa VenKlasen, Adelaide Mazwarira, Hope Chigudu, Everjoice Win, Anna Davies-van Es, Marlien Elvira “Vivi” Marantika, Sui Sui and Mariela Arce have to say about Constructing Our Own Analysis based in our deep knowledge, experience and data gathering to inform meaningful solutions and strategies.

-

Adelaide: In one of our trainings, a woman from Uganda said: “Women are knowledgeable about the issues that affect them. They should always be consulted on every project conducted on their communities.” That’s the basis of constructing our own analysis.

-

Lisa: We want to move away from calling ourselves “trainers” because our approach to knowledge is much more political and dynamic. We’re not delivering knowledge to those who don’t know; we are generating knowledge collectively from personal and political experience, with new ideas and how-to’s woven in. The process forges relationships between women that are critical for movement-building, and the knowledge guides our collective action.

Lisa: We want to move away from calling ourselves “trainers” because our approach to knowledge is much more political and dynamic. We’re not delivering knowledge to those who don’t know; we are generating knowledge collectively from personal and political experience, with new ideas and how-to’s woven in. The process forges relationships between women that are critical for movement-building, and the knowledge guides our collective action. -

Mariela: The JASS Mesoamerica School of Feminist Alchemy (Escuela de Alquimia Feminista) is a space where women from different organizations come together to learn, build collective knowledge, and exchange experiences and strategies. Alquimia is a place not only for academic or theoretical training, but also for the exchange of strategies of struggle and experiences of resilience. It’s a space where collective dreams and learning processes are generated by both the popular educators and the activists who participate in these trainings. This allows the generation of new visions and new frameworks to interpret reality and raise the quality of feminist analyses based on a transformative practice.

-

Marlien Elvira “Vivi”: Mapping the shared experiences and problems faced by indigenous women both in Southeast Asia and Mesoamerica was one of the most valuable lessons I learned from JASS. It showed me that even though we as indigenous women are not part of formal decision-making processes at many levels, we bear much of the burden of its impact. Building from the collective power of indigenous peoples’ local experience, organizing indigenous women is not only strategic—it is imperative.

Marlien Elvira “Vivi”: Mapping the shared experiences and problems faced by indigenous women both in Southeast Asia and Mesoamerica was one of the most valuable lessons I learned from JASS. It showed me that even though we as indigenous women are not part of formal decision-making processes at many levels, we bear much of the burden of its impact. Building from the collective power of indigenous peoples’ local experience, organizing indigenous women is not only strategic—it is imperative. -

Sui Sui: From other organizations, we learn concepts. But, these concepts are very heavy and hard to follow. With JASS, we don’t go too far too fast. JASS feels it out with us and helps us to express ourselves by letting us determine what is suitable to strive for in our own community.

-

Hope: We encouraged story-telling in our process in Malawi because we knew women would be comfortable with it and it would portray a much richer picture of their lives. As well, the stories were used as a context for a broad discussion in which the opinion of each person was taken seriously. The discussions shed light on the women’s context, culture and experiences in relation to shifts in power and relationship.

Hope: We encouraged story-telling in our process in Malawi because we knew women would be comfortable with it and it would portray a much richer picture of their lives. As well, the stories were used as a context for a broad discussion in which the opinion of each person was taken seriously. The discussions shed light on the women’s context, culture and experiences in relation to shifts in power and relationship. -

Everjoice: One thing I saw in the context [Southern Africa] is that there had not been deep enough conversations on sex, sexuality, sexual autonomy and bodily integrity. We had opened the door on LBTI women, and that’s powerful. But we also needed to talk about what it means to be female, to have a female body and a vagina.

-

Hope: The Body Mapping exercise was a way of getting to much deeper stories about what was happening in the women’s lives. Their pain, the stigma (of HIV status), the intimate reality of their bodies and their survival strategies. So much came to light.

Hope: The Body Mapping exercise was a way of getting to much deeper stories about what was happening in the women’s lives. Their pain, the stigma (of HIV status), the intimate reality of their bodies and their survival strategies. So much came to light. -

Anna: We went beyond stories too. The [HIV positive] women were reporting problems with access to treatment and the prescription of old toxic drugs. But what we had was anecdotal, not rigorous evidence we could take to the Ministry of Health. No one had that data. So we decided we had to gather it ourselves. Using participatory research, 60 women we trained generated 900 interviews documenting what was happening.

-

Mariela: It is essential that among ourselves we know how to identify a common context analysis and the positions of the stakeholders and therefore can build common positions on key issues that we agree to work on. Regardless of whether you do it one way and I do it another, it is particularly important to build this common vision and political purpose.

Mariela: It is essential that among ourselves we know how to identify a common context analysis and the positions of the stakeholders and therefore can build common positions on key issues that we agree to work on. Regardless of whether you do it one way and I do it another, it is particularly important to build this common vision and political purpose.

-

-

“Every human being has the capacity to rebel and transgress, to cross the line of oppression but usually a catalyst is required to invoke and politicize the spirit of rebellion.”—Hope Chigudu Organizing & Issues

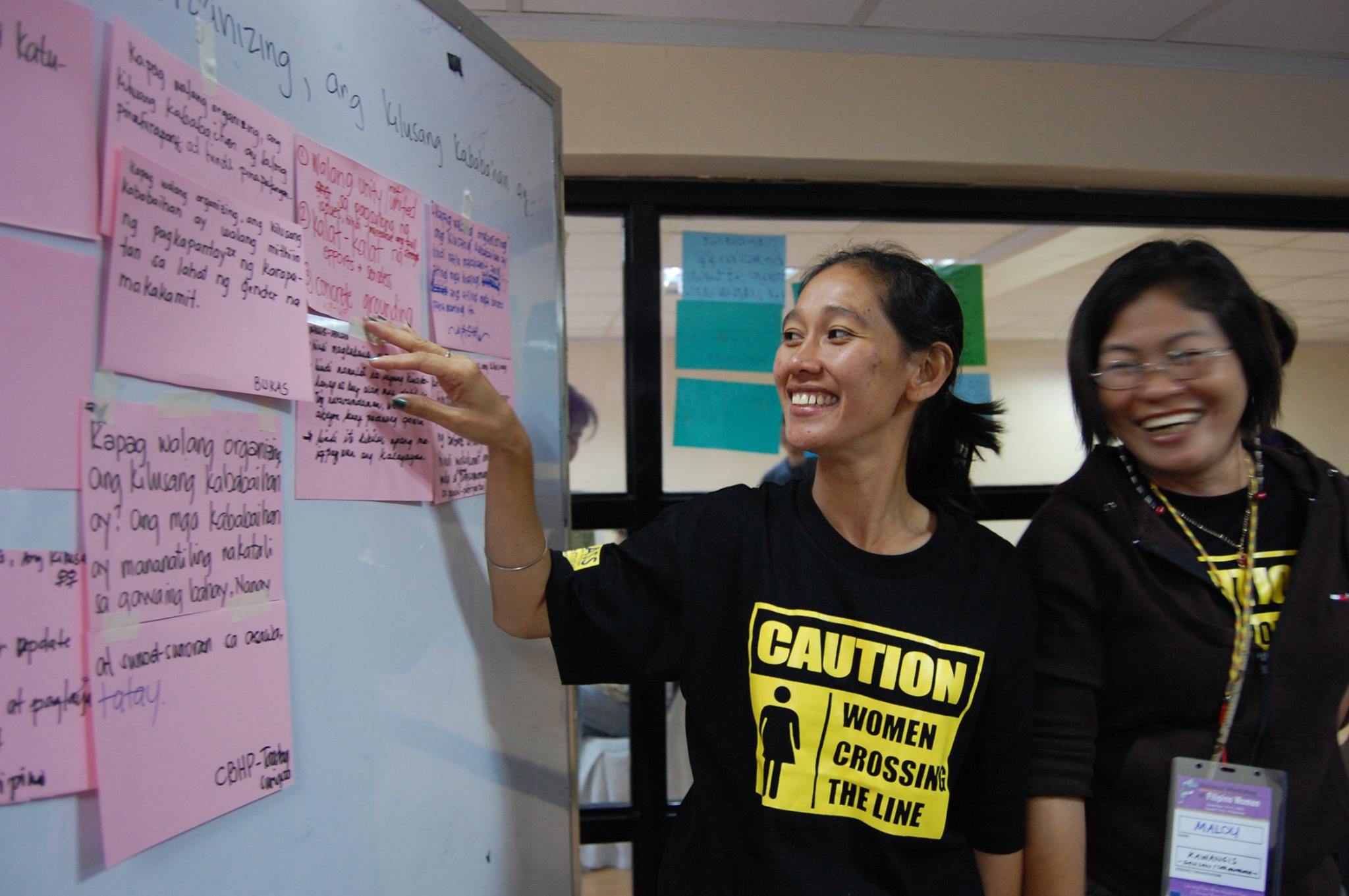

Organizing & Issues is about coming together with people who share a common set of problems, talking through those problems, committing to collective action, imagining solutions together, and developing strategies to achieve those goals while also getting others involved.

“Organizing is old-fashioned, face-to-face relationship-building. It is action-oriented at a community level, one person at a time.”—Lisa VeneKlasen

+ Read MoreActivists often confuse organizing and mobilizing—they are actually two inter-dependent elements of movement-building. Organizing is the process of dialogue and collective analysis through which people are able to find common ground with others and take leadership in finding solutions. Organizing is the deep essential component of anchoring a change strategy with the people most affected by a set of issues, whose knowledge from living with those problems is a key ingredient in the solution. Mobilizing refers to the sets of actions taken to call attention to the issue and to pressure for change.

A misconception exists that only issues that directly relate to civil and political rights and justice are strategic. In most communities directly impacted by inequality and injustice, the defense of political rights cannot be done without also organizing to address practical needs. In fact, organizing around practical needs is often the most strategic entry point for long-term movement-building. For example, in a context of poverty, given women’s care-giving roles, we must collectively address survival issues, like food and childcare, to provide the freedom and the organizational foundation for taking action for other rights over the long-haul.

Long-time labor organizer, Jane MacAlvey, helps explain the "how":

“Organizing isn’t rocket science, but it is a serious skill and a craft. We have to build an army of people in the field who can actually contend with capital on the local level… It’s 70/30: 70 percent listening and 30 percent talking. Even the 30 percent talking is really agitational; it’s a series of specific questions that allow people to begin to self-analyze the crisis in their life. No one walks up to a worker and says, ‘You know what the problem with capitalism is? Your boss is really f*in’ you.’ Workers know their boss is screwing them!”

MacAlvey goes on to say, “Organizing tools and an organizing conversation are literally about a process of self-discovery. People begin to systematize and analyze what’s going wrong in their life. So it is people’s own experience, moving toward something broader, that can then bring them out together.” Jane MacAlvey and Michael R, Jacobin. “The Big Difference Between Organizing and Mobilizing: How Unions Can Win in the Future” Alternet, October 21, 2015.

JASS’ organizing efforts begin through the creation of women-only safe spaces where women come together and share experiences from their lives. These spaces make them strong as they build relationships and solidarity in their shared struggles. By understanding power first through the lens of their lives, women recognize and gain hope from the power they have. It also provides an opportunity to dream and imagine alternatives for themselves and their families.

Tools for Issues & Organizing

ON-THE-GROUND CONVERSATION…

Join a conversation with Alexa Bradley, Sibongile Singini, Zephanie Repollo and Nani Zulminari about the deep step-by-step work to build relationships and trust, forge collective action and motivate people around issues they care about.

-

Zephanie: Identifying and organizing around key issues brings people together. It forms collective unity and support and joint strategy for them to be able to achieve their common goals. In some contexts there’s a lot of mistrust, but focusing on key issues they can work with brings them together to set aside the differences.

Zephanie: Identifying and organizing around key issues brings people together. It forms collective unity and support and joint strategy for them to be able to achieve their common goals. In some contexts there’s a lot of mistrust, but focusing on key issues they can work with brings them together to set aside the differences. -

Nani: In our work with PEKKA, we start from zero, talking one by one with each woman to find out her primary concerns. Women always start with the problem of money. So we begin with a group savings project as a practical way to bring women together. By pooling these small earnings, they are able to invest in joint economic endeavors. As individuals, they become more independent; as a group, they begin to understand the potential of their economic and political power.

-

Sibongile: It’s important that those that are directly impacted by the issues are the ones that are defining and driving the agenda of the movement. This enables women to amplify the support and acceptance of their agenda, and grow in numbers, because people will own the issues that the movement is seeking to transform, and will get involved to bring about the desired change.

Sibongile: It’s important that those that are directly impacted by the issues are the ones that are defining and driving the agenda of the movement. This enables women to amplify the support and acceptance of their agenda, and grow in numbers, because people will own the issues that the movement is seeking to transform, and will get involved to bring about the desired change. -

Alexa: We should always think about how our short-term work is helping us get closer to our bigger goals too, helping us develop our skills, build key relationships, alliances, to learn how to be strategic, how to work collaboratively. That is what organizing is about. You start somewhere, and you build.

-

Nani: As we set up democratic cooperatives, women also gain experience in leadership, decision-making, and democracy. One woman, one vote, equal rights. This system fosters more practical and emotional independence. Of course, this work takes lots of consciousness raising and capacity building. We don’t attach women to an existing cooperative. They build their own together.

Nani: As we set up democratic cooperatives, women also gain experience in leadership, decision-making, and democracy. One woman, one vote, equal rights. This system fosters more practical and emotional independence. Of course, this work takes lots of consciousness raising and capacity building. We don’t attach women to an existing cooperative. They build their own together. -

Alexa: You don’t want to create an organizing strategy that suddenly puts people’s lives at risk. When we organize, we build our capacity together. We build our tolerance for risk. We build our strategy. we can’t recklessly dive into a problem when there are risks of imprisonment, repression or violence. And we never want to knowingly lead people into defeat. So we need to look at our ultimate goal, and systematically identify steps we can take that let us accomplish something. We want to foster a positive experience of power, not reiterate a negative experience.

-

Nani: Economic organizing actually enables us to work under oppressive governments. We tell governments that we’re working in savings and credit, and then the authorities leave us alone. Interestingly, over time, our experience has shown that women will promote their own leaders to become village head or members of the village parliament. From there, they have greater influence, gain more power, and can make bigger changes.

Nani: Economic organizing actually enables us to work under oppressive governments. We tell governments that we’re working in savings and credit, and then the authorities leave us alone. Interestingly, over time, our experience has shown that women will promote their own leaders to become village head or members of the village parliament. From there, they have greater influence, gain more power, and can make bigger changes.

-

-

"In our work with democratic cooperatives, women also practice new leadership, decision-making and democracy: one women, one vote, equal rights. This leads to more practical and emotional independence."—Nani Zulminarni, PEKKA & JASS SEA Collaborative Leadership, Organization & Skills

Collaborative feminist leadership, organization and skills describes one of the most fundamental aspects of Building Up—the coming together of a group of people to organize to achieve something more than any of them could achieve alone. This collaboration can take many forms—the creation of a community group, an organization, a network, a cooperative, etc.—but it always involves a decision to work together in a sustained way around a shared goal or effort.

+ Read MoreWe have to build leadership and determine the processes of decision-making that will serve us, how members will be mutually accountable, how we will manage whatever resources we have and who will do what. But forming an organization is not just a set of technical decisions—it requires a simultaneous process of relationship and trust-building on the one hand, and skill and capacity development on the other.

Organization is about building collective power. Together we can be heard, we can do more, we can break isolating individualism, we can protect ourselves better, we can challenge injustice and make change more readily. Collective power is not just about outcomes, however. It is also about emboldening ourselves, about creating the space to reimagine and envision alternatives and solutions, about the practice of collaboration, leadership and democratic decision-making—all essential to the future we are working to create. We don’t just demand equality and democracy, we practice it.

A movement-building approach to building organization recognizes the need to take great care in how we build and the patterns we form. Activists cannot expect that the experience of being excluded prepares people to become inclusive, collaborative and democratic leaders. In the absence of alternative models and relationships, people often will repeat the patterns of power with which they are familiar, at times “imitating the oppressor.” New skills and forms of leadership, decision-making and conflict navigation must be explicitly defined, taught, and practiced in order to create democratic forms of power. As part of this process, the underlying values of the organization need to be regularly clarified and operationalized, emphasizing those that support justice, equity and compassion.

We begin with safe space, a place for women and those too-often silenced to come forward with all of who we are —our experiences, struggles, dreams—and be seen and heard. We use Feminist Popular Education, a learning approach born in Latin America where people learn together by critically examining their lives and contexts, and the issues that matter most to them, affirming and deepening their existing knowledge and developing a shared analysis of their context. By questioning the structural and ideological causes of these issues, the learning process raises awareness, helps empower people, and defines a shared agenda for organizing and joint actions.

The seeds of collaboration are planted in this process of discovering acceptance and common ground with others. Moving from isolation into community opens the doorway to working together, often starting with tackling simple issues and solutions close to the daily lives of those involved. It is this convergence of a sense of power within and power with others that energizes collaboration and the development of a new organization.

There are two main challenges in building leadership: fostering self-confidence and leadership skills in members, and breaking with patriarchal models. For women and others who have often been systematically excluded from social leadership roles, one of the first hurdles is being able to see oneself as a leader and decision maker. While many have held significant responsibility in families and households, because those roles are in what is considered the “private” realm, they are not afforded the same value, they remain invisible in the social hierarchy and women themselves often don’t recognize them.

And unfortunately, the most common models of leadership most have experienced are top-down and patriarchal. Establishing an organization that truly invites and foments the leadership of everyone involved requires deliberate choices, consciousness and specific skill development to work against the social and cultural barriers that reinforce damaging social hierarchies, and to cultivate feminist collaborative practices of leadership. Support for taking on new roles and building effective organizations is very important so new leaders don’t get overwhelmed or recreate divisive or oppressive power dynamics and structures.

“Patriarchy, reflected through all the structures and institutions of our world, is a system that glorifies domination, control, violence, competitiveness and greed. It dehumanizes men as much as it denies women their humanity. So we need leadership that will explore and expose these links and challenge patriarchy. The only leadership that does this is feminist leadership.” Peggy Antrobus

Feminist leadership focuses on the basic principles of distributive leadership, collective decision-making, means that are congruent with the ends, non-violence and building power with and power to, rather than power over. Feminist leadership principles and practice that emphasize a shared commitment to expanding leadership, with opportunities for training and learning while doing, fundamentally changes how we organize and how we lead change.

Tools for Collaborative Leadership, Organization & Skills

ON-THE-GROUND CONVERSATION…

Joanne Sandler, Nani Zulminari, Kunthea Chan, Valerie Miller and Amina Doherty reflect on why building collaborative, feminist leadership and decision-making skills are essential for building movements that can weather conflict, lift up women’s strengths, increase our power and win demands.

-

Amina: When we talk about feminist leadership, one of the most important things to center is an analysis of power, including an understanding of your own power, positionality and privilege.

Amina: When we talk about feminist leadership, one of the most important things to center is an analysis of power, including an understanding of your own power, positionality and privilege. -

Nani: Building leadership is a step-by-step process. When we start out working with the women they have never seen themselves as decision makers. So we build decision-making in from the beginning. For example, at our first meeting of the new collective, they have to name their group together. This is their first decision outside their family.

-

Valerie: We have been educated in a model of leadership that is very individualistic. I remember when the women in the Alquimia workshop first drew their idea of leadership—it was this huge amazing woman on top of a podium with tiny women at her feet. That’s our traditional vision of leadership, heroic or domineering leadership. We have to go beyond that.

Valerie: We have been educated in a model of leadership that is very individualistic. I remember when the women in the Alquimia workshop first drew their idea of leadership—it was this huge amazing woman on top of a podium with tiny women at her feet. That’s our traditional vision of leadership, heroic or domineering leadership. We have to go beyond that. -

Joanne: The incentive system includes romanticizing the heroic individual, which is a legacy of patriarchy, and since we all have patriarchy inside of us, we all conform to this practice at some level because it’s so subconscious.

-

Mariela: I do not believe in ‘super leaders’ because that also is a ‘Must Be’ and a label. I do not believe that we feminists have to re-impose ‘Must Be’ expectations on ourselves in order to be good, excellent, and perfect feminist leaders. I believe that there is an amalgamation and an alchemy of the stories and of the things that make up your identity as a person, as a human being, as a woman, which you project on the political task when you try to contribute your knowledge, experiences, and skills to bring about change. There are people who have wonderful skills to build bridges between women, to generate alliances, to foster dialogue, to create spaces of sisterhood, empathy, compassion, and kindness among us. And for me that is the amniotic fluid, that quality, warmth, and generosity of people -- and especially of women with women and with the world.

Mariela: I do not believe in ‘super leaders’ because that also is a ‘Must Be’ and a label. I do not believe that we feminists have to re-impose ‘Must Be’ expectations on ourselves in order to be good, excellent, and perfect feminist leaders. I believe that there is an amalgamation and an alchemy of the stories and of the things that make up your identity as a person, as a human being, as a woman, which you project on the political task when you try to contribute your knowledge, experiences, and skills to bring about change. There are people who have wonderful skills to build bridges between women, to generate alliances, to foster dialogue, to create spaces of sisterhood, empathy, compassion, and kindness among us. And for me that is the amniotic fluid, that quality, warmth, and generosity of people -- and especially of women with women and with the world. -

Nani: As we build PEKKA, we focus on women's experiences of leadership and working together always. We are not just about savings collectives, that is just where we start. With every step of the work, we look for how we can develop women’s leadership skills-- from how to run a meeting to how to keep the books to how to impact the courts and media. Women learn the value of working together, of democratic culture, and it keeps growing.

-

Kunthea: JASS has developed feminist leadership principles over many decades and currently works on applying and refining them through training in our feminist movement building schools. This training uses an evolving, highly interactive, feminist popular education curriculum that focuses on giving women who are already involved in grassroots organizing the confidence, skills, allies, and strategies they need to be stronger and make their movements stronger.

Kunthea: JASS has developed feminist leadership principles over many decades and currently works on applying and refining them through training in our feminist movement building schools. This training uses an evolving, highly interactive, feminist popular education curriculum that focuses on giving women who are already involved in grassroots organizing the confidence, skills, allies, and strategies they need to be stronger and make their movements stronger. -

Paty: The training processes in our School of Feminist Alchemy (Escuela de Alquimia Feminista) seek not only to recover the knowledge of all those who participate in these processes, but also to promote alliances and collaboration among us all. As participants progress – on the basis of their own realities and with JASS providing feedback from our experience in feminist popular education -- we discover that feminism is somehow intrinsic to the need to change and transform women’s reality. For us that perspective, which is explicitly feminist from the beginning, constitutes something that we seek as a point of arrival. Relative to the situation of the women, our starting point is not necessarily that the women call themselves feminists, but rather that they discover the feminism that is internalized in their reality and in their struggles.

-

Amina: Feminist leadership is beautiful because you’re in a state of constant re-learning. You don’t come to a process assuming that you know everything, but it also allows you to be strong in your beliefs and in your values. I think understanding leadership in these terms has transformed the way that I work, and the way that I interact with people. Recognizing yourself as a vessel that is constantly learning, building, and growing is something that I think is really unique and special about feminist leadership.

Amina: Feminist leadership is beautiful because you’re in a state of constant re-learning. You don’t come to a process assuming that you know everything, but it also allows you to be strong in your beliefs and in your values. I think understanding leadership in these terms has transformed the way that I work, and the way that I interact with people. Recognizing yourself as a vessel that is constantly learning, building, and growing is something that I think is really unique and special about feminist leadership. -

Mariela: Feminist leadership is creative and has brought back holistic expressions of culture and art, as well as communication and political protest. It uses whole language for political activity and to communicate feelings. Hand in hand with that, feminist leadership always appeals to spirituality, to emotion, to the sense of outrage. It uses the language of human communication and works a lot with narratives, with language justice, with historical visibility and identity, so that people can identify from their daily lives with what women are denouncing.

-

-

“If we want change, we have to be a little more open. We have a lot to learn from allies, because we cannot solve the challenges we face on our own.”—Patricia Ardon Choosing Allies & Building Solidarity

Choosing Allies and Building Solidarity are the foundation of “power with” - the relationships among groups and individuals who come together to create the collective power needed to advance a social and political change agenda. Identifying and forging relationships with potential allies - from the local community to national and even global levels is essential to both our movement strategies and our safety as activists.

+ Read MoreAllies come in many forms. Those organizations and people who agree with and are aligned with your goals; those that may just agree with a specific issue or demand; some are long term strategic partners, others are tactical allies with whom you share a more narrow collaboration. When we look for allies, we look for different things - allies that bring a vast constituency to our efforts or allies that have influence with key decision makers or powerbrokers. We may choose an ally because they bring needed resources, access or capacities.

Solidarity, the commitment to mutual support and to “have each other’s back”, is an essential element in the relationship with allies because it is a concrete demonstration of political unity and empathy. It is about showing up and making common cause with another community’s struggle. It is about seeing your struggles and your liberation as interconnected

“The many situations of inequality, poverty and injustice are signs not only of a profound lack of fraternity, but also of the absence of a culture of solidarity. New ideologies, characterized by rampant individualism, egocentrism and materialistic consumerism, weaken social bonds, fueling that 'throw away' mentality which leads to contempt for, and the abandonment of, the weakest and those considered 'useless.'" —Pope Francis

The forces of inequality and violence demand that we work together in our communities and across borders, identities and issue-specific agendas to create a sufficiently powerful counterweight and alternative. Alliances and solidarity networks are not just our source of power for change; with some smart organizing, they can also be our safety net and source of hope.

Alliances are a necessity and a key ingredient in social justice organizing and movement building. They can amplify our influence, offer additional resources, open doors and enhance our legitimacy. They ground our efforts and extend our reach. Our work, and in turn, our partnerships, are driven by the priorities of organized constituencies of the people most affected by inequality and violence, most often women. Rather than building small, isolated, micro-level movements, our goal is to create “meshworks,” or webs of diverse alliances and movements working in different places with common values and vision. Most importantly, “meshworks” are anchored by the leadership and experiences of the communities and people most affected.

“We need to be more flexible in our thinking about various ways of working together across differences. Some formations may be more permanent and some may be short-term. However, we often assume that the disbanding of a coalition or alliance marks a moment of failure, which we would rather forget. As a consequence, we often fail to incorporate a sense of the accomplishments, as well as of the weaknesses, of that formation into our collective and organizational memories. Without this memory, we are often condemned to start from scratch each time we set out to build new coalitional forms.” ― Angela Davis

Below are some guiding principles for building successful alliances:

- Choose your allies carefully. To evaluate your potential allies, your organization should have a prior relationship and trust built on direct experience and effective communication over time. Building that trust will continue to be a long-term, ongoing process.

- There should be compatibility around vision, values, political orientation, style, and institutional maturity and a shared contextual analysis.

- Your alliance will be stronger than the sum of its parts if you choose allies that have complementary strengths and resources.

- Alliances require constant monitoring and nurturing. Effective alliances are only as strong as the organizations that make them up and the relationships between them.

To be a successful ally requires:

- Clarity about identity, role and responsibilities within the alliance

- Investment in the goal of the alliance and its success.

- Organizational self-awareness (ability to communicate vision, values, objectives, etc.).

- A dedicated point person to ensure consistency of communication and relationship building.

- Commitment to transparency.

- Realistic assessment of the time and resources required and capacity to mobilize those resources for the duration of the alliance.

- Successful alliances operate on the principles of solidarity, mutual benefit and accountability, and reciprocity. To build an effective alliance requires:

- Dedicating enough time to get to know each other, surface potential differences (e.g., in strategic assumptions), and make explicit agreements about the nature and scope of the relationship.

- Acknowledging power differentials and differences.

- Committing to constructive processes and safe space to negotiate and resolve conflict.

- Ensuring fair distribution of resources, responsibilities, credit, and visibility.

- Establishing realistic time frames and expectations.

- Operating with complete transparency.

- Planning for and managing risk.

- Balancing structure with flexibility and agility.

- Successful alliances pay attention to the details, devoting time to negotiating explicit agreements on the purpose of the alliance and how it will operate, specifically:

- Goals, objectives, and outcomes.

- Roles and responsibilities.

- The nature of the alliance (e.g., short- or long-term, strategic or tactical, formal or informal).

- Decision making.

- Funding, i.e., if and how the alliance will seek funding, how funding decisions are made, how funding is distributed, when and how to engage donors.

- Resources, i.e., who will contribute staff time, office space, expenses, etc.

- Spokespeople, i.e., who can speak on behalf of the entire alliance, in what context(s), and when.

- Communication, e.g., how often will the alliance meet/share information, how quickly should individual members report back on activities or progress, etc.

Tools for Choosing Allies & Building Solidarity

ON-THE-GROUND CONVERSATION…

Hear Shereen Essof, Maria Mustika, Sophorn Yit, Jojo Guan, Osang Langara, Paty Ardón and Valerie Miller talk about choosing allies and building solidarity, and share thoughts on how the power of solidarity and alliances makes us stronger, safer and bolder.

-

Osang: My starkest realization was that women in other countries suffer almost the same injustices as women in my own country [the Philippines]. This realization prompted me to seek more ways to forge ties with other countries from different regions, in order to strengthen the impact of our advocates and to build bridges for different forms of exchanges and alliances in the future.

-

Paty: We need our alliances because our strength is limited, and it is in alliances that we can have a greater impact. If we work in alliances -- from the smallest scale to alliances with others who are facing and fighting for the same changes in different parts of the world -- we have a much greater possibility of moving forward.

Paty: We need our alliances because our strength is limited, and it is in alliances that we can have a greater impact. If we work in alliances -- from the smallest scale to alliances with others who are facing and fighting for the same changes in different parts of the world -- we have a much greater possibility of moving forward. -

Shereen: If we can activate alliances with unexpected partners, there is a lot of energy in that. In our work in Southern Africa, power comes about from creative and unusual partnerships. We bring together sexual and reproductive health rights activists, religious leaders, HIV positive women activists and dynamic communicators to maximize the impact of our work. If you’re able to traverse all of that—contradictions and complexities—in order to do work, it’s powerful.

-

Maria: Through JASS, I learned that I am not alone—I have so many sisters, and suddenly all of their problems become mine and mine become theirs. When an activist friend of ours was jailed because the government was trying to silence her, it became all our fight, and our voices together got her released.

Maria: Through JASS, I learned that I am not alone—I have so many sisters, and suddenly all of their problems become mine and mine become theirs. When an activist friend of ours was jailed because the government was trying to silence her, it became all our fight, and our voices together got her released. -

Sophorn: Standing up as a feminist activist in Cambodia is not easy. But with inspiring women who are not afraid to stand up for what they believe is right—it can be done. Together we rise in solidarity!

-

Valerie: How do you explain the magic of JASS’s Alquimia Leadership and Training School? The School provides truly miraculous moments of collaboration, creativity and critical inquiry—all focused on building and strengthening women activists and their movements for justice. Add some good music, dancing, singing and a few bad jokes and—abracadabra—wonderful synergy and solidarity.

Valerie: How do you explain the magic of JASS’s Alquimia Leadership and Training School? The School provides truly miraculous moments of collaboration, creativity and critical inquiry—all focused on building and strengthening women activists and their movements for justice. Add some good music, dancing, singing and a few bad jokes and—abracadabra—wonderful synergy and solidarity. -

Jojo: The most important thing is to keep building our solidarity with each other. That's a source of our power.

-

Patricia: Solidarity in our struggles is fundamental. It is the glue that unites us in a deep way that goes beyond one-off support or a single project. It is the relationship that unites us to face the system under which we live and to confront its impacts. It also unites us to be able to strengthen ourselves and continue to build and reinforce the fabric of life among all.

Patricia: Solidarity in our struggles is fundamental. It is the glue that unites us in a deep way that goes beyond one-off support or a single project. It is the relationship that unites us to face the system under which we live and to confront its impacts. It also unites us to be able to strengthen ourselves and continue to build and reinforce the fabric of life among all.

- Choose your allies carefully. To evaluate your potential allies, your organization should have a prior relationship and trust built on direct experience and effective communication over time. Building that trust will continue to be a long-term, ongoing process.

-

“When feminism does not explicitly oppose racism, and when antiracism does not incorporate opposition to patriarchy, race and gender politics often end up being antagonistic to each other and both interests lose.”—Kimberley Williams Crenshaw Navigating Difference & Building Political Trust

Navigating Difference and Building Political Trust is a critical ingredient for forming strong organizations and alliances.

To build a sufficiently powerful force to challenge inequality and violence, we have to come together across many divides. Yet, while shared identity and common circumstances can connect us, there are many stresses and fault lines that can divide us and prevent us from seeing each other’s common humanity. Ultimately, we need to build relationships and trust across differences. Creating new connections and identifying shared goals is essential to harnessing the power and potential of working together. And because conflict is inevitable, we need to find ways to address it directly and use it to build understanding and trust.

+ Read MoreWe must deal honestly with our differences in identity, position and privilege (e.g. race, gender, ethnicity, class, age, sexuality, ability), and with the conflicts that occur when those differences are not acknowledged and responded to openly.

"Privilege is when you think something is not a problem because it’s not a problem to you personally.”—David Gaider

Conflict is an inevitable part of forging common ground and collaboration across different people, issues, circumstances, movements, and organizations. Discord among organizations working together often arises in relationship to four big issues: resources (funding, time, expertise, opportunities), visibility (who gets credit), decision-making, and values. Dealing with these transparently and proactively, creating agreements and clear processes, can help avoid some conflict and build the trust necessary for navigating challenges together. Rather than avoiding or ignoring conflict, it is important to create processes within organizations and among allies to name and address the conflict directly, including creating safe spaces for tough negotiations and structured dialogues. Normalizing critical feedback and practicing open communication are essential for political trust to flourish. It will not grow if there are un-named conflicts and questions about power, decision-making and resources under the surface.

Putting assumptions and fears on the table becomes a way to go beyond the limitations they can bring. JASS’ developed our Heart-Mind-Body approach to re-build connections and trust across organizations in Zimbabwe, a place torn apart by years of divisive, violent politics. By creating safe space and entering the conversation focused on how the political context affects each of us in our hearts, minds and bodies, people could break through assumptions and fears, and find unexpected common ground in shared personal experiences, the beginnings of trust. This approach has enabled greater collaboration between more mainstream women’s groups and more marginalized constituencies, such as LBTI women, women in informal settlements and sex workers.

Tools for Navigating Difference & Building Political Trust

ON-THE-GROUND CONVERSATION…

Hope Chigudu, Alda Facio, Mariela Arce, Dina Lumbantobing, Atila Roque and Patricia Ardón discuss approaches to building trust, particularly across lines of difference, and how to deal with distrust and conflict directly as a normal part of organizational life.

-

Atila: We really need to understand what it means to build trust. To build trust is a long-term process. There are no shortcuts. There is no formal model to replicate, there is always deep histories of organizations, feminist movements, and that’s one thing to acknowledge.

Atila: We really need to understand what it means to build trust. To build trust is a long-term process. There are no shortcuts. There is no formal model to replicate, there is always deep histories of organizations, feminist movements, and that’s one thing to acknowledge. -

Mariela: Trust is a process, a nonlinear construction -- you can have a lot of trust with many sisters, and suddenly you screw up, or something happens, and it collapses. Hence, you have to take care not only of the content of that trust, but also how it is developing. It’s like caring for a plant, you have to take care of it as a specific political purpose.

-

Patricia: There’s no recipe for building political trust. It’s a process that takes time, and it’s a process in which the discourse must be joined with the practice. It’s precisely in the practice and in the solidarity -- from the daily solidarity in difficult times to the construction of joint strategies -- that political trust is strengthened. But, above all, it’s from everyday practice.

Patricia: There’s no recipe for building political trust. It’s a process that takes time, and it’s a process in which the discourse must be joined with the practice. It’s precisely in the practice and in the solidarity -- from the daily solidarity in difficult times to the construction of joint strategies -- that political trust is strengthened. But, above all, it’s from everyday practice. -

Hope: Here is an example from our work in Malawi. Since building trust and confidentiality are critical, we ask the women to reflect on and answer this question, “If you had a secret that you wanted to share, what kind of person would you share it with?” We talk about the fact that life involves risk taking and we have to learn to take risks and to trust if we are to build a movement. At the end of the discussion, the women agreed that to share a secret, a person should be trustworthy, honest, non-judgmental, patient, caring, respectful, and understanding. We were all asked to embrace these qualities, and be the kind of person we would confide in.

-

Mariela: Political trust is a strategic political product. Therefore, it is necessary to take care of the ways in which that work is being done and its content and results. One of the main ways of doing so is by maintaining transparency in everything that is going to be done together, and in the mindsets and differences, in order to be able to negotiate with modesty and integrity. Back and forth communication plays a key role.

Mariela: Political trust is a strategic political product. Therefore, it is necessary to take care of the ways in which that work is being done and its content and results. One of the main ways of doing so is by maintaining transparency in everything that is going to be done together, and in the mindsets and differences, in order to be able to negotiate with modesty and integrity. Back and forth communication plays a key role. -

Patricia: In order to face or address the differences and conflicts that we have among women, we have to recognize the different contributions made by different women, by different organizations and movements to develop the struggle for life, for the fabric of life, and for a different world. This individual acknowledgment and affirmation of the contributions of women is a basic foundation for building trust and for being able to address our differences in a more constructive way, as is the recognition of the different types of knowledge and skills that we women have.

-

Hope: Conflict can arise at any time. During our discussions in Malawi, there started to be gossip accusing some women and sex workers of being "bad women" because they do not behave like "good women" are supposed to. We used that as a learning moment. We paused and engaged in a conversation on what it really means to be a "good" woman? How easy is it for any woman to live up to society’s expectations? Who has the power to set these expectations? Should women strive to meet these expectations, even when they are oppressive and limit them from realizing their full potential? How do sex workers perceive themselves? We made it clear that if we continue to divide women into good and bad, we shall not move together as women fighting for the same thing. A movement can’t be built on stereotypes.

Hope: Conflict can arise at any time. During our discussions in Malawi, there started to be gossip accusing some women and sex workers of being "bad women" because they do not behave like "good women" are supposed to. We used that as a learning moment. We paused and engaged in a conversation on what it really means to be a "good" woman? How easy is it for any woman to live up to society’s expectations? Who has the power to set these expectations? Should women strive to meet these expectations, even when they are oppressive and limit them from realizing their full potential? How do sex workers perceive themselves? We made it clear that if we continue to divide women into good and bad, we shall not move together as women fighting for the same thing. A movement can’t be built on stereotypes. -

Mariela: To navigate between difference and conflict in a constructive way, I think that egos must be left behind. That implies a level of maturity, of recognition of the contribution of each person, of respect, and -- above all -- of having a clear sense of the common good as a priority. In the face of any difference and conflict, the collective highest good must prevail. And right now, we are at a level of so much risk and danger of reversal that it is totally absurd to overestimate the differences. I believe that the highest common good is above any difference, above any conflict.

-

Dina: To address conflict in a constructive manner, we need to constantly remind ourselves of our shared vision and a belief that in any kind of conflict, all should keep in mind why we all fight together and promise to not allow anyone to interfere with the struggle. I also try to develop space in which everyone can speak openly about their concerns and problems that potentially create conflict.

Dina: To address conflict in a constructive manner, we need to constantly remind ourselves of our shared vision and a belief that in any kind of conflict, all should keep in mind why we all fight together and promise to not allow anyone to interfere with the struggle. I also try to develop space in which everyone can speak openly about their concerns and problems that potentially create conflict. -

Alda: We also need to ensure that our movements are multi-generational. This is not simply about women of various ages being in the same movement. Partly, it is about building respectful relationships of trust, and of learning, and teaching based on a long-haul approach to movement building. But, as with other power relations, it is also about raising our awareness of age-power relations.

-

Mariela: When one is very involved in a conflict, it is very useful to ask for help, to ask external people that are not emotionally involved in the conflict to intervene and help untangle situations, and with this, move forward together.

Mariela: When one is very involved in a conflict, it is very useful to ask for help, to ask external people that are not emotionally involved in the conflict to intervene and help untangle situations, and with this, move forward together.

-

ON-THE-GROUND CONVERSATION…

In this conversation, Amina Doherty, Lisa VeneKlasen, Malena de Montis, Phumi Mtetwa, Vivi Marantika, Erma Wulandari and Linnah Matanya reflect on power and how understanding power fully, in all parts of our lives and in its ever-changing dynamics, is critical for activists to make an impact.