Standing Up: Mobilization, Alliances and Action

Are you ready to move into action—resisting, speaking out, challenging, proposing solutions and standing up for what you believe is right? Are you clear what tactics will take your agenda forward and preparing for potential risks or backlash? Do you need to define what change or alternatives solutions you are promoting? Do you want to change the public conversation and are you clear on your message, medium and audience? These Cycles can be used as a framework for Movement Builders—both experienced and new. So start collecting your tools and store them in your We Rise toolkit.

Standing Up is about organizing and mobilizing our collective power with others to resist injustice, challenge the status quo, stand up for our rights, address needs and assert our demands.

-

Mobilizing Our Power Together Mobilizing our collective power to amplify our voices, impact a specific problem and stand up for our rights, justice, freedom and dignity.

-

Shared Strategy and Tailored Tactics Clarifying our vision, goals and strategy together so we can choose creative and effective tactics for different moments. This enables us to make our needs and demands known, utilize or create political opportunities and build our power and impact over time.

-

Interconnected Movements Expanding the interconnectivity of many organizations and efforts ("meshworks")—cultural, social, political—to amplify our shared vision, values and agenda and to inspire aligned yet independent action, art and involvement.

-

Challenging and Changing the Public Conversation Getting our voices and ideas heard with communications and knowledge strategies that break through the dominant public narrative, raise social awareness, generate new ways of seeing issues and equip us to better influence debate and decision-makers.

-

Risk, Security and Community Analyzing the risks and power dynamics of our activism in context, and weaving local, regional and even global networks of support to protect our organizations and ourselves as activists.

-

Alliances, Conflict and Negotiation Building agreements and working through conflict inside our groups and within alliances; negotiating relationships with different kinds of political actors who have influence on the issues we care about.

-

“If you want to go fast, go alone. If you want to go far, go together.”—African Proverb; “When spider webs unite, they can tie up a lion.”—Ethiopian Proverb Mobilizing Our Power Together

Mobilizing Our Power Together is about rallying our collective power to amplify our voices and our social and political change agenda, and to stand up for our rights, justice, freedom and dignity. Our power lies in finding common ground among different interests to build collective strength. In Rising Up and Building Up we talked about creating the kinds of processes and deep conversations that bring people together and generate mutual support, solidarity, and recognition and respect for differences. This way, collaboration multiplies individual talents, knowledge and resources to make a larger impact. Collective power, what we call “power with”, provides a grounding sense of community and emotional/spiritual connection.

+ Read MoreMobilizing power with is about developing plans, tactics and strategies that tap into different types of knowledge and leadership, and affirming to ourselves and others that we are in this together.

“The unfulfilled promise of women’s equality cannot be realized without mobilizing the power of women’s voices, knowledge and numbers for sustained pressure and influence on policies, institutions and social norms. With growing backlash and violence today, organizing women is also about using women’s organizing power for self-defense, and for protecting activists and their organizations.” – JASS

JASS’ core mission—building women’s collective leadership and organized power—is based on the fact that women, who are most affected by the political, economic, environmental and health crises reverberating across the world, are also at the forefront of change in their communities. Though often invisible or portrayed as victims in the media, women bring solutions and play crucial roles in leading their communities to defend rights, fulfill needs, challenge excesses of power and promote long-term change—often at great personal risk. When women are better equipped, resourced and connected, they can play an even more vital and effective role in making political change that leads to real change in people’s lives. Mobilizing power with through grassroots organizing is the way we ensure that the people most affected participate and lead in movements for change.

Bottom-up advocacy and movement-building approaches not only amplify the reach of change strategies, they also ground our advocacy and lobbying efforts. Sustained popular action is key to closing the gap between policy commitments and implementation. Experience shows that good data and evidence, compelling media, and concrete policy proposals are key ingredients to political change, but without actions that activate and show the strength of well-organized constituencies—particularly those most affected by the unresolved problems—powerbrokers are less likely to move. In recent years, mass mobilizations on climate change, corruption, racist policing, and fees for education have made once-invisible issues headline news, placing them at the top of policy agendas and election campaigns.

It is tempting to design tactics and actions with a short-term perspective aimed at what will make the biggest splash—what will go viral or hit the mainstream news. This can create a tension between “winning and building,” Sometimes, momentary, opportunistic thinking makes sense in a campaign, but it’s important to also consider how a particular action is part of a longer-term strategy to build connection and community and to mobilize collective power.

“While policy is critical, we need to broaden our understanding of winning so that winning and building are not at polar opposites. The vital link between them is a long-term vision.”—Jojo Geronimo, Making Change Happen 3: Power

In any given action or activity, we have an array of roles and leadership opportunities available. Constituents can get involved in research and information dissemination to make a case, or they can participate in learning and leadership opportunities associated with outreach, community education, media, etc. If we’re working in a hostile context, it’s important for mobilization strategies to include information and analysis of context, urgent action plans, social media alerts and self-protection mechanisms that maximize the safety of everyone involved, on all levels. Building collective power depends on uniting strengths, but it also depends on respect and taking care of each other to be sustainable and reflect the world we are building.

Tools for Mobilizing Our Power Together

-

Shereen: Our work is to build from the ‘I’ to the ‘we.’ It’s about thinking of how to connect women to each other and to connect to a broader feminist strategy at the local, national, regional and global levels.

-

Sibongile: Power with has to do with finding common ground among different interests and people in order to build collective power, so that we are able to transform power and bring forward the change we want. This is done based on mutual support and solidarity that connects people, the collaboration between women, and the recognition and respect for our differences. Power with can also help build bridges across different people by openly acknowledging conflicts, and seeking to transform these for a greater end.

Sibongile: Power with has to do with finding common ground among different interests and people in order to build collective power, so that we are able to transform power and bring forward the change we want. This is done based on mutual support and solidarity that connects people, the collaboration between women, and the recognition and respect for our differences. Power with can also help build bridges across different people by openly acknowledging conflicts, and seeking to transform these for a greater end. -

Daysi: Power with others is the basis of the power to bring about change. It involves not only the sum of the individual parts or powers but also building and imagining things that have not been built and tackling situations that we had not been able to tackle before. From power with emerges creativity, not as an individual experience, but as an encompassing experience that can respond to the different realities that we face as diverse persons. Power with others recognizes that only multiverse – rather than universal—realities can be generated, with as many alternatives as there are persons, but that alternatives can also be generated in which the thought, vision, desire and utopia of others converge.

-

Amina: Crossing the line is a collective moving forward; it is a stampede. It is all women finding the strength to claim our power.

Amina: Crossing the line is a collective moving forward; it is a stampede. It is all women finding the strength to claim our power. -

Sibongile: When women feel safe and feel that they have power with others and that they are not alone, they open up and build together, they organize together, and they transform and change together.

-

Kwangu: We decided to use our collective power to do something to ensure that the women in the traditional authority were able to access their HIV treatment. At first, we talked to the health personnel but they would not cooperate. We then went to the Honorable Member of Parliament. He immediately called the person in charge of the clinic and demanded that the clinic be opened and all the people accessed ARVs on that day.

Kwangu: We decided to use our collective power to do something to ensure that the women in the traditional authority were able to access their HIV treatment. At first, we talked to the health personnel but they would not cooperate. We then went to the Honorable Member of Parliament. He immediately called the person in charge of the clinic and demanded that the clinic be opened and all the people accessed ARVs on that day. -

Dorica: We need to know that we have power within ourselves, that we have rights. And, we have to advocate for change that is right for us. Women have the power within themselves, but alone, we can’t make big changes. We can come together to do something great.

-

Tiwonge: I now know that I have power within myself, and power with others too, and that I can transform my individual power into a collective power to drive change in my family, community and nation.

Tiwonge: I now know that I have power within myself, and power with others too, and that I can transform my individual power into a collective power to drive change in my family, community and nation. -

Lisa: The mobilization in response to the murder of Berta Caceres very quickly became a global solidarity movement. We have a set of demands and principles based on the experience of COPINH and the Hondurans on the ground. That is what really makes the ¡Berta Vive! movement so strong; it continues to respond to and be anchored by those who are most affected by the injustice that we are mobilizing against. Our specific demands are really shaped by their demands.

-

Daysi: When the coup in Honduras happened, we were there. We were on the streets, and everyone was coming out—it was really chaos! And then when we started to shape it a little bit, this Resistencia. Actually, we called ourselves “Feminists in Resistance”. For the first time, feminists were in the front-line leadership. Solidarity enabled us to be as visible and as strong as we were, because we had built solidarity outside Honduras. And it was visible solidarity, it was rapid-response solidarity, and it was solidarity built on trust. The other social movements, they didn’t have that.

Daysi: When the coup in Honduras happened, we were there. We were on the streets, and everyone was coming out—it was really chaos! And then when we started to shape it a little bit, this Resistencia. Actually, we called ourselves “Feminists in Resistance”. For the first time, feminists were in the front-line leadership. Solidarity enabled us to be as visible and as strong as we were, because we had built solidarity outside Honduras. And it was visible solidarity, it was rapid-response solidarity, and it was solidarity built on trust. The other social movements, they didn’t have that. -

Sibongile: Power with is really important in building movements, because it creates safe space for dialogue, consciousness raising, and capacity building, increasing women's power as citizens, as well as their capacity to critically analyze the context and come up with their own solutions and how to work on them.

-

-

“Start the process of strategy development by imagining that instant just before victory. Then, working backwards, do your best to figure out the steps that will lead to that moment.”—Si Khan, activist and popular educator Shared Strategy and Tailored Tactics

Shared Strategy and Tailored Tactics is about defining our vision, goals and strategy together so we can choose creative and effective tactics for different moments. This enables us to make our needs and demands known, utilize or create political opportunities and build our power and impact over time. When groups organize for change, they determine what change they want, including a longer-term vision and related interim goals; and their strategy—what they believe they need to do to bring about that change.

+ Read MoreGood strategy grows out of a clear power analysis and understanding of the context: who are the decision-makers, who are the key players involved –both out front and behind-the-scenes–, who are our potential allies, what are the ideas and beliefs that are shaping public opinion on the issue, what capacity does the organization with its allies have in terms of organized base and other resources and what are the particular openings or opportunities in the current moment? This analysis informs a guiding strategy or strategies. Tactics are how we act on our strategy in a given moment and they always change over time.

We’ve found that there is often confusion between tactics and strategy. Strategy is the bigger-picture plan of how we want to bring about change; tactics are the specific way we act to advance that strategy in a given moment. Strategies tend to have a longer life, guiding our work over periods of time. They might include: to build a strong cross-movement alliance, to hold key decision-makers accountable or to change the social norms or public opinion on a key issue. Tactics are always changing with changing contexts and power dynamics. At one moment, a direct action or protest might make sense. At another, a social media campaign challenging the dominant story will work. At another, participatory research that gathers key data and builds community involvement is the best approach. And at a certain point intensive political education and alliance building is the best course of action. We have to tailor the tactics to the context, opportunities and capacities with which we are working.

Since most organizing efforts require working with allies both inside and outside the decision-making process, a shared strategy harnesses the different capacities of each one and guides their efforts toward the same goal. Sometimes allies share tactics, and sometimes they differ, each ally playing different roles—for instance, one protesting in the streets, one advocating within the government. If there is an overall agreement on goals and strategy, these converging tactics can create a powerful impact.

Developing shared strategy within an organization and with allies grows out of a shared analysis of the context. Generally, organizations find they need a multi-faceted process that defines their goals for change and rigorously maps power dynamics that will affect achieving that goal. It is important to have a sense of what the longer-term goals are, how we strategically pursue those over time (e.g., gaining labor protections for women, ending oil extraction in our communities) and what immediate goals and tactics will move us forward (e.g., building a women’s union, holding community hearings on the impact of the oil wells on the community, protesting government policies or corporate violations).

Tools for Shared Strategy and Tailored Tactics

ON-THE-GROUND CONVERSATION…

Listen in to Joanne Sandler, Amina Doherty, Anna Davies-van Es, Daysi Flores, Malena de Montis, Zephanie Repollo and Patricia Ardon reflect on how they think about and devise overarching strategies and tailor effective tactics in women’s organizing work.

-

Zephanie: When people start identifying their issues as similar and shared with others, you can form that unity amongst different groups. It can be common rage, it can be common grief or it can be something they commonly value and love, and identifying that can surface a shared strategy.

-

Joanne: Who knows better than the people who are directly affected the kinds of policies that are needed to either accelerate or prevent certain things from happening? When organizing involves working with local communities, it allows people to undertake their own systems’ analysis, thus leading them to become influential policy actors by proposing policies.

Joanne: Who knows better than the people who are directly affected the kinds of policies that are needed to either accelerate or prevent certain things from happening? When organizing involves working with local communities, it allows people to undertake their own systems’ analysis, thus leading them to become influential policy actors by proposing policies. -

Zephanie: Shared strategy can also come with shared context and realizing that the different issues they’re bringing forward are actually reinforced by the same structural systems of oppression. I think that’s important for deepening understanding and for interrogating power on different levels. It invites conversation, to uncover underlying power, and that can go way back to colonial times and how we enforce that in the present and how patriarchy reinforces policies and militarization in different phases. These are the entry points of unity, and shared hopes and shared dreams can move people to work together.

-

Anna: The Our Bodies Our Lives campaign has been doing an ongoing power analysis and supporting strategy based on that power analysis. Part of that is about assessing the political moment, and so sometimes, the inside strategy has been important in engaging and working directly with the Ministry of Health. However, I can imagine another time in a shifting political terrain where that would not be possible, or not desirable for the campaign, because the demands may come in conflict with the political priorities of the ministry or of the government more broadly.

Anna: The Our Bodies Our Lives campaign has been doing an ongoing power analysis and supporting strategy based on that power analysis. Part of that is about assessing the political moment, and so sometimes, the inside strategy has been important in engaging and working directly with the Ministry of Health. However, I can imagine another time in a shifting political terrain where that would not be possible, or not desirable for the campaign, because the demands may come in conflict with the political priorities of the ministry or of the government more broadly. -

Malena: We did a contextual analysis and saw that the impact of imperialism, the ongoing impunity, corruption, violence, and everything had a greater impact on women; but, why focus our work with indigenous women? Because we figured out that they were at the heart of the building resistance that was already underway.

-

Patricia: We analyzed in greater depth the situation of women who were struggling for their territory and natural resources, something that hadn’t been thought about much at that time. There was a very important gap in some contexts between feminists and indigenous and rural women in their struggles regarding their immediate demands, more closely linked to their most pressing needs. So at that point, we saw ourselves as an organization that could contribute to building bridges between organizations, but also at a level of knowledge.

Patricia: We analyzed in greater depth the situation of women who were struggling for their territory and natural resources, something that hadn’t been thought about much at that time. There was a very important gap in some contexts between feminists and indigenous and rural women in their struggles regarding their immediate demands, more closely linked to their most pressing needs. So at that point, we saw ourselves as an organization that could contribute to building bridges between organizations, but also at a level of knowledge. -

Daysi: After the 2009 Honduran Coup d'etat, during the whole mobilization process, we as feminists gathered after every demonstration and we’d assess because things changed from one day to another. It was 7 months, but it felt like 7 years because everything was so different and every single day was kind of a year of decisions and assessing and strategizing.

-

Amina: It’s important for activists to do some deep thinking around the context in which they work, and to understand that safety and security, for example, is something they need to prioritize. Given the context of safety and security, strategies like public marches or even posting things on social media might be one that works in one context, and one that others would find really challenging.

Amina: It’s important for activists to do some deep thinking around the context in which they work, and to understand that safety and security, for example, is something they need to prioritize. Given the context of safety and security, strategies like public marches or even posting things on social media might be one that works in one context, and one that others would find really challenging.

-

-

“There can be no peace without justice and no justice without human rights and no human rights without women’s rights and no women’s rights without feminist and women’s movements.”—Alda Facio, Costa Rica Interconnected Movements

“There is no thing as a single-issue struggle because we do not live single-issue lives.”—Audre Lorde

Interconnected Movements is about building the interconnectivity among many organizations and social justice efforts who share similar visions of change—cultural, social, economic, political and ecological. Also referred to as “big tent” or intersectional organizing, the aim of Interconnected Movements is to link our diverse efforts into a much larger, loosely coordinated political force. This force amplifies the transformational power of our organizing and movements, while also allowing for the possibility of independent action, art and involvement by many different people.

+ Read More“The reason [why] movements matter is [because of] their capacity to create sustained change at levels that policy change alone cannot reach.” —Srilatha Batliwala

In recent years, climate change has become a globally-recognized crisis. Its scope forces us to recognize how interconnected our specific issues are and how critical it is to join forces with others to be a more effective force to impact those who hold the most power and influence. Since the roots of climate change lie in failed economic and political choices that benefit only a few corporations, elites and governments—and since the changes in climate hit poor and marginalized communities more than others—we can see the importance of joining together and building broader movements for change.

“What if we realized that real disaster response means fighting inequality and building a just economy; that everyone working for a healthy food system is already a climate warrior? So too are people fighting for public transit in Brazil, housing and immigrant rights in the US. There are movements battling austerity in Europe, extraction in Australia, pollution in China and India, environmental crime in Africa and the bad trade deals that lock in all of these ills everywhere. I believe the movement we need is already in the streets, in the courts, in the classrooms, even in the halls of power. We just need to find each other. One way or another, everything is going to change. And for a brief time, the nature of that change is still up to us.”—Naomi Klein, This Changes Everything

Women’s leadership and struggles and feminist agendas are central to a broader economic, political and social movements for change, because if we do not fundamentally change social hierarchies we will not fundamentally change our institutions of exploitation and control. These hierarchies are propped up by traditional gender roles, learned domination, subordination and violence, which express themselves in our families, our organizations and society as a whole.

Interconnecting runs deeper than just building cross-issue and cross-movement agendas and alliances. It also means ensuring that community leaders and activists, particularly those most directly affected by the problems we are confronting, are central to the agenda-setting and public face of our efforts. It requires an integral analysis that clearly shows the connections and a shared strategy that assures that interconnectedness strengthens all the movements, rather than dividing attention or diluting focus.

Interconnectedness encompasses the horizontal linkage of like-minded movements and organizations, and it also includes linking up across borders and from the local to the global and vice versa. Again, climate change is an urgent case of the need to view the global and local simultaneously, but there are many others: Education crises, violence against activists, pollution, migration and exploitation and labor violations all have local, national and global root causes. Interconnection crosscuts issues, geographies, identities and socio-cultural contexts.

“Movements take shape over many actions, and over many moments where demands and issues are brought to the floor. Movements are not single-issue.”—Lisa VeneKlasen

Movements are built and activated in a variety of ways, depending on the context, timing, rallying points and the constituencies. They often start off with people who are linked to organizations or informal networks that organize around a particular issue or set of issues. They then attract and seek out more individuals and organization allies to increase their influence and reach. At that point, they very deliberately begin to build what is often referred to as “movement infrastructure”—a loose set of processes, planning, communication and decision-making points that enable a diverse, interconnected and flexible web of activists, alliances, networks and organizations to define their shared agenda, stay connected and mobilize actions. Throughout this process, those involved regularly negotiate various roles, divisions of labor, approaches, resources, tactics and strategies in order to transform power dynamics and advance deep social change.

In building and connecting distinct issues and movements, mutual respect and solidarity are crucial. In addition, there is a need for continuous conversations between leaders, organizers, communities and constituencies.

Our work with HIV+ women activists fighting for quality medicines, for example, began with frequent gatherings among women involved in informal networks. These group-building and agenda-surfacing processes created space for women to engage in political analysis and unpack the root causes of poverty, HIV and the many other challenges in their lives. The common ground we found became the basis for distinct groups and networks operating in different communities to remain connected. Over time, key leaders came together to formalize and expand their network with various organizational allies. This became the foundation for forming a network and launching a nationwide campaign—Our Bodies, Our Lives: The Fight for Quality ARVs (Antiretrovirals). Going forward, in an effort to take the campaign to the next level and to take on some of the global policy and corporate actors who have a direct impact on HIV and related medicines, JASS and our allies will seek the involvement of more institutions to advance the conversation and increase the clarity and the power of the movement’s demands.

In another example, the assassination of Berta Caceres, feminist indigenous and environmental leader, brought the crisis of corruption, impunity, violence and militarization in Honduras to international attention. Berta’s organization, the Civic Council of Popular and Indigenous Organizations of Honduras (COPINH), and its allies in Honduras have put forward clear demands and anchored a loosely connected set of social justice activists, human rights organizations, indigenous people’s networks, environmental groups and feminists. Through distinct actions based on the demands of the communities and organizations most affected, they have succeeded in persuading the Dutch and Finnish investors to suspend their financing for the construction of the dam that Berta was killed for opposing. In addition, US Congress members have introduced legislation to suspend US military and security aid to Honduras, and human rights groups are pushing for the creation of an independent expert commission with the Inter-American Human Rights Commission to investigate Berta’s murder. Many international organizations working on different issues and in different places have converged into the #Justice4Berta movement and, in so doing, have kept environmental, human rights and many other issues at play on the global agenda.

Tools for Interconnected Movements

ON-THE-GROUND CONVERSATION…

Hear what Kunthea Chan, Lisa VeneKlasen, Patricia Ardon, Daysi Flores and Everjoice Win have to say about how movements are built on connections.

-

Kunthea: To make a movement effective, we need to leverage our collective power through organizing. Organizing to me is not simply working alongside people within the same organization, but rather, collaborating with women in various sectors and movements and looking past our differences to find common ground as women activists.

Kunthea: To make a movement effective, we need to leverage our collective power through organizing. Organizing to me is not simply working alongside people within the same organization, but rather, collaborating with women in various sectors and movements and looking past our differences to find common ground as women activists. -

Everjoice: If anyone was ever in doubt about the power of MOVEMENTS, one has to simply look at the enduring appeal, mobilization and organizational capacities of the ANC (African National Congress), FRELIMO (The Mozambique Liberation Front), ZANU (Zimbabwe African National Union) or SWAPO (South West Africa People's Organization), and learn from them. Love them or hate them, the liberation movements speak to the HEARTS (as opposed to heads), of a sizeable number of citizens in their countries. Their messages still reverberate and resonate quite well even beyond their national borders.

-

Lisa: Movements cannot exist without a movement culture. Movements are not two or three organizations working together. They are more than that. Black Lives Matter has emerged as a movement through many actions which share a deep understanding of race, class, and gender in America. Though the focus initially was on the criminal justice system, the Movement for Black Lives (M4BL) has grown and expanded its calls for justice in housing, education, cultural institutions and the media. Essentially, it examines all aspects of what it is to be a person of color in America. It is now building a movement consisting of many different organizations working together around shared goals and a shared vision.

Lisa: Movements cannot exist without a movement culture. Movements are not two or three organizations working together. They are more than that. Black Lives Matter has emerged as a movement through many actions which share a deep understanding of race, class, and gender in America. Though the focus initially was on the criminal justice system, the Movement for Black Lives (M4BL) has grown and expanded its calls for justice in housing, education, cultural institutions and the media. Essentially, it examines all aspects of what it is to be a person of color in America. It is now building a movement consisting of many different organizations working together around shared goals and a shared vision. -

Daysi: One of things that we stressed a lot was the fact that we women make up half of the world and half of heaven, so we are half of everything, of all struggles and movements. Patriarchy is a cross-cutting matter, in other words, patriarchy involves abuse of power and the abuse of power at home runs parallel to the abuse of power within the state.

-

Lisa: With all the investment in advocacy, it’s easy for many to confuse or conflate coalitions working on policy issues with movements. They are not the same. While a policy agenda is important, movements are more than that. Similarly, we confuse virtual campaigns—hashtags and slogans—with movements. They too are important in getting new ideas and problems into the public conversation, but they’re not movements. Movement organizing both includes and goes beyond policy and social media—it is rooted in communities and different contexts through organizing and building connections.

Lisa: With all the investment in advocacy, it’s easy for many to confuse or conflate coalitions working on policy issues with movements. They are not the same. While a policy agenda is important, movements are more than that. Similarly, we confuse virtual campaigns—hashtags and slogans—with movements. They too are important in getting new ideas and problems into the public conversation, but they’re not movements. Movement organizing both includes and goes beyond policy and social media—it is rooted in communities and different contexts through organizing and building connections. -

Patricia: Collective power is built by recognizing the different contributions that different people and collective groups can make to increase the ability to catalyze the common interests of the people and the communities, commit to the people’s causes and desire for change, and refine political clarity about the forces that movements face--how they operate, who they are, what are the dynamics of their relationships. This enables us to create strategies on the basis of a wider and deeper analysis and greater clarity about the change we seek.

-

-

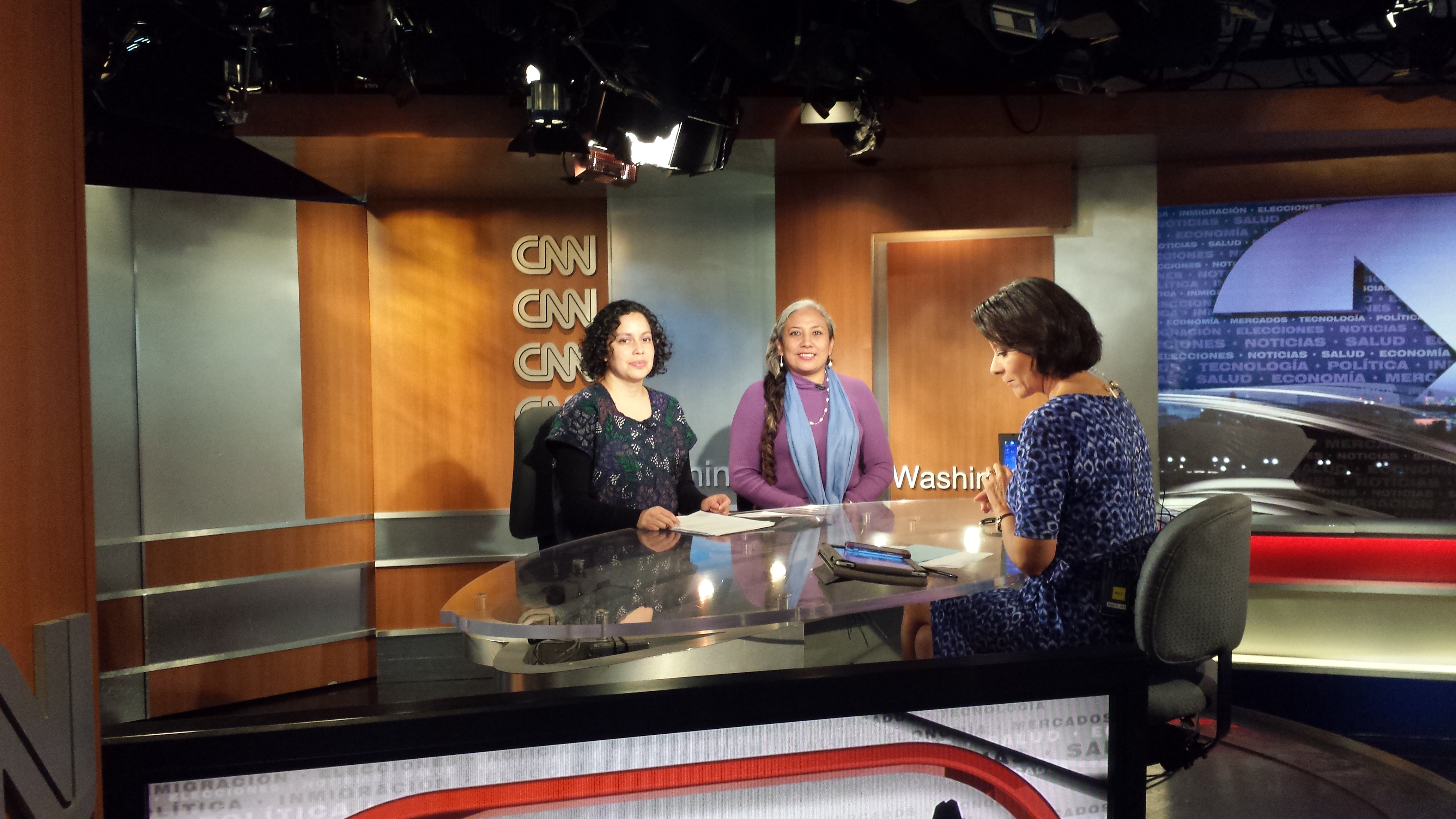

“Interrupting the public conversation involves finding creative ways to challenge the narratives that make us and our issues invisible and reinforce oppression. It is the deliberate quest to include diverse perspectives in public dialogue."—Alexa Bradley Challenging and Changing the Public Conversation

Challenging and Changing the Public Conversation means getting our voices and ideas heard and perceived as a legitimate part of the public conversation. It means changing what’s being talked about, how issues are understood and whose perspectives are valued. Communications and knowledge production strategies, including the use of creative tools, cultural media and visible spokespeople, can break through the dominant narrative to raise social awareness, invite new ways of seeing issues, introduce our demands, and influence debate and decision-makers.

+ Read MoreInterrupting the public conversation is a vital part of any change process. Dominant narratives - like all forms of invisible power - shape how we see the world and influence our sense of self, often even when those narratives go against our own lived experience and verifiable facts. We cannot shift the biases, beliefs and norms that legitimize inequity and exclusion without challenging dominant narratives.

We can all think of examples of dominant narratives which reinforce existing power relationships and the status quo: ‘climate change is unproven’, ‘activists are troublemakers or even terrorists’, ‘women can’t lead and can’t be trusted’, ‘governments can’t deliver social services’, ‘extractive industries are vital to development,’ ‘bad women get what they deserve”’, and ‘immigrants threaten our jobs and way of life,”. Although these statements are false, powerful interests are deeply invested in promoting belief in them to protect their privilege.

If we focus our attention solely on policy reforms, we overlook a key strategic element that could undermine our success - shifting the assumptions or social norms that validate these policies. Socialization, culture and ideology perpetuate exclusion and inequality by defining what is normal, and determining what is “right”, “true” and acceptable.

Those who control the dominant narrative operate as gatekeepers who can block significant issues and ideas from reaching the decision-making table. They seek to prevent them from entering the minds and consciousness of members of society, even those directly affected by a particular problem, and to normalize conditions of poverty, racism, sexism and corruption. The power to influence how individuals think about their place in the world, their beliefs, their acceptance of the status quo, and their understanding of their own value in society is formidable. Worse still, this form of invisible power often denies systematic discrimination or blames it on those who experience it.

Movements, therefore, need strategies to expose, interrupt and counter the invisible power that permeates social and political culture. Many social justice organizations use research, political education, creative actions and social media to unmask injustice and bring alternative values and worldviews to the public eye. Art, poetry, theater and music reach people and communities in ways that words do not. Organizing strategies strengthen critical thinking skills, to both challenge beliefs that keep people down and transform the way people perceive themselves and those around them, inviting visions of future possibilities and alternatives.

The actions and messages of Black Lives Matter are a great example of bringing the invisible into the public agenda. African-American communities have long faced police brutality and racist policing through excessive force, but the combination of a provocative and simple hashtag, community demonstrations, cellphone footage of abuse, strategic use of symbols and alliances, along with sustained organizing, have brought deepened awareness and changed the public conversation in the US and around the world.

JASS has worked with many allies over the past seven years to shift the dominant narrative on women activists and their needs, often invisibilized or overlooked in human rights discussions. Specifically, we have sought to increase the understanding of their leadership contributions and the recognition of the specific forms of violence they face both for their activism (by their opponents), and for stepping out of typical gender roles (in their families, communities and organizations). We have supported organized networks that bring visibility to women human rights defenders’ (WHRDs) demands, published analysis, shared interviews with the activists themselves, amplified their stories and supported WHRDs in directly participating in regional and global advocacy spaces to make their perspectives known. We now are seeing a greater acknowledgement of women activists’ needs and support for their work in UN, donor and NGO circles.

Tools for Challenging and Changing the Public Conversation

ON-THE-GROUND CONVERSATION…

In this conversation, Kunthea Chan, Zephanie Repollo, Patricia Ardon, Amina Doherty, Alexa Bradley, and Adelaide Mazwarira discuss how changing the political conversation creates space for other, more liberating ideas to be taken seriously and different solutions to be put on the table.

-

Amina: Creating change first requires recognition that society’s structures and institutional practices are unequal and unfair for many people. I see art and creative expression as a really important way to shape social norms, and here at JASS we call that the Hearts and Minds approach.

-

Zephanie: In the Philippines, women human rights defenders use creativity in street actions and protest. They’re using music to challenge the public conversation and raise awareness in public discourse and challenging practices and narratives that marginalize them. Embodiment, arts, music and storytelling are powerful tools in changing the narrative and women have so much to offer on that. Look at how resistance strategies in Thailand and Myanmar have used the Hunger Games salute as a cultural reference point to critique military regimes.

Zephanie: In the Philippines, women human rights defenders use creativity in street actions and protest. They’re using music to challenge the public conversation and raise awareness in public discourse and challenging practices and narratives that marginalize them. Embodiment, arts, music and storytelling are powerful tools in changing the narrative and women have so much to offer on that. Look at how resistance strategies in Thailand and Myanmar have used the Hunger Games salute as a cultural reference point to critique military regimes. -

Kunthea: We use movements to change our society, and JASS understands that key changes within the population require changing attitudes and norms. For instance, our workshops in Cambodia catalyzed changes in the way these activists think about themselves and their strategies so that they now pay more attention to safety and protection.

-

Patricia: I think there have been changes that many times aren’t visible, like there are fellow men in our struggles who have also come to support women’s causes as part of peoples’ causes–not that many, but there are a few. But I think that in general, movements for land and territory and indigenous peoples’ movements in many regions of the world, and in Latin America in particular, are very important not only in defending their rights, but also in proposing a shift of paradigm in terms of relationships between human beings and nature. And this can touch norms that are very accentuated in our societies.

Patricia: I think there have been changes that many times aren’t visible, like there are fellow men in our struggles who have also come to support women’s causes as part of peoples’ causes–not that many, but there are a few. But I think that in general, movements for land and territory and indigenous peoples’ movements in many regions of the world, and in Latin America in particular, are very important not only in defending their rights, but also in proposing a shift of paradigm in terms of relationships between human beings and nature. And this can touch norms that are very accentuated in our societies. -

Alexa: It is important to say we are talking about a form of power—invisible power—the dominance of certain ideas, norms and beliefs to the exclusion of others, that are used to legitimize the current reality. If we want to change that reality, we have to change the political conversation, and challenge the invisible power behind it., We may think it’s enough to say no to what we don’t like or disagree with. But, unless we’re actually re-framing the entire conversation and introducing a new lens to help people examine what is happening, the intervention is not enough. Changing the political narrative is a way of breaking through the denial about what is really going on, and putting forward a new way of seeing things.

-

Adelaide: Using the power of creativity and music and art are also powerful tools for raising awareness in the general public and bringing in new ways of seeing things, new voices, different possibilities.

Adelaide: Using the power of creativity and music and art are also powerful tools for raising awareness in the general public and bringing in new ways of seeing things, new voices, different possibilities.

-

-

Risk, Security and Community

Risk, Security and Community is about analyzing the risks and power dynamics of our activism in context, and weaving local, regional and even global networks of support to protect our organizations and ourselves as activists.

Women’s safety and security is a critical issue in all our work. In every region, the context we are confronting is violent, dangerous and volatile. Women face violence in multiple forms: state violence, backlash, gangs and organized crime groups, scarcity, poverty, vulnerability, sexual violence, natural disasters, fundamentalisms and hate.

+ Read MoreThe widespread violence severely affects the security of our movements. Governments lack the capacity and political will to protect and promote our rights. While we continue strategies of advocacy, much of our work is about pushing back against the tide and championing women’s resistance.

For JASS, a critical question is, “How do we ensure women’s freedom of expression and basic human rights in the face of a lethal mix of militarization and extremism that is closing the space for women’s activism and, in some instances, puts their lives at risk?” Across the regions in which we work, we have found similar patterns of oppression, corruption, impunity and violence perpetrated by both state and non-state actors. We have witnessed the impact of fundamentalism on stigma and discrimination. We have seen a rise in the criminalization of activists in the struggles over land and resources across Mexico, Central America and Indonesia. We have seen capitalist extractive industries target defenders. And we have observed state violence in Honduras, Guatemala, Myanmar and Zimbabwe, and repression in the fight for labor rights in Cambodia.

The scale and unpredictability of violence against activists, and women activists in particular, led JASS to reach out to close partners to explore how to create regionally relevant strategies for the protection of women defenders (WHRD). In 2010, we co-founded the Mesoamerican Women Human Rights Defenders Initiative. This unique cross-sectoral effort brings together women across many divides, including journalists, indigenous women defending territories, trade unionists, LGBTQI activists, mothers pursuing justice for family members and others. Today, many grassroots women leaders see themselves as human rights defenders for the first time, which enables them to better strategize and to seek protection. As a co-founder of this regional Initiative and of national networks in Honduras and Mexico, JASS Mesoamerica accompanies and supports women human rights defenders in dangerous situations through self-care techniques, protection mechanisms and risk analysis. Through these networks, JASS fosters coordination, solidarity and joint advocacy among activists within countries and across borders to strengthen their demand for justice and community control in development decisions.

In light of increasing levels of violence against women human rights defenders everywhere we work, JASS has shifted strategies to comprehensively and systematically assess and prevent risk, both in terms of our programs and our own operations. We have been able to translate the expertise developed by our work and team in Mesoamerica into increased skills, resources and awareness among all of JASS’ teams and among the diverse partners and constituencies with whom we work to manage fear, prevent harm and confront risk.

For example, greater awareness of the backlash and violence that women activists encounter when simply demanding their rights has led activists in Myanmar, Cambodia and Zambia to integrate security strategies in their programs. In Zimbabwe, where a long history of political instability and authoritarianism has made women's activism risky, JASS's partners have begun to dedicate resources to their safety and well-being, for example, organizing a training workshop on security protocols following the violence that ensued after the hotly contested 2013 elections. This training brought together influential organizations including the Katswe Sistahood, the Musasa Project, Gays and Lesbians of Zimbabwe, Women's Action Group and the Sexual Rights Centre. Building on this training, as well as more than two years of intense partnership with JASS Southern Africa, Katswe Sistahood adapted JASS's “Heart-Mind-Body” security and wellbeing strategy for their constituency of more than 800 women activists.

In violent contexts, our allies and our staff face risks. To that end, JASS has carried out risk assessments and developed security plans for each team, to ensure our safety and our ongoing ability to work in solidarity with our partners. We have made organizational changes, included a decision to register JASS in Mesoamerica and Southern Africa. We had previously avoided the measure to reflect our commitment to work with and through local and regional groups rather than creating formal institutions, but the scale of our operations and nature of our work presented challenges and risks that led us to legally register in these two regions. This provides greater access to resources and recourse in the places where we work, should JASS and/or its allies encounter major threats in the course of doing our work.

In 2015, using Mesoamerica as a model, JASS began participatory mapping processes in Southern Africa and Southeast Asia to understand the specific risks WHRD face, to analyze the contextual forces and actors behind those risks, and to identify existing resources and responses. This gives JASS and our allies a comprehensive picture of the situation and lays the groundwork for building networks for safety and urgent action.

Tools for Risk, Security and Community

ON-THE-GROUND CONVERSATION…

Women human rights defenders from Guatemala and Zimbabwe, Marusia Lopez Cruz, Maria Mustika, and Lisa VeneKlasen talk about how networks create the collective protection that activists need as they challenge injustice and face backlash.

-

Lisa: How do we at JASS protect and sustain the women and organizations on the frontline of real democracy-building, especially in the face of violence? What the women we work with want are networks—webs that are strong and vast and give them a sense of belonging, a source of collective power for change, and protection in the case of emergency.

Lisa: How do we at JASS protect and sustain the women and organizations on the frontline of real democracy-building, especially in the face of violence? What the women we work with want are networks—webs that are strong and vast and give them a sense of belonging, a source of collective power for change, and protection in the case of emergency. -

Amina: It’s important to do some deep-thinking and also to have mechanisms of support in place, so that if activists are being arrested, harassed or killed by the police, communities have mechanisms to support these activists in terms of financial support for bail and psycho-social support after experiences with the police and brutality.

-

WHRD from Zimbabwe: Our analysis has taught us that if we are in the business of dismantling power, something will come at us, and those things have the power to destabilize and destroy… We’ve tried hard to build ourselves as women human rights defenders, and to plan for safety and security. In the [safe] spaces that we build together, we laugh, cry, dance and rage, but we also strategize.

WHRD from Zimbabwe: Our analysis has taught us that if we are in the business of dismantling power, something will come at us, and those things have the power to destabilize and destroy… We’ve tried hard to build ourselves as women human rights defenders, and to plan for safety and security. In the [safe] spaces that we build together, we laugh, cry, dance and rage, but we also strategize. -

Marusia: Holistic feminist protection is a way of looking at protection for women human rights defenders that recognizes the gendered needs that we have as defenders, while acknowledging that we don’t live in a different reality than other women, that we have double and triple shifts, that we are discriminated against in our organizational spaces, and on the street, and in our lives, and thus we require protection measures that not only come to our aid in an emergency or specific situation, but also give us the necessary power, resources, and leadership to be able to create safer environments for our protection.

-

Maria: For me, the regional network in Indonesia—especially now because of fundamentalism and that our government is not cooperative with us on human rights issues – the regional network is becoming our safety net.

Maria: For me, the regional network in Indonesia—especially now because of fundamentalism and that our government is not cooperative with us on human rights issues – the regional network is becoming our safety net. -

Marusia: Self-care is a way for us to look at these needs, build wellbeing, and assimilate that we too, in our own lives, have to enjoy the rights that we struggle for and not feel guilty about it. We also have to realize that those movements that are concerned about the welfare of their people, their men and women, are movements that, first, do better work and, second, bring together more people who feel that these are spaces where one can truly live a different reality than the world of the rat race, exploitation, and violence.

-

WHRD from Guatemala: The search for justice after the murder of my father, along with my ongoing work defending human rights, led to a breakdown in my physical and mental health. I applied for support from the Mesoamerican Initiative to be able to rest and take care of my health. The main message of this support: My life is important to other women.

WHRD from Guatemala: The search for justice after the murder of my father, along with my ongoing work defending human rights, led to a breakdown in my physical and mental health. I applied for support from the Mesoamerican Initiative to be able to rest and take care of my health. The main message of this support: My life is important to other women. -

Lisa: The wide, deep networks that JASS is constructing and supporting today serve a double purpose: they foster the power of women's sheer numbers unified around a common agenda, and they provide self-defense and protection. JASS Southern Africa's Heart-Mind-Body initiative addresses the need to focus explicitly on healing from the effects of violence, and we continue to build solidarity among friends and allies and seek new ways to mobilize resources for emergencies, which is especially critical for JASS Mesoamerica.

-

Marusia: While male defenders facing backlash are often supported by their families and networks; women defenders are often blamed for being "bad mothers" or putting their families in danger, which adds to their vulnerability. The Initiative’s work gives women defenders greater clout and reduces their risk through a shield of self-defense and mutual support.

Marusia: While male defenders facing backlash are often supported by their families and networks; women defenders are often blamed for being "bad mothers" or putting their families in danger, which adds to their vulnerability. The Initiative’s work gives women defenders greater clout and reduces their risk through a shield of self-defense and mutual support.

-

-

“Conflict can pose either a danger or an opportunity for positive change.”—Patricia Ardon Alliances, Conflict & Negotiation

Alliances, Conflict and Negotiation is about building agreements and working through conflict inside our groups and within alliances. It is about negotiating relationships with different organizations and political actors who have influence on the issues we care about.

“Coalitions and Alliances often have difficulty managing differences. They sometimes suffer from unrealistic expectations, such as the notion that people who share a common cause will agree on everything. As they evolve, members of coalitions and alliances often realize the importance of not only finding points of agreement, but also agreeing at certain times to disagree.”—Lisa VeneKlasen and Valerie Miller, A New Weave of People, Power & Politics

+ Read MoreAlliances bolster change strategies by bringing together the strength and resources of diverse groups to create a more powerful voice for change. They help people get to the decision-making table. However, alliances can also be complicated and vexing because, like anything that involves human beings, they require building trust, navigating differences, making agreements and on-going attention to relationships. Understanding and negotiating conflict is an essential element of building alliances among diverse actors especially given the risky nature of political organizing in some areas. By its nature, organizing challenges entrenched powers and that generates backlash, which not only creates risk, but can also create tension and division among activists. Conflict among women and within movements is inevitable and must be understood and addressed openly and thoughtfully. JASS bases its approaches on the principle that disparities in power between parties and people in conflict must be addressed as a catalyst for stronger collaboration and alliances for making positive change.

“We really need to understand what it means to build trust. To build trust is a long-term process. There are no shortcuts. There is no formal model to replicate. There are always deep histories in organizations and feminist movements, and those must be acknowledged.”—Atila Roque

Building and sustaining strong, agile political relationships with and among different groups and among women is a sensitive and on-going work which mostly occurs behind-the-scenes. It involves relationship building and fortifying trust, and frequently involves mediating among different groups and individuals, particularly in cases where groups and movements have become embittered through turf battles, pitted against one another or by the overshadowing work of international non-governmental organizations (INGOS).

To maximize the likelihood of success in an alliance, a clear process and commitment to preventing and handling the misunderstandings that produce divisive conflicts must be formed. When conflicts arise, they should be dealt with in a constructive manner. Countries and cultures deal with conflict and conflict resolution in different ways. What may work for someone in Nicaragua may be completely unacceptable for someone in Thailand. Differences within countries exist too, and can become quickly apparent when people from distinct cultures are brought together. Collaboration needs to be based on commonly shared concerns and principles, while taking into account members’ strengths, weaknesses and relative power.

Some of strategies we employ to deal with conflict within alliances include:

- Effective communication that helps resolve disputes and manage differences, and ensures effective negotiation of institutional or agreed-on commitments, interests, and resources.

- Pacts and joint statements of principles to spell out shared principles and responsibilities, and processes and expectations for group interactions. These help members develop systems that facilitate problem-solving and decision-making to avoid misunderstandings. They also avoid false assumptions about group solidarity.

“Understanding power this way challenges the false dichotomy between ‘evil global power holders’ and ‘virtuous social movements.’ Unequal power relations are present in civil society and social movements as well.”—John Gaventa

Tools for Alliances, Conflict and Negotiation

ON-THE-GROUND CONVERSATION…

Patricia Ardon, Marusia Lopez, Joanne Sandler and Laura Carlsen chime in on some of the possibilities and obstacles to building lasting alliances and dealing with conflict.

-

Patricia: To promote the transformations we seek as peoples, and particularly as women in all spheres, we need to strengthen the links and relations between us, support each other and foster trust and solidarity to build our collective power – a power that seeks equality and respect among all forms of life and that nurtures Mother Earth and the planet. Through this trust and connection, we can ensure that the needs and interests of all are contemplated in our processes, helping us prevent the conflicts that we often live in our relationships.

Patricia: To promote the transformations we seek as peoples, and particularly as women in all spheres, we need to strengthen the links and relations between us, support each other and foster trust and solidarity to build our collective power – a power that seeks equality and respect among all forms of life and that nurtures Mother Earth and the planet. Through this trust and connection, we can ensure that the needs and interests of all are contemplated in our processes, helping us prevent the conflicts that we often live in our relationships. -

Joanne: One obstacle is time – democracy takes time, shared leadership takes time, negotiating differences and different interests, perspectives, and understandings takes time.

-

Patricia: The awareness that we have been formed under patriarchy – and therefore that we have internalized many behavioral and thought patterns that we also need to transform – is already a huge step toward being able to approach conflicts in a different way. Why do it from a feminist perspective? Precisely because we believe diversity is a treasure, a way to complement our knowledge, and because we include elements such as tenderness, and care and support for one another. This is not to say that we have no differences. But among ourselves we can develop the reflection and the capacity needed to tackle the obstacles and unravel the knots that have shaped us to act in a certain way, from the intimate to the public sphere. As feminists we do not make a sharp distinction between the public and the private lives of women. The personal is political is at the center of our reflections, and this affects the way in which we can act toward others and among ourselves.

Patricia: The awareness that we have been formed under patriarchy – and therefore that we have internalized many behavioral and thought patterns that we also need to transform – is already a huge step toward being able to approach conflicts in a different way. Why do it from a feminist perspective? Precisely because we believe diversity is a treasure, a way to complement our knowledge, and because we include elements such as tenderness, and care and support for one another. This is not to say that we have no differences. But among ourselves we can develop the reflection and the capacity needed to tackle the obstacles and unravel the knots that have shaped us to act in a certain way, from the intimate to the public sphere. As feminists we do not make a sharp distinction between the public and the private lives of women. The personal is political is at the center of our reflections, and this affects the way in which we can act toward others and among ourselves. -

Marusia: Conflict is inevitable, tensions are inevitable – they’re part of our life as organizations. Conflict can be an opportunity to identify what isn’t working in our organization or in our strategies. It’s an opportunity to recognize how people are being affected by work, by the context of violence. And if we see conflict as an opportunity, we can open the space for building mechanisms so that the conflict can contribute to improve our movements’ work, to improve cohesion between people and activists, and to build a stronger organization.

-

Patricia: Conflict is part of diversity. And it’s part of life and life’s dynamics. And I think it can be an opportunity to put differences on the table, problems that were latent but hadn’t surfaced. It’s also an opportunity to identify elements in common, to identify goals and shared dreams, if we handle it well and if we work on the power dynamics. It’s very difficult to negotiate when there are big power asymmetries. I also think it’s a process, not an isolated action, that implies identifying needs, our own interests and the interests of others, and that truly seeks to address common concerns and problems, understanding that they’re interdependent.

Patricia: Conflict is part of diversity. And it’s part of life and life’s dynamics. And I think it can be an opportunity to put differences on the table, problems that were latent but hadn’t surfaced. It’s also an opportunity to identify elements in common, to identify goals and shared dreams, if we handle it well and if we work on the power dynamics. It’s very difficult to negotiate when there are big power asymmetries. I also think it’s a process, not an isolated action, that implies identifying needs, our own interests and the interests of others, and that truly seeks to address common concerns and problems, understanding that they’re interdependent. -

Laura: It’s really important to nurture alliances. You can have a magic moment of collaboration on a particular action or campaign, but if you don’t put the effort into follow-up, that collaboration will not grow into a lasting alliance that broadens your base and strengthens your movement.

-

Patricia: Lasting alliances are those that are built on long-term common objectives. Although we may not have those objectives entirely clear at this time, we do agree that we can change the world, change the situation of injustice and inequality in which we live. But there can be many types of alliances. An example is an explicit alliance in which – although we do not coincide in everything – we have a common short-term goal, such as an alliance to develop a concrete activity where we can complement each other. But from the beginning of any alliance, it is important to clarify what the strength of each party is, what resources we have, and how decisions will be made.

Patricia: Lasting alliances are those that are built on long-term common objectives. Although we may not have those objectives entirely clear at this time, we do agree that we can change the world, change the situation of injustice and inequality in which we live. But there can be many types of alliances. An example is an explicit alliance in which – although we do not coincide in everything – we have a common short-term goal, such as an alliance to develop a concrete activity where we can complement each other. But from the beginning of any alliance, it is important to clarify what the strength of each party is, what resources we have, and how decisions will be made.

ON-THE-GROUND CONVERSATION…

Listen to Shereen Essof, Kwangu Tembo Makhuwira, Tiwonge Gondwe, Dorica Maguba, Amina Doherty, Lisa VeneKlasen, Sibongile Singini and Daysi Flores reflect on how to mobilize our collective power.